By Anthony Murisco, Public Engagement Librarian

Despite the name, Pet Milk isn’t for your furry friends! Formerly the Helvetia Milk Condensing Company, the company broke ground in Highland, Illinois in 1885. For years, they would be the standard for canned and condensed milk. If their own words are to be believed, they may have even given whole milk a run for their money.

Pet Milk’s messaging made them seem like the All-American brand of milk. They were there when future President Teddy Roosevelt fought alongside other soldiers in the Spanish-American War. The canned beverage was available for our troops overseas during both great wars. What was more American than providing nourishment and daily vitamins for these heroes? When they returned, seeing the brand name in their cupboard or on the store shelves could trigger strength and loyalty. Milk was the drink of choice with the average American’s dinner. It’s no wonder that the brand had garnered such popularity!

The 1932 Pet Cookbook comes after two huge American events; the end of World War I and the Great Depression. In their introduction, Pet Milk boasts of “a valuable new quality,” the addition of vitamin D. An essential vitamin, it prevents rickets in children. Despite this priceless addition, the company reminds readers—in big font—that; “the cost of Pet Milk has not been increased because of the extra sunshine vitamin D it now contains.” As Americans struggle amidst an economic downfall, the values of an American company remain true to their customers.

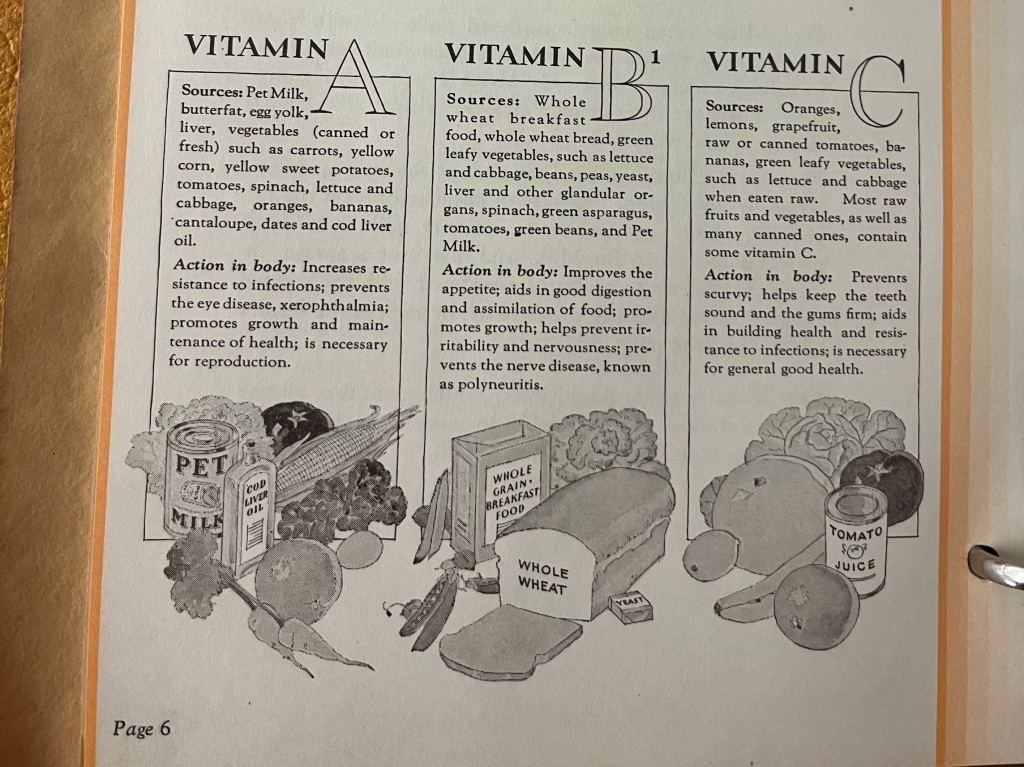

The cookbook is a masterpiece of marketing and nutrition. Each recipe inside specifically calls for Pet Milk. This was done not only because they put out the recipe book, they assure you, but because their product is unlike other kinds of milk, including “ordinary whole” milk. With milk being “one of the most important of all our items of food,” or even “the most nearly perfect food,” you want to be sure you are choosing the right kind! The vitamins contained in a serving of Pet Milk span the alphabet. This isn’t the case with any other milk, they claimed. The company speaks of the importance of “irradiated” milk: using ultra-violet rays to provide an extra dose of Vitamin D.

