This guest post is by Tina Peabody, 2019 Audrey and William H. Helfand Fellow at the New York Academy of Medicine, and a doctoral candidate in history at the University of Albany, SUNY focusing on the urban environment in the United States. She is currently completing her dissertation entitled “Wretched Refuse: Garbage and the Making of New York City”, a social and economic history of waste management in New York City between the 1880s and 1990s.

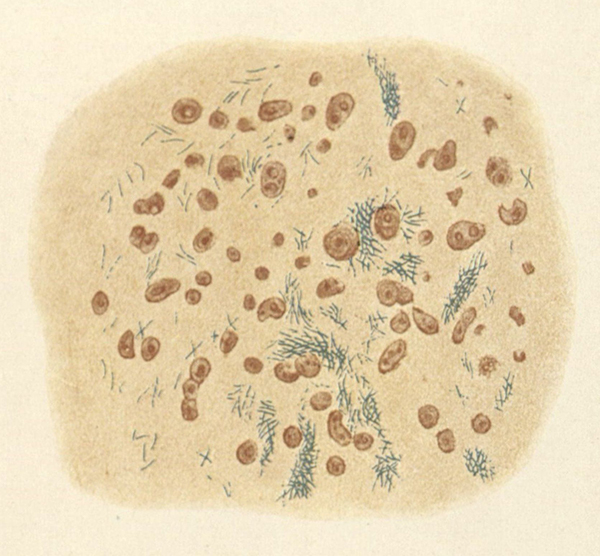

The Committee on Public Health at the New York Academy of Medicine is well known for their role in creating the Department of Sanitation in 1929, through the development of the Committee of Twenty on Street and Outdoor Cleanliness. However, the broader Committee’s activism on sanitation has a longer and more complex history. Soon after its formation in 1911, the Committee on Public Health decried the conditions of city streets. They held conferences on sanitation in 1914 and 1915 which included representatives of the Department of Street Cleaning and other municipal departments.[1] While Department of Street Cleaning Commissioner J. T. Fetherston claimed he could not update equipment nor flush streets with water, he nonetheless encouraged the Committee to educate the public about the connections between dirt and disease.[2] With that in mind, the Committee wrote a report in 1915 which connected the pathogens in street dirt to illness.[3]

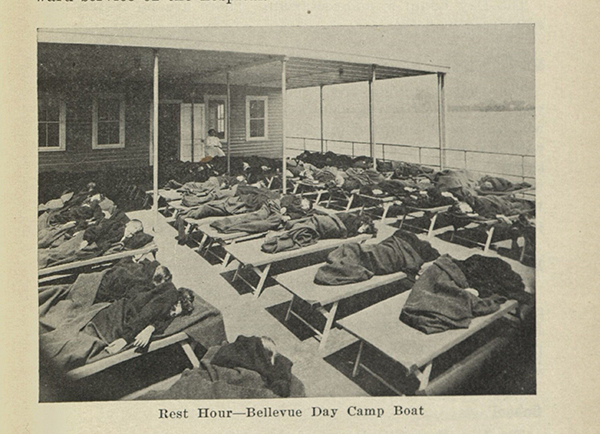

The Committee of Twenty was particularly concerned about open refuse trucks which could spew dust and debris. Images: Committee of Twenty, Committee on Public Health Archives, New York Academy of Medicine, ca. 1930.

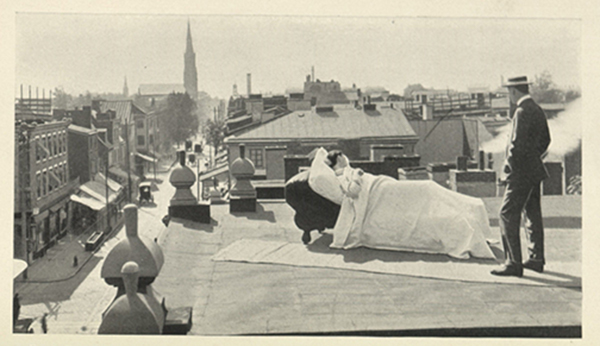

In 1928, a subcommittee called The Committee of Twenty was formed, in part because conditions did not improve substantially after the conferences and report.[4] Among their recommendations, the Committee of Twenty supported the creation of a unified sanitation agency with full control over street cleanliness.[5] They envisioned themselves as educators for the Department of Sanitation as well as the public, and they researched the latest collection methods and equipment from Europe to recommend improvements.[6] The newly-created Department of Sanitation, however, resisted investing in the recommended equipment, partially due to the expense.[7] Still, the Committee monitored street conditions, and kept photographic evidence of city and private sanitation trucks spewing dust and debris on the streets or other violations of sanitary ordinances.

