Kriota Willberg, the author of today’s guest post, explores the intersection of body sciences with creative practice through drawing, writing, performance, and needlework. She is offering the workshop “Visualizing and Drawing Anatomy” beginning June 6 at the Academy. Register online.

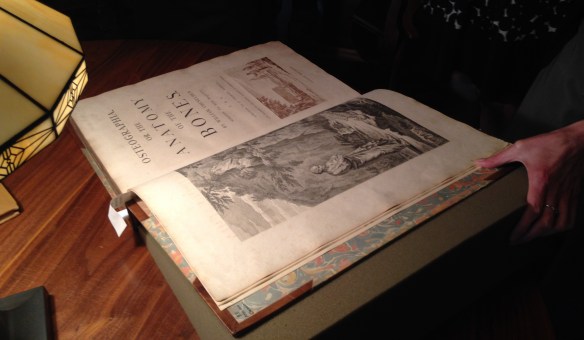

Cheselden’s Osteographia, 1733, opened to the title page and frontispiece.

Different Disciplines, Same Body

I teach musculoskeletal anatomy to artists, dancers, and massage therapists. In my classes the students study the same raw material, and the set of skills each group acquires can be roughly organized around three distinct areas: representation of the body, kinesiology (the study of movement), and palpation (feeling the body).

As an anatomy teacher I am constantly on the prowl for images of the body that visually reinforce the information my students are learning. The Internet has become my most utilized source for visual teaching tools. It is full of anatomy virtual galleries, e-books, and apps. 3D media make it ever easier to understand muscle layering, attachment sites, fiber direction, and more.

In spite of the overwhelming volume of quality online cutting-edge anatomical imagery, I find myself drawn to historical 2D printed representations of the body and its components, once the cutting-edge educational technology of their respective centuries. Their precision, character, size, and even smell enhance my engagement with anatomical study. Many of these images emphasize the same principles as the apps replacing them centuries later.

The Essential Structure Of The Body

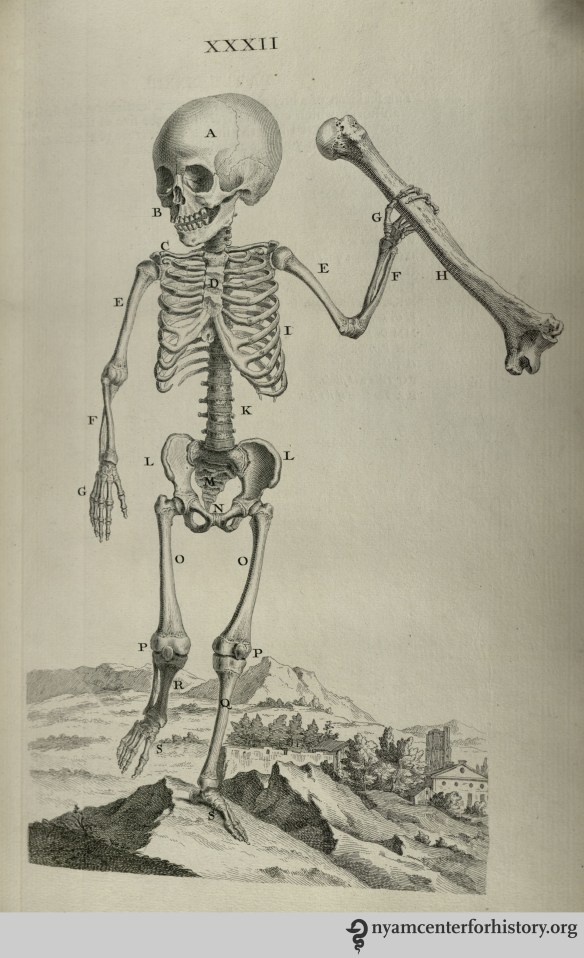

Different artists prefer different methods of rendering bodies in sketches. One method is to organize the body by its masses, outlining its surface to depict its bulk. Another method is to draw a stick figure, organizing body volume around inner scaffolding.