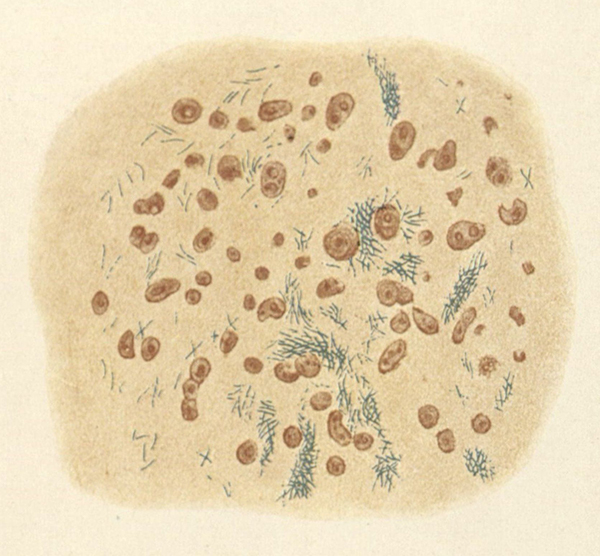

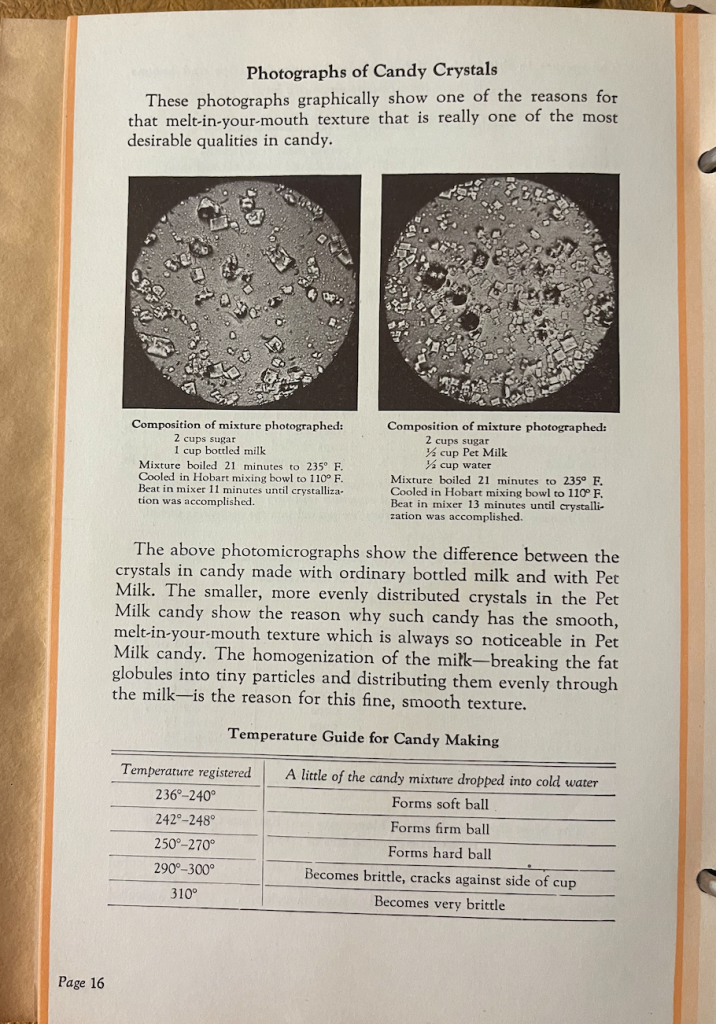

The company claims that typical whole cow’s milk could vary in taste, while Pet Milk’s provides uniform taste. For that reason, they believe it should be the standard to use in recipes. Don’t believe their words? Pet Milk boasts of the “melt-in-your-mouth texture” that stems from making candy with their product and tells you why. The photomicrograph on the left shows fewer numbers and larger crystals when making candy with regular milk. The image on the right shows what happens when you make candy with Pet Milk. Smaller crystals, and more of them, results in an eruption of flavor for your taste buds. The company was so confident in their science that it appeared almost verbatim two years later in a holiday- themed recipe book.

