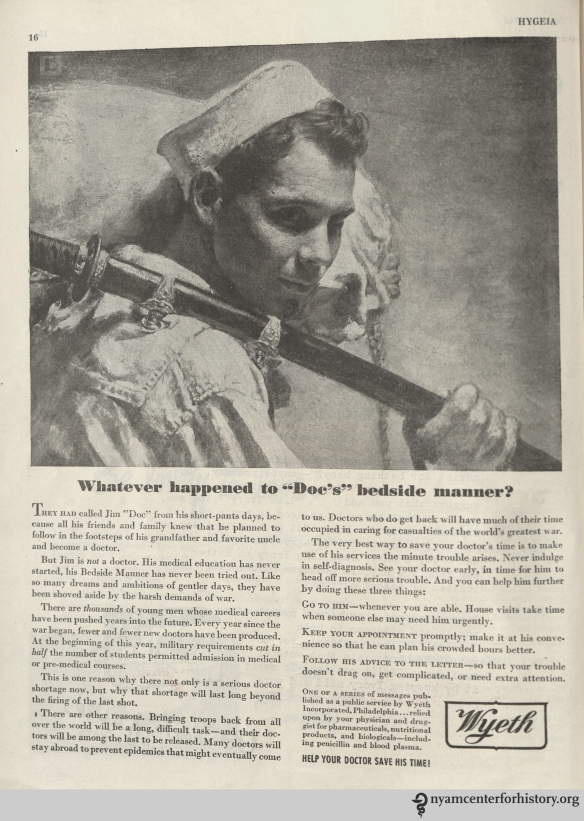

By Johanna Goldberg, Information Services Librarian

This is part of an intermittent series of blogs featuring advertisements from medical journals. You can find the entire series here.

“How did you learn to be a dentist? Did you go to a college?”

“I went along with a fellow who came to the mine once. My mother sent me. We used to go from one camp to another. I sharpened his excavators for him, and put up his notices in the towns–stuck them up in the post-offices and on the doors of the Odd Fellows’ halls. He had a wagon.”

“But didn’t you never go to a college?”

“Huh? What? College? No, I never went. I learned from the fellow.”

Trina rolled down her sleeves. She was a little paler than usual. She fastened the buttons into the cuffs and said:

“But do you know you can’t practise unless you’re graduated from a college? You haven’t the right to call yourself, ‘doctor.'”1

In Frank Norris’ 1899 novel McTeague: A Story of San Francisco—better known for its depiction of greed than the professionalization of dentistry—the title character loses his 12-year-old dental practice after California requires practitioners to hold a degree in the field. The timing couldn’t be worse for McTeague: he’d only just fulfilled a long-held dream, obtaining and hanging an enormous golden tooth outside his dental parlor.

McTeague’s fictionalized struggle was based in reality: until the mid to late 1800s, dentistry in the United States was not a regulated profession. Alabama became the first state to regulate dentists in 1841, and other states followed suit through the end of the century.2 In 1885, California passed a law requiring practicing dentists to register with a board, which could call up registrants for examination. Diplomas from a licensed dentistry school—the University of California College of Dentistry opened in San Francisco in 1882—also qualified registered dentists to practice. In 1901, a new law made practicing dentistry in California even more restrictive, part of a nationwide move to tighter regulation.3,4 In the novel as it would have been in real life, McTeague’s practice was toast.

Advertisements in dental journals from the era depict the trend toward professionalization, along with other technological advances. In 1840, the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery opened its doors as the first dental school in the world; by 1895, it had some local competition, including the Dental Department of the Baltimore Medical College.4 This school advertised heavily in journals like the American Journal of Dental Science.

Ad for the Dental Department of the Baltimore Medical College in the American Journal of Dental Science, vol. 33, no. 10, February 1900.

Intriguingly, not only dental schools advertised in dentistry journals: The February 1901 volume of Dental Hints includes an ad encouraging dentists to take up a correspondence course in optometry, “on account of the intimate relationship between the eye and the teeth.” Huh?

Advertisement for the Philadelphia Optical College in Dental Hints, vol. 3, no. 2, February 1901.

Dental journal advertisements also reflect anesthetic advances. William Morton, a dentist, performed the first public demonstration of ether as a surgical anesthetic in 1846.2 A similar demonstration of nitrous oxide in 1845 did not go so well: dentist Horace Wells extracted a tooth before administering the proper dosage, and the patient cried out in pain. The drug was tabled for about 20 years; by 1869, it was commonly used either on its own or in conjunction with ether for dental procedures.2,5 Dental surgeries held less risk than other medical procedures, as they were commonly performed either in the patient’s or dentist’s home, locations less teeming with deadly microbes than operating theaters. After advances in antiseptic surgery by people like Joseph Lister, dental surgery became even safer—and Dr. Joseph Lawrence named an antiseptic mouthwash in his honor.5,6

Codman & Shurtleff’s Inhaler for Gas or Ether advertisement in Dental and Oral Science Magazine, vol. 1, no. 2, May 1878.

Listerine advertisement in the American Journal of Dental Science, vol. 33, no. 10, February 1900.

