This guest post is by Matthew Davidson, a doctoral candidate at the University of Miami and the 2019 Paul Klemperer Fellow at the New York Academy of Medicine. His research examines public health in Haiti during the 1915-1934 U.S. occupation.

During the nineteen years of the early twentieth century that the United States occupied Haiti (1915-1934), U.S. officials liked to claim that they had brought modern medical thought to the Caribbean country. Their contention was bunk, but it apparently felt very real when the Haitian physician, Dr. François Dalencour, received a letter from a French colleague asking for copies of any Haitian medical publications. “I was ashamed,” Dalencour later wrote, “of being obliged to tell the truth, to say that there were none. [i] He would have been able to send along reports authored by the occupation medical service, but there was apparently nothing current otherwise. Haiti, Dalencour decided, needed a medical journal.

Soon after, he established one.

The first issue of Le Journal Médical Haïtien (NYAM).

The occupation, it turns out, was indeed an important period for Haitian medical thought. As was the case in other fields, it provoked a flurry of intellectual production. Consequently, whereas doctors such as Dalencour lamented the lack of Haitian medical publications at the start, by the end the local medical establishment could boast of several. U.S. officials claimed this was a sign of how far medicine in Haiti had “progressed” under their tutelage, but it was truly more the product of Haiti’s own medical tradition. [ii] Meant to advance medical practice and public health policy, the journals provided a forum for Haitian practitioners to debate and discuss all sorts of matters related to health and medicine in the country.

Dalencour’s periodical, Le Journal Médical Haïtien, was arguably the most important of the occupation-era publications. Not only was it the first, founded in May 1920, but it also did the most to open up space for the Haitian medical profession to articulate ideas and positions about their field. With U.S. personnel otherwise completely dominating all aspects of medicine and public health in Haiti, Le Journal Médical Haïtien was the only venue (outside of individual private practices) actually controlled by Haitians. It accordingly brought together “all members of the Haitian Medical Corps, without any distinction”: doctors, pharmacists, dentists and midwives. [iii] In doing so, the journal bridged longstanding divisions within the medical corps and laid the foundation for further independent initiative.

As Le Journal Médical Haïtien facilitated the reorganization of the Haitian medical profession, it also laid bare the lie that the occupation brought medical modernity to the country. After all, it was not because the U.S. introduced “scientific medicine” or any other set of ideas to Haiti that the journal appeared. Rather, it had its genesis in the pre-occupation period. As Dalencour wrote in the first issue, the project was first conceived in 1903. He was still a medical student at the time, so establishing a journal for medical reform was a “somewhat pretentious idea.” [iv] Nonetheless, it was then, well before the Americans landed, that the first steps were taken to establish a “general review of the medical movement in Haiti” (as Le Journal Médical Haïtien was later billed). The principles laid out by Dalencour and his collaborators in 1920 were even the same as those declared in 1903. All that had changed was the name. Dalencour had originally chosen the title Haïti Médicale, but – further reflecting the strength of Haiti’s pre-occupation medical and intellectual traditions – another journal had taken that name in 1910. [v]

The next to emerge was Les Annales de Médecine Haïtienne. Established in 1923 by two young doctors, Drs. N. St. Louis and F. Coicou, Les Annales was associated with a newly reorganized union, le Syndicat des Médecins. Much more oppositional in outlook, the journal was conceived as an “organ for the expansion of medicine in Haiti and for the defense of the interests of the medical corps.” [vi] Explicitly anti-occupation, it actively contested the U.S. health project in Haiti and worked to organize Haitian doctors against it under the auspices of le Syndicat des Médecins. It was not merely a political publication, though, for it also carried articles dedicated to public health education and research in the medical sciences. Over time, such articles became more and more prominent, and as the occupation ended Les Annales de Médecine Haïtienne essentially transitioned to purely scientific journal. U.S. medical sciences, however, continued to be received coolly.

May-June 1932 issue of Les Annales de Médecine Haïtienne (Schomburg Center, NYPL).