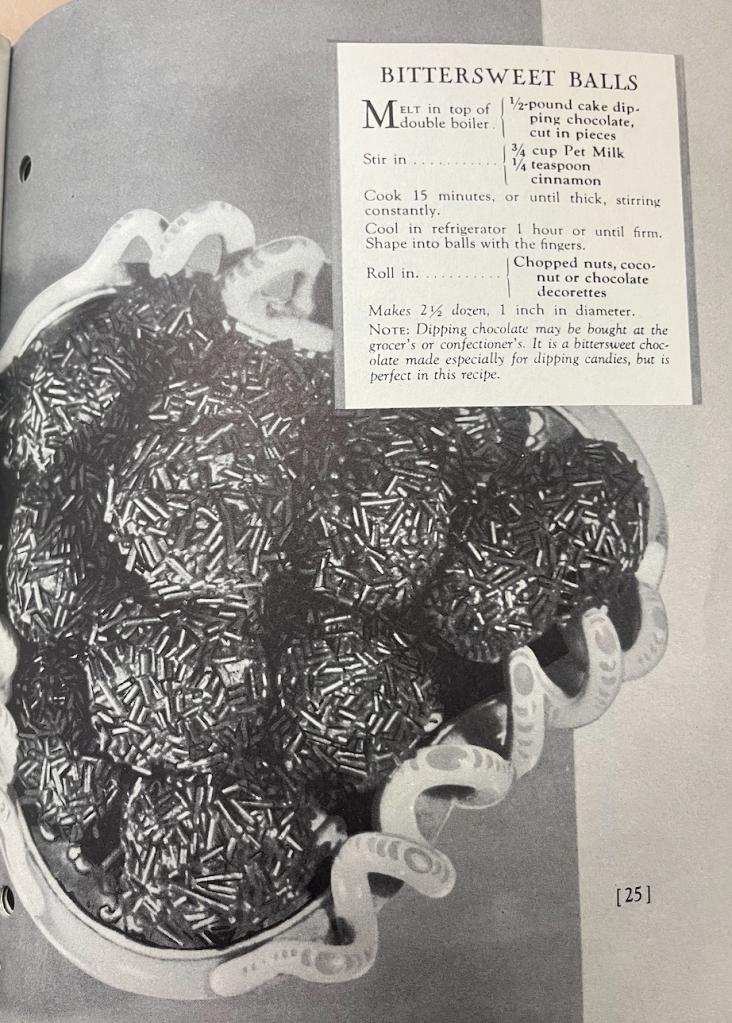

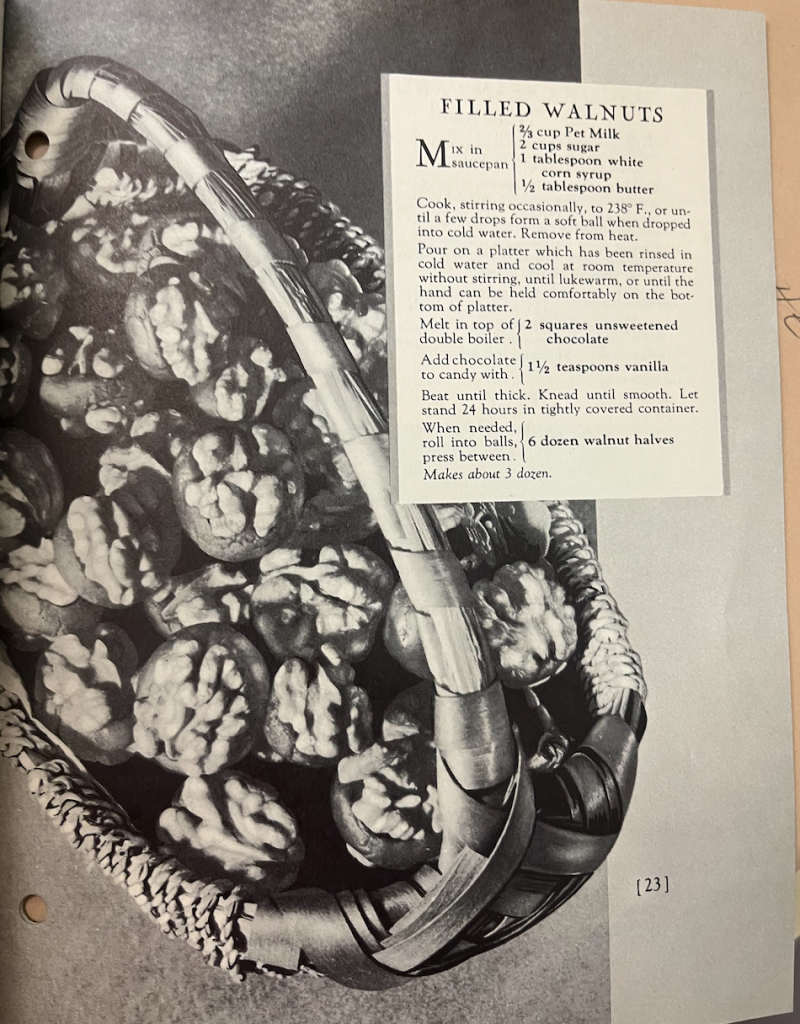

Candies may be one of the most “desirable” gifts for your “holiday entertaining.” It’s not just for the younger ones! “Sweet-toothed” adults also appreciate getting treats during the holiday season. Brand loyalty is important here, Pet says. Your family will taste the difference when you make your holiday sweets with Pet Milk. And of course, you’re providing them with all the added nutrients you’ve come to expect!

Any of these recipes featured can be replicated today. Pet Milk may not have the panache it once had but it is still available. Other brands of condensed milk can also be substituted. We cannot confirm or deny whether the lack of “flavor crystals” will impact the taste. You might want to make a couple batches just in case….

If you can somehow manage to save some of these delicious candies for gifting, you’ll want to dress them up a bit. Pet Milk provides some suggestions for how you’ll want to give these out. Head over to your local “ten-cent store” for various containers to put them in. You can get creative here. For an added look, “flowers” made of cellophane-wrapped candies can be draped on top.

From all of us at the New York Academy of Medicine Library, we wish you a happy and healthy holiday season. Seasons’ eatings!

References:

“Our History,” PET Milk, https://www.petmilk.com/history, accessed December 15, 2023.

Pet Milk Company. Candies. St. Louis, Mo.: Pet Milk Co., 1934.

Pet Milk Company. The Pet cookbook: 700 cost-saving recipes for better food / tested and approved by Good Housekeeping Institute. St. Louis, Mo.: Pet Milk Co., 1932.