Photograph of William Osler. Osler, W., & Pollard, A. W. (1923). Incunabula medica: A study of the earliest printed medical books 1467–1480. Oxford: Bibliographical Society. NYAM Collection.

December 29, 2019, marks the centenary of the death of Sir William Osler (1849–1919), arguably the most important and most loved physician of his era. Osler received his medical degree from MGill University in 1872, and joined the medical faculty there in 1874. A decade later he moved to Philadelphia to chair the department of Clinical Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, and in 1889 he was one of the founders of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, serving as its first Physician-in-Chief and as the first professor of medicine at the newly opened medical school. In 1905, he left the United States to become the Regis Professor of Medicine at Oxford, a position he held for the rest of his life. An accomplished teacher of clinical medicine, Osler established the medical residency program at Hopkins and made sure that students had ample opportunity to interact with patients at the bedside. His textbook, The Principles and Practice of Medicine, first published in 1892, appeared in multiple editions and was the standard textbook of internal medicine for decades. (National Library of Medicine, 2013).

Osler was also an extraordinary collector and lover of books, and in addition to amassing the collection that became the Osler Library of the History of Medicine at McGill University, he bestowed gifts on both his friends and on institutions. The Library of The New York Academy of Medicine has him to thank for two of its most treasured items.

Late in February of 1906, Osler sent a postcard to Walter Belknap James (1858–1927), along with a copy of William Harvey’s 1628 De motu cordis, the text in which Harvey describes the circulatory system and the motion of the heart and the blood. Harvey’s work, probably the most important text in the history of physiology, was notoriously difficult to find. In the Bibliotheca Osleriana, Osler recounts his hunt for a copy of the book:

Feb. 17, 1906; I had been looking for a copy for nearly ten years. Pickering and Chatto sent one to-day, which they had bought for £30 at the sale of Dr. Pettigrew’s library. Though a poor copy, measuring only 7 3/8 x 5 3/8 inches, I took it. Feb. 19, two days later, they sent me another (this one) from the library of Milne Edwards… I took it too, and passed on the other to Dr. Walter James who gave it to the Library of the Academy of Medicine, New York. (Osler, Francis, Hill, & Malloch, 1929, p. 4)

As can be seen in the image of the postcard below, Osler marketed this copy to James rather differently:

Postcard to Walter Belknap James from William Osler, February 1906. NYAM Collection.

Good copy or not, the gift of the Harvey definitely enhanced the Library’s holdings, and was joined later in the 20th century by a second copy of the 1628 edition when Robert Levy gave his library of books by and about William Harvey to the Academy Library.

Title page. Harvey, W. (1628). Exercitatio anatomica de motu cordis et sanguinis in animalibus Guilielmi Harvei. Francofurti: Sumptibus G. Fitzeri. NYAM Collection.

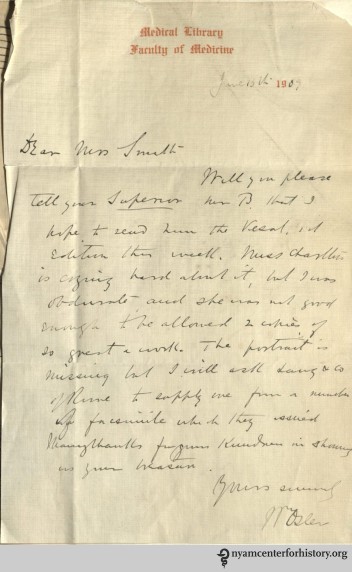

In 1909, Osler again made a gift to the Academy’s collections. On June 16th, Osler sent Laura Smith, who worked in the library, a note relaying the following information: “Will you please tell your Superior, Mr. B [John Browne, the Academy’s librarian] that I hope to send him the Vesalius first edition this week.”

Letter from William Osler to Laura Smith, June 16th, 1909. NYAM Collection.

