By Hannah Johnston, Library Volunteer

While today many of us would relegate monsters to fantasy books and Halloween decor, to people in seventeenth-century England, monsters were very real. Fantastical beasts were thought to inhabit the far corners of the world, but perhaps more astonishing were the “beasts” born right at home.[1] Narratives of “monstrous births” could be found in pamphlets, balladry, and even medical books, and the infants in question ranged in these texts from frightening spectacles to prodigal symbols. Of course, many of the babies deemed “monstrous” were not, in fact, monsters. For every “actual” monster – serpents, flying infants, rabbits birthed by a human woman – there was a birth which in the modern era could be explained by numerous common as well as rare conditions.[2]

Nevertheless, this fascination with abnormal births can tell us quite a bit about the many ways early modern people conceptualized and dealt with bodies that defied categorization; among these was the child’s relationship with its mother. The placing of blame on mothers for their own monstrous births reflects a frustration with the lack of understanding of the female body, as well as an interest in encouraging “proper” behavior in women.

The False Lover Rewarded, 1760? Huntington Library 289786, EBBA 32528. Licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Most people in the 17th century would learn about a monstrous birth from cheap print sources such as pamphlets and broadside ballads. Broadside ballads in particular were incredibly popular, affordable, and widely available to the public. Often sold by female “hawkers” on the street, broadside ballads could be bought by just about anyone and were written to entertain as well as inform.[3] While some ballads were based on true (if exaggerated) events, many were entirely works of fiction. Ballads overall were more concerned with entertainment and moral policing than exploring the functional causes of abnormal births. Sensationalist in nature, they often focused on the spectacle of a single birth, and were often framed as a divine punishment for the mother’s sins or flaws.

The Lamenting Lady, 1620? Magdalene College – Pepys Ballads 1.44-45 EBBA 20210. Licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

While many ballads focused on the physical aspects of infants’ bodies, the way some births occurred were seen as monstrous in and of themselves. “The Lamenting Lady,” published circa 1620, was one such ballad, focusing on the story of a “[lady] of degree” who, despite having beauty and a comfortable lifestyle, could not bear a child.[4] One day, a “poore woman” came to her door with her two children to beg for money. The woman could not fathom why “Beggers [sic] have what Ladies want,” and became irate with the beggar, asserting that she had had her children as a result of being unfaithful to her husband.[5] To punish the woman for her jealous behavior, the beggar woman promptly cursed her:

And for these children two of mine

heaven send thee such a number

At once, as dayes be in the yeare,

to make the world to wonder.

For I as true a wife have beene,

unto my husbands love:

As any Lady on the earth,

unto her Lord can prove.[6]

Because of her unkindness towards the poor woman, the wealthy woman was cursed to give birth to three-hundred and sixty-five children in succession.[7] “The Lamenting Lady” was, of course, a fictional account. However, this chastising tone is common to even the true (or at least more believable) accounts of monstrous births. Balladry, while interested in the causes of monstrous births, was centered on using them both to entertain and to discourage the behavior that was thought to cause them.

While pamphlets and ballads were focused mostly on the spectacle aspect of monstrous births, many books, in particular medical or midwifery manuals, sought to explore their cause. Aristotle’s Masterpiece was one of several works to try to answer the pressing question of where monstrosity came from. An amalgam of earlier works by various authors, the book was first published in 1684 and remained widely popular among curious readers through the early 20th century.[8] The author (or compiler) of the work is unknown, having used “Aristotle” as a pseudonym, likely to invoke authority.[9]

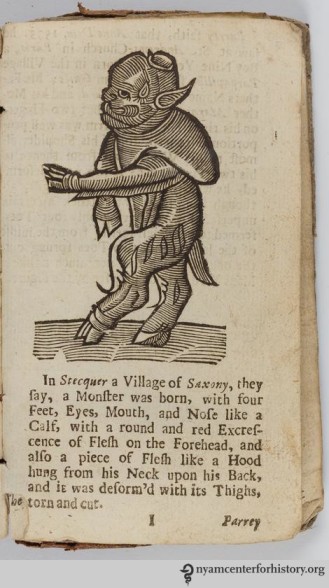

Example of a “monster” in Aristotle’s Masterpiece, or The Secrets of Generation displayed in all the parts thereof… London, 1684. NYAM Collection.

Among many topics pertaining to sex, pregnancy, and childbirth, included in the Masterpiece was a chapter on the causes of “monstrous conceptions.”[10] Many people believed that a monstrous conception could be caused by a birth ill-timed with the stars, or a flaw in the “seed” of either parent.[11] The Masterpiece, while acknowledging these to be true, noted another important factor in an abnormal birth – the thoughts of the parents, particularly of the mother.[12] Already a popular concept by the Masterpiece’s publication, the theory of maternal imagination stated that the pregnant mother’s feelings, experiences, and thoughts could impact the development of her child.[13] While in line with the representations of monstrous births in balladry, the theory of maternal imagination sought to explain how the mother’s actions could physically alter her unborn child’s body. In particular, an infant could become “monstrous” if its mother were to wish for, think about, or look upon a thing or person to excess. The theory of maternal imagination would have supported the interpretations of monstrous births seen in cheap print, where mothers’ sins marked the bodies of their children.

Together, the representations of monstrosity in cheap print and in books suggest an interest in finding someone to blame for the curiosity, fear, and occasional tragedy associated with abnormal births. Seventeenth-century English print constructed a connection between the actions of mothers and the bodies of children that served to entertain, inspire fear, and encourage moral behavior in mothers-to-be.

References

[1] Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park, Wonders and the Order of Nature (New York, NY: Zone Books, 1998), pp 173–214.

[2] For flying: “The False Lover Rewarded” (London, UK: 1760), EBBA; For rabbits: See the well-known case of Mary Toft, who (falsely) claimed to have given birth to rabbits. Glennda Leslie, “Cheat and Impostor: Debate Following the Case of the Rabbit Breeder,” The Eighteenth Century 27, no. 3 (1986): 269–86.

[3] Patricia Fumerton and Anita Guerrini, ed. Ballads and Broadsides in Britain, 1500–1800 (Oxon, UK and New York, NY: Routledge, 2010).

[4] “The Lamenting Lady, Who for the wrongs done to her by a poore woman, for hauing two children at one burthen, was by the hand of God most strangely punished, by sending her as many children at one birth, as there are daies in the yeare, in remembrance whereof, there is now a monument builded in the Citty of Lowdon, as many English men now liuing in Lowdon, can truely testifie the same and hath seene it,” 1620? EBBA.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Mary Fissell, “Hairy Women and Naked Truths: Gender and the Politics of Knowledge in ‘Aristotle’s Masterpiece,’” The William and Mary Quarterly 60 No 1, “Sexuality in Early America,” Jan 2003, pp 43–74; Pseudo Aristotele, and John How, Aristotle’s Masterpiece, Or The Secrets of Generation displayed in all the parts thereof (London, England: 1684).

[9] Fissell 47.

[10] Aristotle’s Masterpiece 51.

[11] Ibid 52.

[12] Ibid 51.

[13] Daston & Park 192.

Pingback: John Locke’s Copy of The Secret Miracles of Nature and the NYAM Library | Books, Health and History

Pingback: Adieu Halloween: The True Meaning of Monsters

Pingback: Disability in Shakespeare's England - Cassidy Cash