By Arlene Shaner, Historical Collections Librarian

An earlier blog post of ours highlighted the work of Gladys McHugh, a medical illustrator who used transparent acetate sheets to create her illustrations for The Human Eye in Anatomical Transparencies and The Human Ear in Anatomical Transparencies. McHugh studied medical illustration with Max Brödel at Johns Hopkins in the Department of Art as Applied to Medicine, one of a significant number of women who trained with him to become well-known medical illustrators.

Annette Smith Burgess (1899-1962), was another of Brödel’s students. Burgess studied with Brödel for three years starting in 1923 before becoming the first ophthalmic illustrator for the Wilmer Eye Institute, a position she held for the next 35 years, until her retirement in 1961. Beginning in 1946 (and more officially in 1948), she took on an additional role as an instructor in the Art as Applied to Medicine program.

Portrait of Annette Smith Burgess.[1]

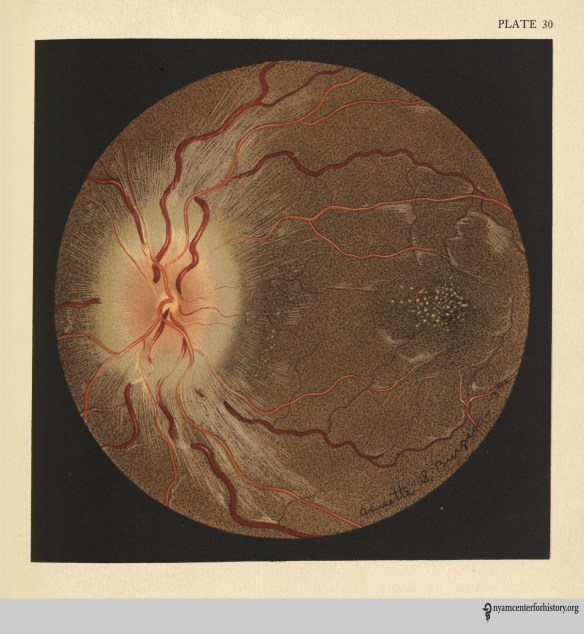

“Papillo-retinitis, with Papilledema, Toxic and Mechanical” (plate 30), from Atlas Fundus Oculi (1934).

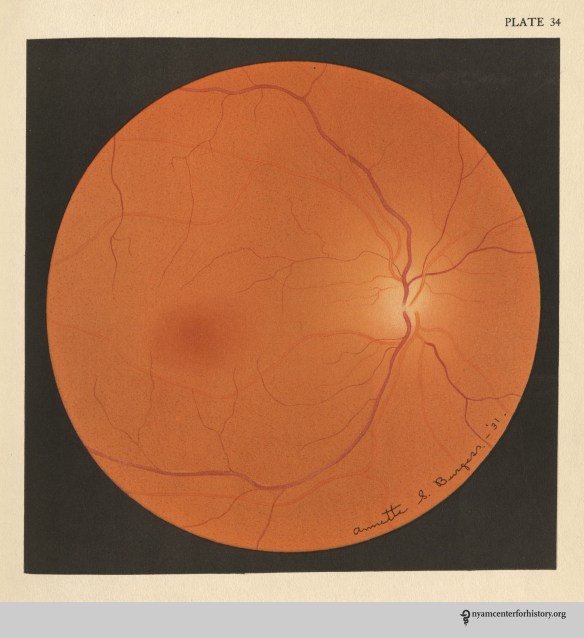

Burgess was more than qualified to take on this challenge. To make her paintings, she became a skilled user of the ophthalmoscope and the slit lamp. Writing about the process by which she created her illustrations, Dr Alan C. Woods explained that to show the ocular lesions related to a particular disease “she would make six drawings from different eyes depicting the various lesions and gradations thereof, rather than paint and sign her name to any drawing which was not a faithful portrayal of the lesions actually present in the eye under study.”[3] This meticulous work increased the value of the illustrations for users of the atlas, as their level of accuracy was extraordinary, rendering the experience of looking at the illustrations very close to that of looking through an ophthalmoscope itself. Some of Wilmer’s descriptions also include detailed half-tone illustrations of particular features he wanted to highlight; these, too, were drawn by Burgess.

“Choroiditis, Diffuse, with Ascending Perineuritis” (plate 34) halftones from Atlas Fundus Oculi (1934).

Burgess also collaborated with Woods, providing the illustrations for Endogenous Uveitis (1956) and Endogenous Inflammations of the Uveal Tract (1961), although in both of those volumes her paintings were reproduced using photographic processes rather than lithography, and reduced in size. While still extraordinarily beautiful, the texture found in the earlier lithographs disappears in the reproductions in these later publications.

Plates XXVII and XXVIII (left) and plates XXIX and XXX (right), from Endogenous Uveitis (1956).[4]

For decades after her death, the Department of Art as Applied to Medicine at Hopkins continued to celebrate Annette Burgess’s legacy with an award to honor excellence in ophthalmological illustration.

References:

[1] Davis RW. Annette Smith Burgess (1899-1962). Journal of the Association of Medical Illustrators. 1963; 14:25-28.

[2] Wilmer WH. Atlas Fundus Oculi. New York: MacMillan; 1934, p. 7.

[3] Woods AC. Obituary in “News and Comment.” Archives of Ophthalmology. 1962; 68(6): 880.

[4] Woods AC. Endogenous Uveitis. Baltimore: Wiliams & Wilkins, 1956.