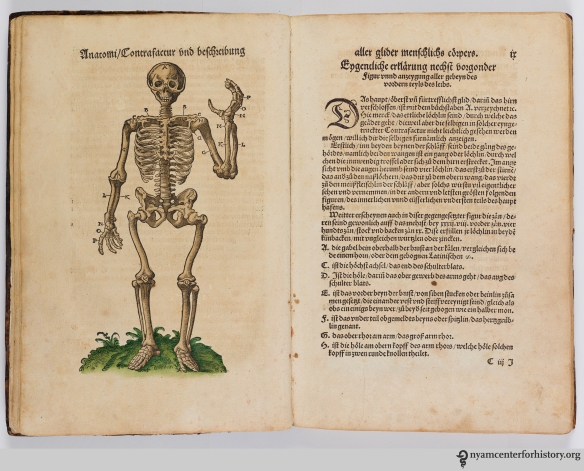

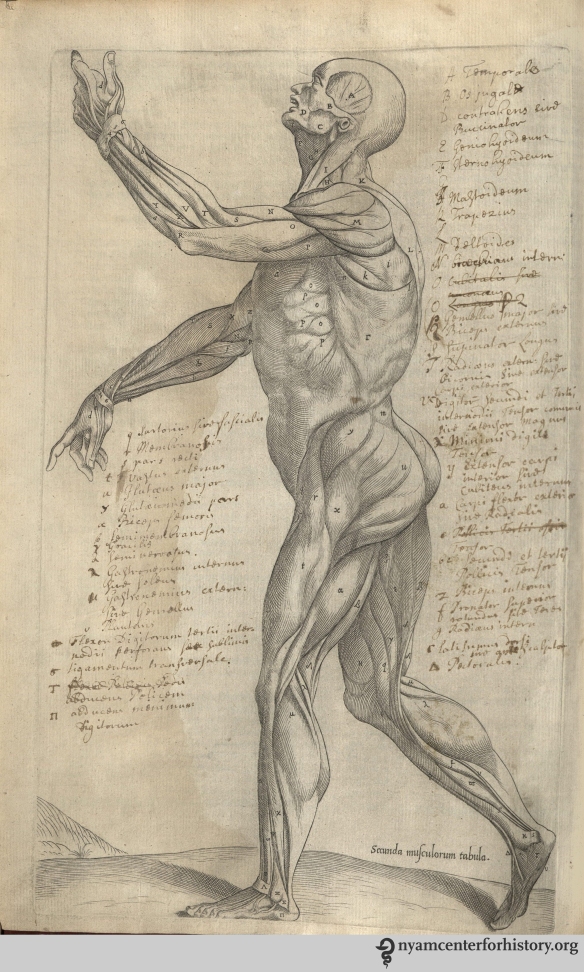

Osler had recently given a second copy of the 1543 edition of De humani corporis fabrica, Andreas Vesalius’ groundbreaking work on anatomy, to McGill, and decided that their other copy should make its way to the Academy, even going so far to say in his letter to Miss Smith that while Miss Charlton (of McGill) was “crying hard about it,” Osler was “obdurate and she was not good enough to be allowed 2 copies of so great a work” (personal communication, June 16th, 1909).

In the Bibliotheca Osleriana, Osler writes that he had in his possession at one time or another six copies of the Fabrica, also giving them as gifts to the Boston Medical Library Association; the Medical and Chirurgical Faculty, Baltimore; the Medical Department at the University of Missouri; and to his friend Llewelys Barker, who was professor of anatomy at the University of Chicago, as a wedding present. (Osler, Francis, Hill, & Malloch, 1929).

The Library’s copy still displays the inscription Osler wrote on the free endpaper of this copy when he gave it to McGill in 1903, “The original edition of the greatest medical work ever printed, the one from which modern medicine dates its beginning. W. O.”

Osler’s inscription on endpaper in De humani corporis fabrica (1543). NYAM Collection.

Our copy also retains the bookplates that track its movement from McGill to New York:

Bookplates in the 1543 edition of De humani corporis fabrica. NYAM Collection.

The Academy soon acquired two other copies of the 1543 Vesalius, one from the Edward Clark Streeter Collection and the other from Dr. Samuel Lambert, as well as two copies of the 1555 second edition. In fact, editions of Vesalius and related works soon became a major research strength of the collection, continue to be heavily used by readers, and are frequently shared with visiting groups and classes.

As 2019 draws to a close, the Library is grateful to its many friends and donors, who, following the spirit of Sir William Osler, continue to enrich our collections today. One hundred years later, the memory of Osler’s generosity reminds us that these books still matter. Generations of earlier readers held the Osler copies of the Harvey and Vesalius in their hands over the course of hundreds of years before they finally landed on our shelves. It is a privilege to be able to continue to share them.

References

National Library of Medicine. (2013). William Osler: Biographical overview. Retrieved from https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/spotlight/gf/feature/biographical-overview

Osler, W., Francis, W. W., Hill, R. H., & Malloch, A. (1929). Bibliotheca Osleriana: A catalogue of books illustrating the history of medicine and science. Oxford: At the Clarendon Press.

![Rösslin_Byrth_1545_Recto-VersoTorso Eucharius Rösslin (d. 1526). The byrth of mankynde, otherwyse named The womans booke. [London: Tho. Ray[nalde]], 1545. The byrth of mankind is an English translation of Eucharius Rösslin’s Rosegarten, an obstetrical text first published in German in 1513. Widely read and translated, the Rosegarten was written for midwives and contains the earliest obstetrical woodcuts. The first English edition, based on a Latin translation, appeared in 1540. The second English edition was revised by the physician Thomas Raynalde in 1545. Raynalde incorporated the work of other authors, including illustrations and descriptions from Vesalius’ Fabrica, such as these torsos.](https://nyamcenterforhistory.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/rocc88sslin_byrthe_1545_recto-versotorso.jpg?w=216&resize=216%2C198&h=198#038;h=198)