By Erin Albritton, Head of Conservation, and Christina Amato, Book Conservator, Gladys Brooks Book & Paper Conservation Laboratory

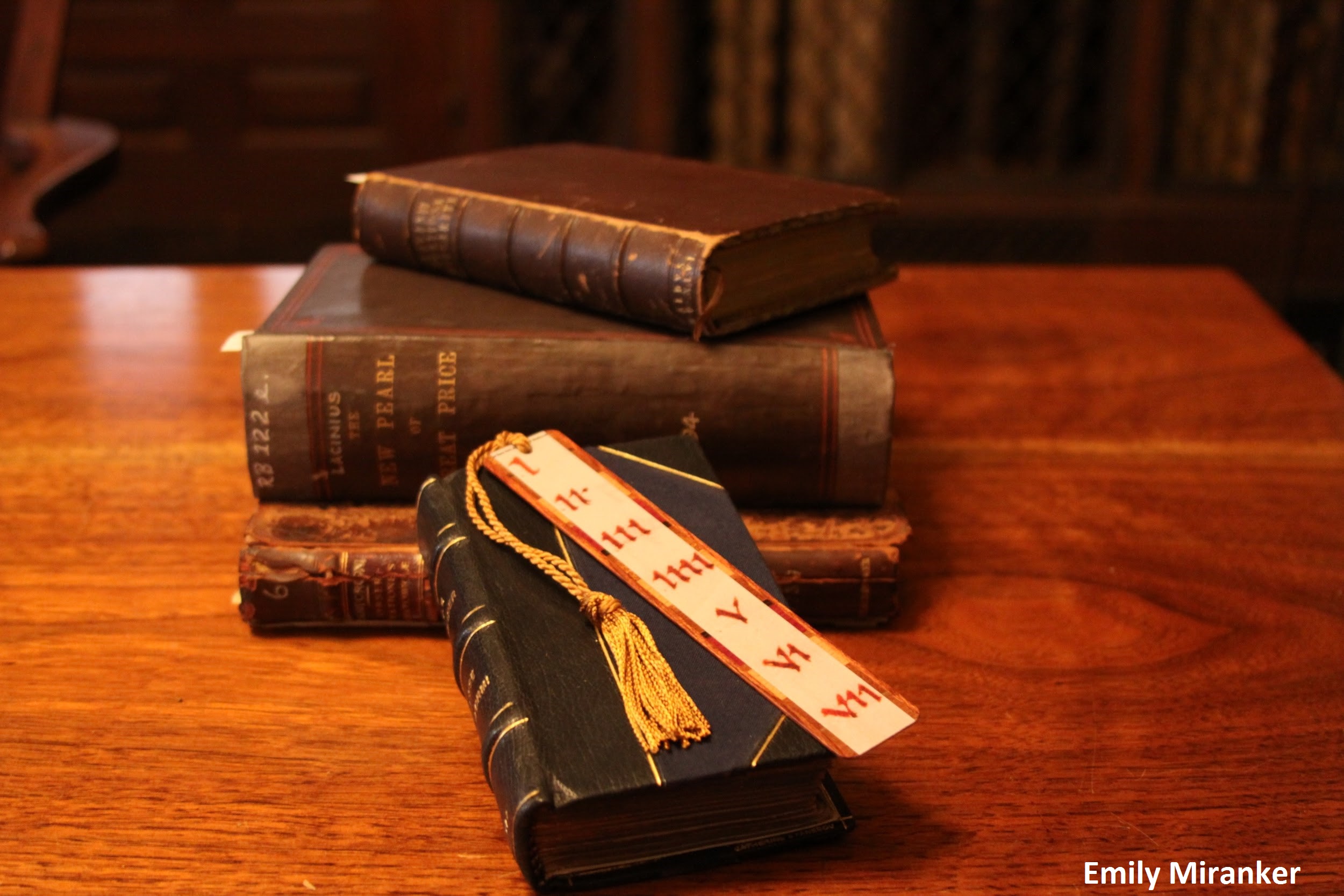

In the summer of 2013, conservators in the Gladys Brooks Book and Paper Conservation Laboratory began investigating conservation treatment options for a 17th-century Parisian imprint. As part of this process, we undertook an examination of a significant portion of The Academy’s early modern parchment volumes and became fascinated with a particular binding style—known as a semi-limp parchment binding—that has received very little attention in the published literature. For April’s item of the month, we offer a sneak peak at some of these bindings and the features that make them unique.1

A group of semi-limp parchment bindings in The Academy’s rare book collection

Parchment2 bindings can be grouped into three basic categories: limp, semi-limp, and stiff. As the name implies, limp bindings are supple structures characterized by the absence of boards beneath their simple covers. Stiff board bindings, on the other hand, live up to their name through the addition of two rigid pieces of board inserted at the front and back. Semi-limp bindings—the category on which we focus here—fall somewhere in between: supple, but due to the presence of flexible boards, not quite limp.3

The most common type of semi-limp binding represented in the The Academy’s collection has two flexible boards that “float,” unadhered, beneath its parchment cover (see picture below).

