By Anne Garner, Curator, Rare Books and Manuscripts

When Hogwarts librarian Irma Pince first appears in book one of the Harry Potter series, published twenty years ago this week, she is brandishing a feather duster and ordering young Harry out of the library where he’s pursing the noble (and ultimately world-saving) task of looking up the alchemist Nicholas Flamel.

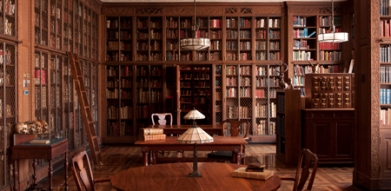

Drs. Barry and Bobbi Coller Rare Book Reading Room.

Pince doesn’t exactly scream poster-child for open access. And yet, a chance look at our card catalog recently revealed that the Academy Library might have something in common with Hogwarts, aside from its ambiance (The Library’s Drs. Barry and Bobbi Coller Rare Book Reading Room, nestled on a locked mezzanine level of the Academy that visitors sometimes call its “Hogwarts floor,” frequently invites comparisons.) That something is our collections.

To celebrate the twentieth anniversary of the publication of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, The New York Academy of Medicine Library has launched a special digital collection, “How to Pass Your O.W.L.s at Hogwarts: A Prep Course.” Featuring rare books dating back to the fifteenth century, the collection reveals the history behind many of the creatures, plants and other magical elements that appear in the Harry Potter series.

The digital collection is organized as a fictional study aid for Hogwarts students preparing for their important magical exams, the O.W.L.s. The collection is organized into seven Hogwarts courses, featuring historical content related to each area of magical study. For example, the Transfiguration section focuses on alchemy and the work of Nicholas Flamel—a historical figure who is fictionalized in Rowling’s books. Both Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone and seventeenth century scientific literature represent Nicholas Flamel as an important alchemist responsible for achieving the philosopher’s stone (the real Flamel was a wealthy manuscript seller, and likely never an alchemist himself).

Salmon, William. Medicina Practica, or the Practical Physician, 1707, featuring Nicholas Flamel’s Hieroglyphics.

The collection’s Care of Magical Creatures section features spectacular centuries-old drawings of dragons, unicorns and basilisks—plenty of prep material here to keep the attention of young wizards during this third year elective course.

The early naturalists Conrad Gessner and Ulisse Aldrovandi both devoted entire volumes of their encyclopedic works to serpents. Some illustrations depicted snakes as we might see them in the natural world. Others celebrated more fantastical serpentine creatures, including a seven headed-hydra and a basilisk. Said to be the ruler of the serpents, the basilisk (from the Greek, basiliskos, for little king) looks a little like a turtle with a crown on his head.

Aldrovandi, Ulisse. Serpentum, et draconum historiae libri duo…, 1640, pp. 270-271.

Aldrovandi, Ulisse. Serpentum, et draconum historiae libri duo…, 1640, p. 363.

Off campus proves to be where the wild (er) things are. In book one of the series, Voldemort gains strength by ingesting the blood of a unicorn. Rowling’s unicorns have healing properties and can act as antidotes to poison. The qualities Rowling assigns to these beautiful and rarest of beasts echo their characterization in early modern natural history texts. Several of these works —illustrated encyclopedias that depict and describe both real and fantastic animals in the sixteenth century—present the unicorn as powerful healers.

We’ve written already about the French apothecary Pierre Pomet’s illustrations of the five types of unicorns, and his assertion in his 1684 history of drugs that unicorn horns sold in most apothecary shops were actually the horns of narwhals.

Pomet, Pierre. Histoire generale de drogues, traitant des plantes, des animaux, & des mineraux…., 1694, p. 9.(Click Here for a coloring sheet of this image!)

Conrad Gessner’s 4500 page encyclopedia of animals, the Historia Animalium, also includes a depiction of a unicorn (below). Gessner writes that unicorn horn and wine together can counteract poisons, and assigns it other efficacious properties.

Gessner, Conrad. Thierbuch das is ein kurtze b[e]schreybung aller vierfüssigen thiern so…, 1563.

Schott, Gaspar. Physica curiosa; sive, Mirabilia naturae et artis libris XII…1667, p. 357.

While the History of Magic taught at Hogwarts is largely fictional, the Academy Library contains books in the real-life history of magic, including the 1658 manual Natural Magick by Giovanni Battista della Porta and a manual for witch-hunters by della Porta’s rival, Jean Bodin—two highlights of the digital collection. Another featured treasure is an actual bezoar (ours comes from the stomach of a cow, ca. 1862), and is used as a key potions ingredient by Hogwarts’ students.

As Hermione Granger says, “When in doubt, go to the library.” We hope you’ll heed her advice and check out our new digital collection, “How to Pass Your O.W.L.s at Hogwarts: A Prep Course.”