Picture of overflowing refuse cans from the Committee of Twenty. Image: Committee of Twenty, Committee on Public Health Archives, New York Academy of Medicine, ca. 1930.

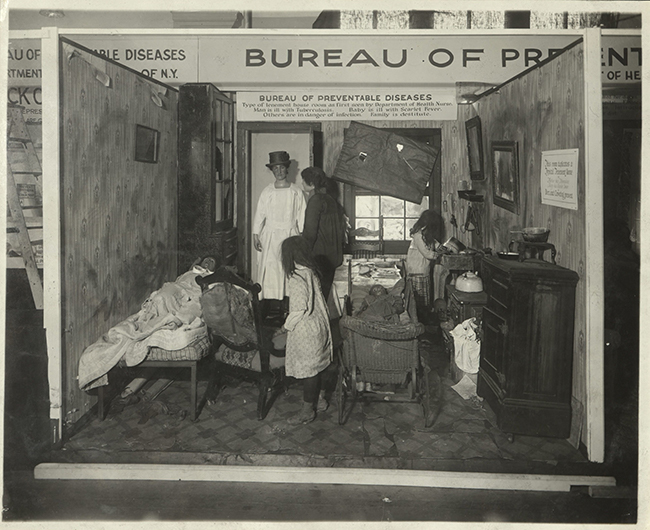

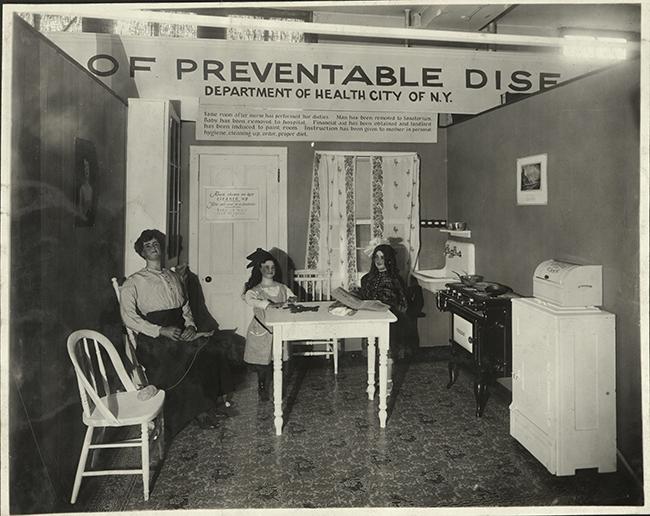

The Committee of Twenty also educated the public about outdoor cleanliness and especially the connections between dirt and disease. They issued pamphlets warning that “filth is the arch enemy of health,” and urged them to take personal responsibility for clean streets. “Do not put all the blame on the city administration,” one pamphlet read. “This is your city. A clean city means better health, better business; greater happiness for all; respect for law and order.”[8] Along with educational literature, they placed litter baskets around the city, and posted signs which reminded New Yorkers of sanitary practices like “curbing” dogs.[9] They also encouraged public participation in solving sanitary problem in novel ways, such as holding a contest for the best litter basket design in 1930.[10]

Educational Pamphlet from the Committee of Twenty. Image: Committee of Twenty, Committee on Public Health Archives, New York Academy of Medicine, ca. 1930.

The Committee was also influential in the citywide cleanup effort in preparation for the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Members of the Committee of Twenty and their allies argued that the Fair was the perfect opportunity for improving street cleanliness. Committee members Bernard Sachs and E. H. L. Corwin wrote that New York City was “the ‘Wonder City of the World,’ beyond a doubt; the ‘cleanest city,’ by no means. But we must make it that.”[11] In line with the idea, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia declared April 1939 “dress up paint up” month, and launched a broad beautification effort which included removal of litter, dog waste, and even “beggars, vagrants and peddlers.”[12] Bernard Sachs was the representative for the Committee of Twenty on the Mayor’s Committee on Property Improvement, which was developed for the cleanliness campaign.

Educational pamphlet from the Committee of Twenty. Image: Committee of Twenty, Committee on Public Health Archives, New York Academy of Medicine, ca. 1930.

Educational pamphlet from the Committee of Twenty. Image: Committee of Twenty, Committee on Public Health Archives, New York Academy of Medicine, ca. 1930.