Floating boards within the detached parchment cover of a 17th-century Belgium binding. Tournai, 1668.

During our research, however, we were excited to discover a style of semi-limp parchment binding previously unknown to us—a structure distinguished by the fact that it has a single piece of thin moldable board (rather than two floating boards) inserted beneath its cover (see picture below). The board is wrapped around the whole textblock, the outer parchment cover is folded over it, and both are attached to the textblock at the head and tail via laced endband cores. For lack of any historical name, and to distinguish it from the floating boards binding mentioned above, we have called this structure a wrapped board binding.4

Wrapped board binding with inner paper board stiffener visible through damaged outer parchment cover. Lyon, 1641

As illustrated in the photographs below, the two styles outwardly appear very similar and can be almost impossible to tell apart without access to and close examination of the inner joints and spine.

Left: Floating boards binding, Paris, 1645. Right: Wrapped board binding, Paris, 1628.

To learn more about these structures, we undertook a two-part survey of The Academy’s rare book collection. Part one was a big-picture analysis, in which we examined approximately 20,000 volumes and collected basic information about every parchment binding we found; part two involved a detailed look at the semi-limp structures we identified during part one.

The results of our survey indicate that semi-limp bindings were much more popular in Europe during the early modern period than we suspected. Indeed, given the proportion of scholarly literature devoted to limp parchment bindings and their profile within the pantheon of historical binding structures, we were surprised to count nearly four times as many semi-limp bindings (of both the floating boards and wrapped board varieties) as limp bindings in our collection—with 194 and 48 respectively. Within our survey sample, the wrapped board structure was relatively uncommon—appearing on only 28 (or 14 percent) of all semi-limp bindings—and its use seems to have been limited to France in the late 16th and early 17th centuries.5

Title page from a Parisian wrapped board binding, 1639.

Almost all of the semi-limp parchment bindings we surveyed were simple structures—small in size and unornamented, featuring a number of structural shortcuts (including abbreviated sewing patterns on only two or three supports; simple endbands with minimal tie-downs; and plain endsheets of very basic construction) typical of retail (or, perhaps, less expensive bespoke) bindings of the time. While evidence indicates that these bindings were probably intended to be permanent,6 they were cheaper and easier to make (and, therefore, also likely less expensive to buy) than leather bindings. Hence, it appears that both the floating boards and wrapped board bindings were, in all probability, part of a larger strategy within the early modern book industry aimed at binding more books for a bigger audience quickly without going broke.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Our initial findings indicate that, like their limp parchment cousins, semi-limp bindings played a significant role in bookbinding history. This role has been both underappreciated and underexamined in the scholarly literature, however, and much research remains to be done. Consequently, we encourage readers to take a look beneath the covers of the parchment bindings that line the shelves of their collections and start documenting what they see.7

Notes

1. For definitions of some of the bookbinding terms used in this post, see Roberts, Matt and Don Etherington. Bookbinding and the Conservation of Books: A Dictionary of Descriptive Terminology. Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1982 (accessible online at http://cool.conservation-us.org/don//) or Carter, John and Nicholas Barker. ABC for Book Collectors. 8th ed., New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 2004 (accessible online at https://www.ilab.org/eng/documentation/29-abc_for_book_collectors.html).

2. Parchment is any animal skin that has been limed, de-haired, dried under tension, and then scraped and thinned. Although definitive species identification is not possible without DNA analysis, most parchment-bound books are made from sheep, goat or calf skin.

3. From the early 16th century on, binders began replacing traditional wooden boards with a variety of different types of cheaper paper ones. Most parchment bindings with boards were made using these.

4. Although much has been written about limp parchment bindings, we have found very little scholarly literature about their semi-limp cousins. The one notable exception is Nicholas Pickwoad’s 1994 study of the Ramey collection—a group of 359 volumes at the Morgan Library, printed mostly in France between 1485 and 1601—in which he identifies (for the first and, as far as we can tell, only time in an English-language resource) 46 examples of the wrapped board structure we describe here. See Pickwoad, Nicholas. “The Interpretation of Bookbinding Structure: An Examination of Sixteenth-Century Bindings in the Ramey Collection in the Pierpont Morgan Library.” The Library 6th s., XVII, no. 3 (September 1995): 209-249.