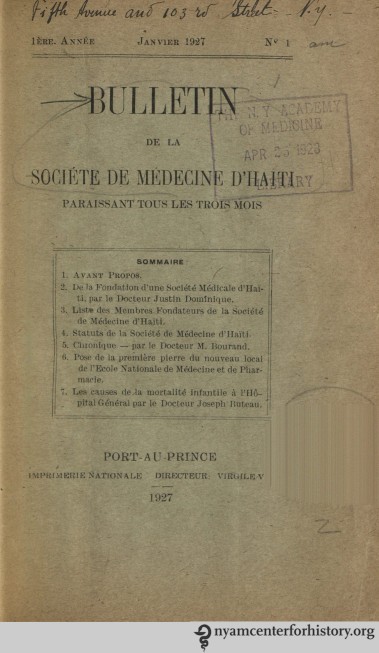

The last of the occupation-era publications was the only one that owed its existence to the occupation health project. The Bulletin de la Société de Médecine d’Haïti, founded with that society in 1927, was the sole journal fostered by U.S. officials, and it was the only one to have U.S. practitioners on its editorial board or to publish articles authored by occupation doctors. The society itself was organized and controlled by the occupation health service, the Service d’Hygiène. Accordingly, most independent doctors (i.e., those not directly employed by the Service d’Hygiène) tended to find the Société “too American” and remained outside of it. [vii] Nonetheless, the Bulletin was more than just an American journal based in Haiti.

The first issue of the Bulletin de la Société de Médecine d’Haïti (NYAM).

The Bulletin de la Société de Médecine d’Haïti was an important register for the medical sciences in Haiti. From 1927 until the end of the occupation, it published an impressive array of scholarship, much of it by Haitian practitioners. With an emphasis on medical specialization, it tended to be more concerned with the medical sciences than with public health policy or practice, and it accordingly developed a reputation for being the most scientific of the journals. As a project, however, the Bulletin mostly just brought to fruition ideas and proposals first put forth in the pages of Le Journal Médical Haïtien (or by the 1890 Société de Médecine de Port-au-Prince before that). In form as much as in content, then, the Bulletin was as Haitian as it was American. Consequently, when the American editors shuttered the journal in 1934 with the end of the occupation, the Haitian medical establishment remained committed to the project: it lived on as the Bulletin du Service d’Hygiene et d’Assistance Publique – Medicale et Sanitaire.

The first issue of the Bulletin du Service d’Hygiene et d’Assistance Publique – Medicale et Sanitaire (NYAM).

Each of these journals have largely been overlooked by historians, despite being incredibly rich sources. With their debates about public health policy, research on various health matters, clinical notes, correspondence between doctors and medical officials, translated articles from abroad, social commentary, and more, they offer significant insight into the state of medical care and the politics of health during the occupation. They would also be of interest to anyone thinking about Haitian social and intellectual history more generally. Few copies of each journal still exist, but they – with the exception of Les Annales – can be found at the New York Academy of Medicine library.

References

[i] Dalencour, François, « En Manière de Programme. » Le Journal Médical Haïtien (Première Année, No. 1, May, 1920; New York Academy of Medicine Library).

[ii] See, for instance, Parsons, Robert P., History of Haitian Medicine (New York: Paul B. Hoeber Inc., 1930).

[iii] Dalencour, François, « En Manière de Programme. » Le Journal Médical Haïtien (Première Année, No. 1, May, 1920; New York Academy of Medicine Library).

[iv] Dalencour, François, « En Manière de Programme. » Le Journal Médical Haïtien (Première Année, No. 1, May, 1920; New York Academy of Medicine Library).

[v] Haïti Médicale was published from 1910-1913, and then was briefly revived again in 1920.

[vi] Les Annales de Médecine Haitienne (9eme Année, No. 3 &4, Mars-Avril 1932; Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library).

[vii] Bordes, Ary, Haïti Médecine et Santé Publique sous l’Occupation Américaine, 1915-1934 (Haiti: Imprimerie Deschamps, 1992), 300.