And what is a skeleton but an elaborate stick figure? William Cheselden’s Osteographia (1733) presents elegant representations of human and animal skeletons in action. These images remind us that bones are rigid and their joints are shaped to perform very specific actions. The cumulative position of the bones and joints gives the figure motion. In Cheselden’s world of skeletons, dogs and cats fight, a bird eats a fish, a man kneels in prayer, and a child holds up an adult’s humerus (upper arm bone) to give us a sense of scale while creating a rather creepy theatrical moment.

Muscle Layering

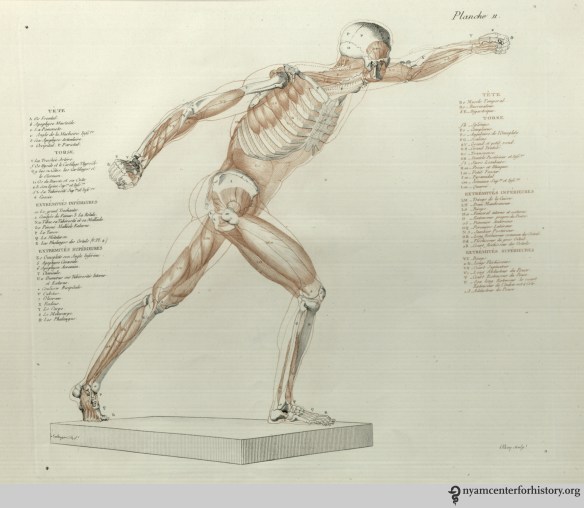

3D apps and other imaging programs facilitate the exploration of the body’s depth. One of the challenges of artists and massage therapists studying anatomy is transitioning information from the 2D image of the page into the 3D body of a sculpture or patient.

Salvage’s Anatomie du gladiateur combattant: applicable aux beaux artes… (1812) is a 2D examination of the 3D Borghese Gladiator. Salvage, an artist and military doctor, dissected cadavers and positioned them to mimic the action depicted in the statue. His highly detailed images depict muscle layering of a body in motion. The viewer can examine many layers of the anatomized body in action from multiple directions, rendered in exquisite detail. Salvage retains the outline of the body in its pose to keep the viewer oriented as he works from superficial to deeper structures.

Bernhard Siegried Albinus worked with artist Jan Wandelaar to publish Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani (1749). Over their 20-year collaboration, they devised new methods for rendering the dissected body more accurately. The finely detailed illustrations and large size of the book invite the reader to scrutinize the dissected layers of the body in all their detail. Although there is no superficial body outline, the cadaver’s consistent position helps to keep the reader oriented. On the other hand, cherubs and a rhinoceros in the backgrounds are incredibly distracting!

Fiber Direction

Familiarity with a muscle’s fiber direction can make it easier to palpate and can indicate the muscle’s line of pull (direction of action).

The images of Jacopo Berengario da Carpi’s Anatomia Carpi Isagoge breves, perlucide ac uberime, in anatomiam humani corporis… (1535) powerfully emphasize the fiber direction of the muscles of the waist. This picture in particular radiates the significance of our “core muscles.” Here, the external oblique muscles have been peeled away to show the lines of the internal obliques running from low lateral to high medial attachments. The continuance of this line is indicated in the central area of the abdomen. It perfectly illustrates the muscle’s direction of pull on its flattened tendon inserting at the midline of the trunk.

The Internal Body Interacting with the External World

One of the most important lessons of anatomy is that it is always with us. Gluteus maximus and quadriceps muscles climb the stairs when the elevator is broken. Trapezius burns with the effort of carrying a heavy shoulder bag. Heck, that drumstick you had for lunch was a chicken’s gastrocnemius (calf) muscle.

Anatomists from Albinus to Vesalius depict the anatomized body in a non-clinical environment. One of my favorites is Adriaan van de Spiegel and Giulio Casseri’s De humani corporis fabrica libri decem (1627). In this book, dissected cadavers are depicted out of doors and clearly having a good time. They demurely hold their skin or superficial musculature aside to reveal deeper structures. Some of them are downright flirtatious, reminding us that these anatomized bodies are and were people.

