by Anthony Murisco, Public Engagement Librarian

On February 14th we observe Valentine’s Day, a day that has come to signify and celebrate all the love in our lives. Some may take loved ones out to dinner, some buy gifts, and some may even do a grand gesture, like ask for their lover’s hand in marriage.

St. Valentine was a 3rd-century Roman priest, maybe even a bishop, who ministered to those persecuted by the church. It was believed that he delivered messages to lovers who had been torn apart. The Feast of St. Valentine was introduced in the late 5th century to commemorate his decapitation, on February 14th. While his end doesn’t sound romantic, we can see how future lovers had come to admire the man.

Back in 1853, the New York Times first questioned how the modern Valentine’s Day came to be. They concluded that it was an “antiquarian problem” that would likely “never be solved.” They must’ve realized how funny that sounds in the age of information, so they revisited this inquiry in 2017 and once again in 2023. Two theories were brought forth to go along with the holiday’s namesake.

The first one credits Geoffrey Chaucer. In his 14th-century poem, “Parlement of Foules,” Chaucer namechecks “St. Valentine’s Day” and speaks of how on this special day, a bird will choose their mate. That sounds a little like the holiday that we celebrate. His words eventually trickled into the English lexicon, as many whom Chaucer inspired began to note the holiday.

The alternative look further back to the ancient Roman fertility festival of Lupercalia. This is where men and women paired off. Well, with wine free flowing, the occasion tended to get a bit wilder. The Christian church came and cleaned that up, but it remained a coupling ritual.

From these traditions we can see the rough sketches of the holiday we’ve come to know. By the time the New York Times originally investigated, it had already become a “greeting card” holiday. The writer mentions the “symbols and paraphernalia of Cupids, hearts, and love letters,” associated with the day. What would they make of the holiday aisles and celebrations of our era?

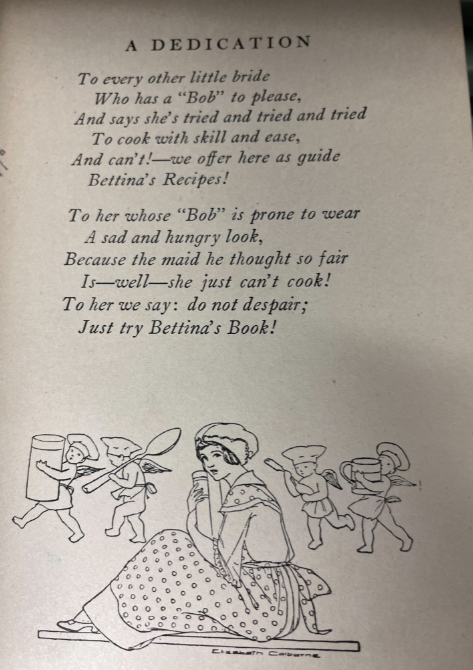

We have previously looked inside the narrative homemaker books starring “Bettina.” In A Thousand Ways to Please a Husband, she juggles the first year of marriage to “Bob.” Later volumes would see her raising a family, and even teaching her own daughter how she can begin to train for her own home one day. Books like these were often given as gifts to brides or brides-to-be. The dedication page offers hope for those who may not feel like they can handle this society-given duty.

The narrative, illustrations, and the recipes that ended every chapter make the book charming. As stated in the previous blogpost, the gender politics within have not aged well. Bettina doesn’t seem to ever catch a break! Left home alone, she’s the one making sure the house continues to function. This is even before the kids, Robin and Sue, come into the picture.

In …Husband we get a look at the couple’s first Valentine’s Day as husband and wife. Flowers seem to be the only item that Bob gave–though, to be fair, they are called “lovely” and “brilliant.” Bettina apologizes for not making more of a big deal, as if it was only on her to do so!

She tells how she had spent most of the afternoon at a luncheon with friends. When she mentions the décor, Bob seems to mock all the hearts and red by calling it “Valentine’s Day with a vengeance.” She assures him that it was “lovely,” as she serves up the steak dinner that she had just thrown together.

Years later, in A Thousand Ways to Please a Family, we join Bettina at the Valentine’s Day luncheon she is cohosting with her friend, Alice. The guests are taken to Alice’s guest room. No talk of romance is present: she talks of the furniture, the furnishings, and the paint which covers “a multitude of sins.” As the two hosts move to the kitchen, Alice laments what once was. She asks, “What is Valentine’s Day in our lives, now?” They eventually move on to their menu of heart-shaped foods.

We want to bring back those lost feelings of Valentine’s Day! In honor of the rather unromantic circumstances our female characters found themselves in, this year we are providing a gift; four recommendations from a genre perfect for Valentine’s Day, romance! Romance as a genre has roots back to ancient Rome (again!) while the first romance book, Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded, was published in 1740 by English author Samuel Richardson.

The softcover paperbacks that we’ve come to associate with romance novels came out of the late 60’s/early 70’s. Almost instantly, they were a hit amongst female readers. Despite this, derogatory labels and preconceived notions have kept romance books hidden away. They were treated almost like scarlet letters. After years of consistently making up a large part of book sales, romance novels and authors have only now begun to command the respect they deserve. Romance often provides their readers with some of the most diversity featured on a bookshelf.