Local anesthetics also entered the market around the turn of the century. Some, like Mylocal, contained cocaine—though in the case of Mylocal, that cocaine was to be added by the practitioner prior to use. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the amount of cocaine used in local anesthetics was often poorly controlled, with sometimes dire results.5 Another local anesthetic, Eureka, proudly advertised that it “[avoids] that most dangerous drug that is known to the profession as COCAINE.” A third, Wilson’s Local Anaesthetic, notes that it is “non-secret and positively guaranteed.” Unfortunately, its ads don’t state what these non-secret ingredients are.

Advertisement for Mylocal anaesthetic in the American Journal of Dental Science, vol. 39, no. 1, January 1908.

Advertisement for Eureka Local Anaesthetic in Dental Hints, vol. 3, no. 2, February 1901.

Advertisement for Wilson’s Local Anesthetic in Dental Clippings, vol. 3, no. 6, April 1901.

Other turn-of-the-century advances include the development of tube toothpaste in the 1880s (previously, toothpaste had only been available in powdered form); awareness of microbial causes of tooth decay, leading to the promotion of flossing and brushing in the 1890s; and the use of gold foil as a cavity filling in the 1850s.2 The ads below reflect these advances and others, and were selected to show the relatively pain-free side of dentistry.

R. S. Williams Toothbrushes advertisement in Dental and Oral Science Magazine, vol. 1, no. 2, May 1878.

Ney’s Gold Plates advertisement in the American Journal of Dental Science, vol. 33, no. 1, May 1899.

Dental Floss Silk advertisement in advertisements in the American Journal of Dental Science, vol. 33, no. 10, February 1900.

McConnell Dental Chair advertisement in Dental Hints, vol. 3, no. 4, April 1901.

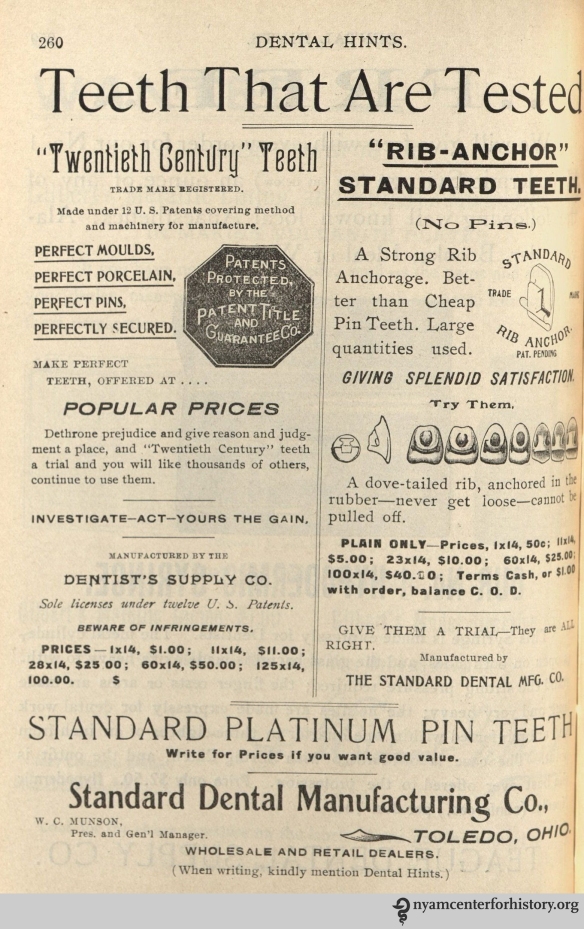

Standard Dental Manufacturing Co. advertisement in Dental Hints, vol. 3, no. 5, May 1901.

Dentacura toothpaste advertisement in Dental Hints, vol. 3, no. 11, November 1901.

Munson’s Standard Teeth advertisement in Dental Hints, vol. 3, no. 12, December 1901.

Prophylactic Toothbrush advertisement in Dental Summary, vol. 22, no. 7, July 1902.

Antikamnia and Odontoline advertisements in advertisements in the American Journal of Dental Science, vol. 39, no. 4, April 1908.

Baker Coat Co. and Keeton Gold advertisements in the American Journal of Dental Science, vol. 39, no. 4, April 1908.

Bowl Spittoon advertisement in the American Journal of Dental Science, vol. 39, no. 4, April 1908.

References

1. Norris F. McTeague.; 1899. Available at: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/165/165-h/165-h.htm. Accessed May 9, 2016.

2. History of Dentistry Timeline. Available at: http://www.ada.org/en/about-the-ada/ada-history-and-presidents-of-the-ada/ada-history-of-dentistry-timeline. Accessed May 9, 2016.

3. Newkirk G. California. In: Koch CRE, ed. History of dental surgery: Dental laws and legislation, dental societies and dental jurisprudence, Vol. III. Fort Wayne, Ind.: National art publishing Company; 1910:755–756. Available at: https://books.google.com/books?id=9iE-AQAAMAAJ&pgis=1. Accessed May 9, 2016.

4. Schulein TM. A chronology of dental education in the United States. J Hist Dent. 2004;52(3):97–108.

5. Enever G. History of dental anaesthesia. In: Shaw I, Kumar C, Dodds C, eds. Oxford Textbook of Anaesthesia for Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/med/9780199564217.001.0001.

6. From Surgery Antiseptic to Modern Mouthwash | LISTERINE®. Available at: http://www.listerine.com/about. Accessed May 10, 2016.