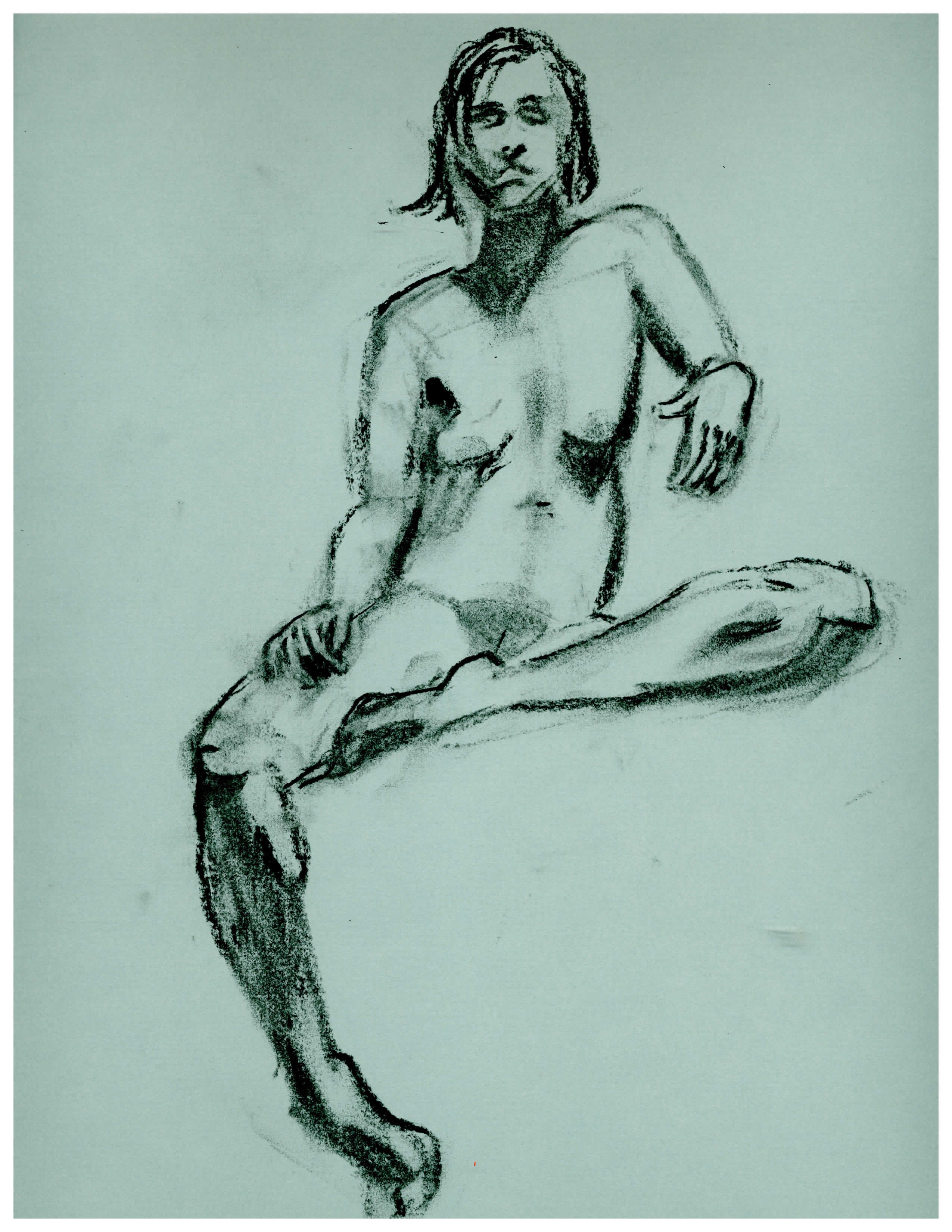

Kriota Willberg’s self portrait. Courtesy of the artist.

I am so enamored of van de Spiegel and Casseri that I recreated page 24 of their book as a self-portrait. After my abdominal surgery, the image of this cadaver revealing his trunk musculature resonated with me. In my portrait I assume the same pose, but if you look closely you will see stitch marks tracing up my midline. I situate myself in a “field” of women performing a Pilates exercise that challenges abdominal musculature. And of course, I drew it in Photoshop.