In 1950, the Committee on Public Health supported an initiative to introduce alternate side street parking to allow street cleaning unobstructed from parked automobiles, but otherwise was much less active on sanitation issues after the 1939 World’s Fair.[13] At a meeting with Department of Sanitation Commissioner Andrew Mulrain in 1950, the Committee even debated whether unclean streets actually did cause disease.[14] One Dr. Lincoln wondered if clean streets were not simply a matter of “public pride.” [15] Still, the Committee’s early work on outdoor cleanliness would have a lasting legacy, particularly in terms of public education. The Outdoor Cleanliness Association, which was formed shortly after the Committee of Twenty [16], continued their educational work with regular cleanliness drives through the 1950s and 1960s in coordination with the Sanitation and Police departments.

References

[1] “Minutes of the Meeting of the Public Health, Hospital, and Budget Committee October 26, 1914,” The Public Health Committee of the New York Academy of Medicine Minutes 1914–1915 (New York, NY), 74; “Minutes of the Meeting of the Public Health, Hospital, and Budget Committee Conference on Street Cleaning May 7, 1915,” The Public Health Committee of the New York Academy of Medicine Minutes 1914–1915 (New York, NY), 153–55.

[2] “Minutes of the Meeting of the Public Health, Hospital, and Budget Committee,” November 16, 1914, The Public Health Committee of the New York Academy of Medicine Minutes 1914–1915 (New York, NY), 84–85; “Minutes of the Meeting of the Public Health, Hospital, and Budget Committee Conference on Street Cleaning May 7, 1915,” The Public Health Committee of the New York Academy of Medicine Minutes 1914–1915 (New York, NY), 153-54 .

[3] Committee on Public Health, “Thirty Years in Community Service 1911–1941: A Brief Outline of the Work of the Committee on Public Health Relations of the New York Academy of Medicine” (The New York Academy of Medicine, 1941), 79.

[4] Committee on Public Health, “Thirty Years in Community Service 1911–1941,” 80.

[5] “Minutes of the Meeting of the Executive Committee of the Committee on Public Health Relations,” May 14, 1928, The Public Health Committee of the New York Academy of Medicine Minutes 1927–1928 (New York, NY), 134; Committee on Public Health, “Thirty Years in Community Service 1911–1941: A Brief Outline of the Work of the Committee on Public Health Relations of the New York Academy of Medicine,” 10.

[6] Committee on Public Health, “Thirty Years in Community Service 1911–1941,” 80.

[7] Committee on Public Health, “Memorandum of a Conference between Dr. William Schroeder, Jr., Chairman, Sanitary Commission…..May 19, 1931,” 1–4, Committee on Public Health Archives, Box 4, Folder 50c.

[8] Committee of Twenty on Street and Outdoor Cleanliness, “Why Clean Streets? Because Filth Is the Arch Enemy of Health” (New York Academy of Medicine, n.d.), Special Collections, New York Academy of Medicine Library.

[9] Committee on Public Health, “Thirty Years in Community Service 1911–1941: A Brief Outline of the Work of the Committee on Public Health Relations of the New York Academy of Medicine,” 80.

[10] Committee of Twenty on Street and Outdoor Cleanliness, “Prize Contest for the Design of a Litter Basket For New York City” (New York Academy of Medicine, n.d.), Special Collections, New York Academy of Medicine Library.

[11] Bernard Sachs and E. H. L. Corwin, “Fair Offers Opportunity: City Is Urged to Institute a Program of Outdoor Cleanliness,” New York Times, July 4, 1938.

[12] Marshall Sprague, “Clean City for Fair: Public and Private Groups Hard at Work Dressing Up New York for April, 1939 Mayor Is Enthusiastic Keeping Waters Pure Refurbishing Statues Beautification Drives,” New York Times, September 18, 1938; Elizabeth La Hines, “Drive Is Begun For a Tidy City During the Fair: Outdoor Cleanliness Group to Ask Wide Aid in Fight on Sidewalk Rubbish One Nuisance Abated Aid Through New Equipment Model for Other Cities,” New York Times, April 9, 1939.

[13] Committee on Public Health, “Pioneering in Public Health for Fifty Years” (The New York Academy of Medicine, 1961), 62.

[14] “Minutes of the Meeting of the Subcommittee on Street Sanitation,” June 21, 1950, The Public Health Committee of the New York Academy of Medicine Minutes 1949–1950 (New York (N.Y.)), 473.

[15] Ibid.

[16] George A. Soper, “Attacking the Problem of Litter in New York,” New York Times, November 5, 1933.