So, this one is for Bettina, Alice, and anyone else on this Valentine’s Day. We present a librarian’s recommendation for some romance novels. This trio of books have all come out, in the United States, in the last year or two and all of them feature main characters or romantic partners who are medical professionals. The link will direct you to WorldCat but should be available at your local public library!

Anatomy of A Meet Cute by Addie Woolridge. As if being the new hire isn’t hard enough, Sam somehow manages to insult one of her fellow doctors. Great—this is just what she needs. In order to get the board to agree to her new proposal, she’s going to have to make some new allies quick. Maybe she can apologize to Grant and get him on board. And maybe they’ll find out they have more in common than they think….

The Plus One by Mazey Eddings. Indira has just moved back in with her brother after she caught her boyfriend cheating on her. Her brother is about to get married and his best friend Jude is also staying with him. Jude has spent the last few years as a doctor traveling the world tending to humanitarian crises. Despite their mutual love, Indira and Jude have always hated each other. Somehow their forced wedding attendance, as a fake couple, has them rethinking some of these strong feelings.

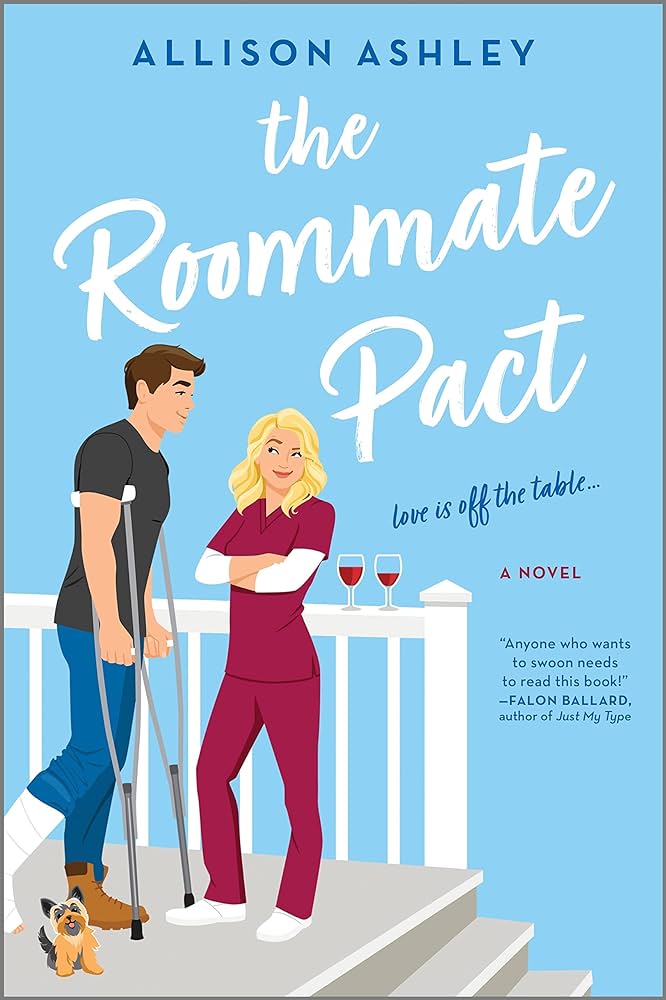

The Roommate Pact by Allison Ashley. Claire and Graham are too busy for romantic relationships. That’s why they get each other. One night they make a drunken pact to get married and take care of one another if they are both single at forty. When Graham injures himself, the two realize it’s more than Claire’s expertise as an ER nurse that he needs.

References:

“About the Romance Genre.” Romance Writers of America, http://www.rwa.org/Online/Education/About_Romance_Fiction/Online/Romance_Genre/About_Romance_Genre.aspx?hkey=dc7b967d-d1eb-4101-bb3f-a6cc936b5219#Romance_Reader. Accessed 14 Feb. 2024.

Goldberg, Johanna. “A Thousand Ways to Please.” Books, Health and History, 14 Apr. 2016, nyamcenterforhistory.org/2016/04/14/a-thousand-ways-to-please/. Accessed 14 Feb. 2024.

Sommerlad, Joe. “Who Was St Valentine and Why Is He Associated with Love?” The Independent, 14 Feb. 2024, http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/love-sex/story-of-st-valentine-history-patron-saint-b2495966.html. Accessed 14 Feb. 2024.

Stack, Liam. “The Origins of Valentine’s Day: Was It a Roman Party or to Celebrate an Execution?” The New York Times, 14 Feb. 2023, http://www.nytimes.com/article/valentines-day-facts-history.html. Accessed 14 Feb. 2024.

Weaver, Louise Bennett, and Helen Cowles Le Cron. A Thousand Ways to Please a Family with Bettina’s Best Recipes. N.Y., A.L. Burt company, 1922.

Weaver, Louise Bennett, and Helen Cowles Le Cron. A Thousand Ways to Please a Husband with Bettina’s Best Recipes. New York, Britton Publishing Company, 1917.