5. In The Academy’s collection, the wrapped board binding appears most frequently on French imprints published in Paris between 1620 and 1649. Although floating boards bindings were produced in a variety of different countries throughout the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, in The Academy’s collection they appear most often on Italian imprints published after 1640.

6. Unlike temporary bindings—which were made so that they could be removed and replaced with a more elaborate binding—these structures lack features (such as long sewing supports) that would have made rebinding easy, and are marked by others (such as trimmed and decorated textblock edges) that indicate permanence.

7. For those interested in learning more about this research project, a discussion of our survey results is anticipated to be published by The Legacy Press in 2016 as part of a collection of essays on the history of bookbinding titled Suave Mechanicals (Volume III).

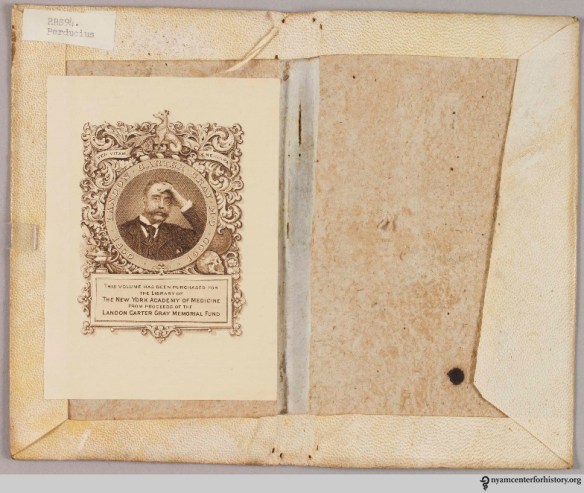

“On October 26th, the Academy Library convened ‘Archives, Advocacy and Change: Tales from Four New York City Collections.’ I moderated a lively conversation with all-star panelists Jenna Freedman (Barnard College), Steven Fullwood (In the Life Archive), Timothy Johnson (Tamiment Library, New York University) and Rich Wandel (The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center). The discussion hit on a lot of fascinating issues, including how archivists shape the historical record with the selection and acquisition choices they make, issues of privilege, and access for communities.”

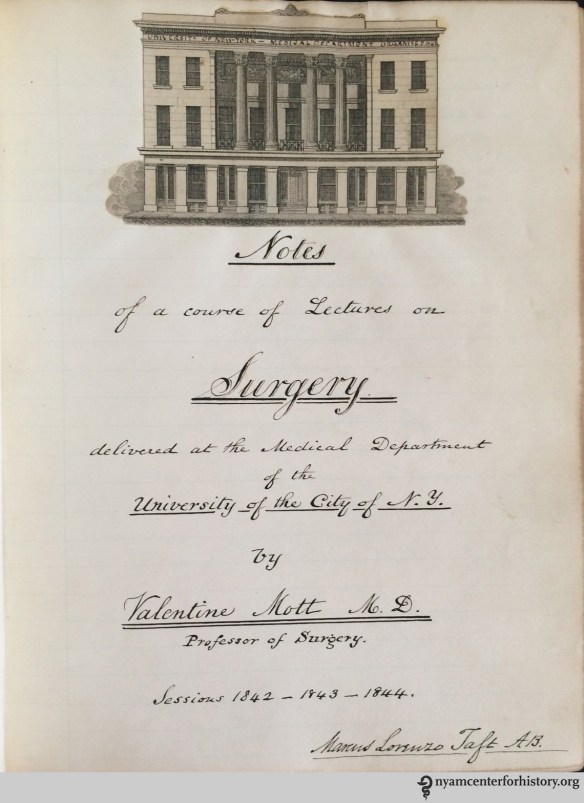

“On October 26th, the Academy Library convened ‘Archives, Advocacy and Change: Tales from Four New York City Collections.’ I moderated a lively conversation with all-star panelists Jenna Freedman (Barnard College), Steven Fullwood (In the Life Archive), Timothy Johnson (Tamiment Library, New York University) and Rich Wandel (The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center). The discussion hit on a lot of fascinating issues, including how archivists shape the historical record with the selection and acquisition choices they make, issues of privilege, and access for communities.”  “I was excited to learn in 2016 that the Library holds

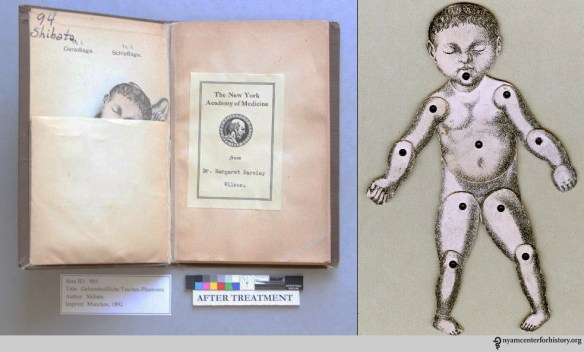

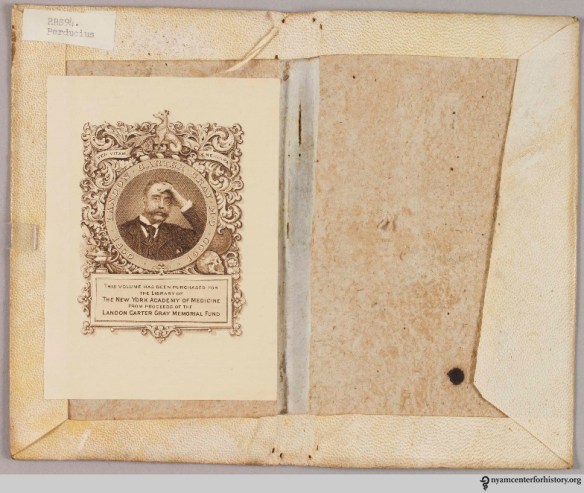

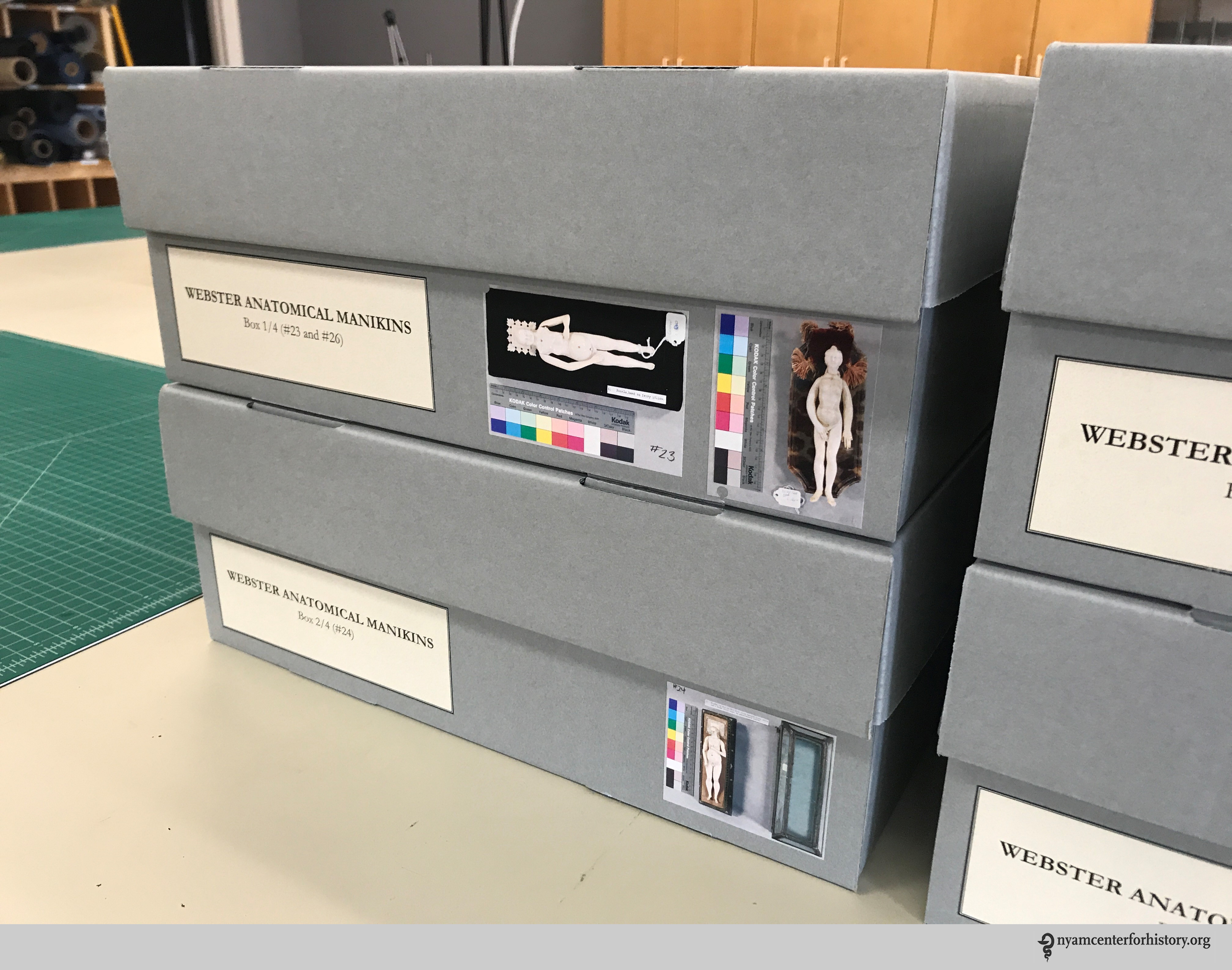

“I was excited to learn in 2016 that the Library holds  “Most of my works has a lot to do with satisfaction—satisfactions from cleaning dusted books, from placing crumbled health pamphlets into clean, acid-free envelopes, from making fitted enclosures for damaged books, from putting torn pieces together, and so much more. But all of these satisfactions is ultimately coming from that I’m contributing in preservation of the library materials to be more accessible and usable for the future! One of the most memorable item I worked through in

“Most of my works has a lot to do with satisfaction—satisfactions from cleaning dusted books, from placing crumbled health pamphlets into clean, acid-free envelopes, from making fitted enclosures for damaged books, from putting torn pieces together, and so much more. But all of these satisfactions is ultimately coming from that I’m contributing in preservation of the library materials to be more accessible and usable for the future! One of the most memorable item I worked through in  “A recent highlight for me would be our first

“A recent highlight for me would be our first

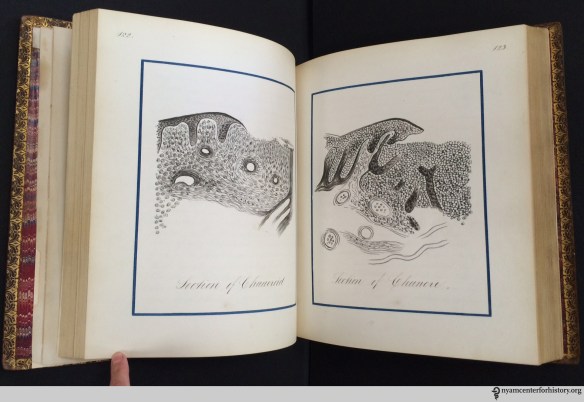

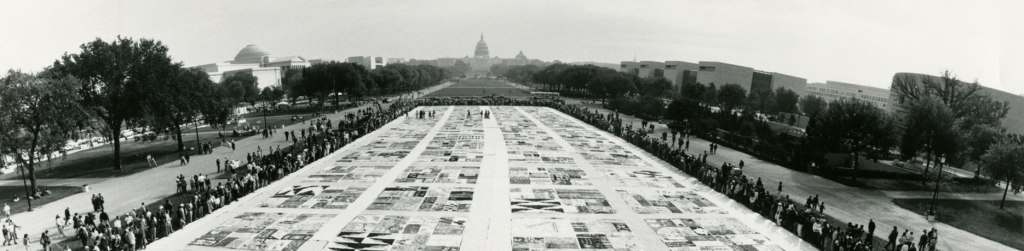

“Dr. Paul Schneiderman brought his Columbia dermatology residents to visit the rare book room on August 26th so that we could explore the history of dermatology. Looking at highlights from the dermatology collection from the 16th through the 20th centuries gave the residents a chance to think about the many ways in which their specialty has changed over time, especially since dermatology relies so heavily on visual representation. We looked at hand colored engravings, chromolithographs, photographs and stereoscopic images and the residents and their mentor engaged in lively debates about whether the descriptions and images matched with current information about some of the diseases that were shown. Not only did the residents have the opportunity to see these wonderful materials, but I had the pleasure of learning more about how to interpret the images from them.” –Arlene Shaner, Historical Collections Librarian

“Dr. Paul Schneiderman brought his Columbia dermatology residents to visit the rare book room on August 26th so that we could explore the history of dermatology. Looking at highlights from the dermatology collection from the 16th through the 20th centuries gave the residents a chance to think about the many ways in which their specialty has changed over time, especially since dermatology relies so heavily on visual representation. We looked at hand colored engravings, chromolithographs, photographs and stereoscopic images and the residents and their mentor engaged in lively debates about whether the descriptions and images matched with current information about some of the diseases that were shown. Not only did the residents have the opportunity to see these wonderful materials, but I had the pleasure of learning more about how to interpret the images from them.” –Arlene Shaner, Historical Collections Librarian