Annie Robinson, today’s guest blogger, holds a Master of Science in Narrative Medicine from Columbia University. As an eating disorder recovery coach, wellness educator, and workshop and retreat leader, Annie uses story to facilitate healing, self-reflection, and narrative competence. She will lead a Health and Social Justice Reading Group at the Academy six Wednesday afternoons from June 22 to July 27. Find out more and register online.

In middle school I developed a severe eating disorder that persisted into my mid-twenties. I have told this story in so many ways over the years. Initially, I subscribed to the common narrative of disorder-as-enemy: “I am battling an eating disorder.” But ultimately, this story did not serve my healing. It made me feel like I was at the mercy of my symptoms. Perceiving my eating disorder as a demon that I needed to fight against positions me as an enemy of myself, insofar as the eating disorder is inherently a part of me.

So I tried out a new story. What if my eating disorder is a wounded part trying to protect me from pain? It offers temporarily helpful—though ultimately ineffective—strategies to meet my needs for comfort and safety. It is young and naive, frantic and scared. It needs to be loved and listened to, not condemned and silenced. I took on the role of mother caring for a feisty, frightened child who needed firm but kind parenting. My mothering self and my eating disorder self engaged in frequent dialogues, both out loud and in writing, to rework the stories I’d been living for so long.

To truly enter recovery, I had to not only rewrite the story of my eating disorder, but to share it with others. As author instead of victim, I am freed from the secretiveness and shame that eating disorders thrive on. And by sharing my story, I make myself vulnerable, which allows me to connect authentically with others.

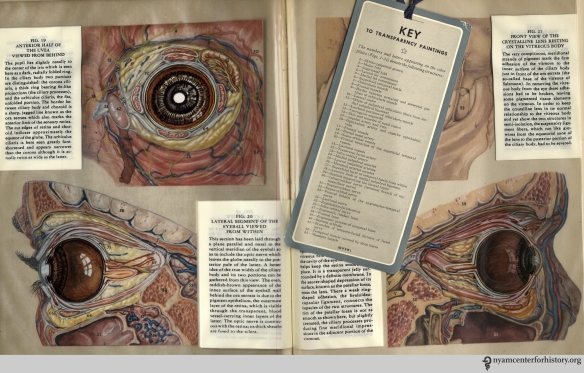

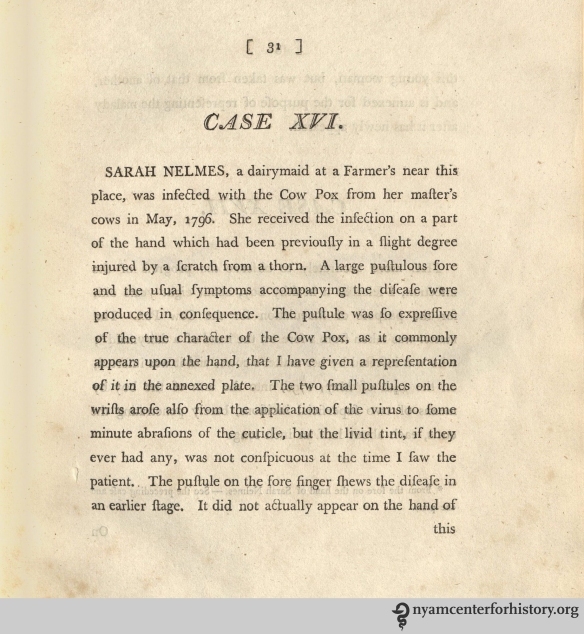

Using poetry for self-reflection and healing

Renowned researcher Brené Brown studies the correlation between exposing shame, embracing vulnerability, and wellbeing. Her research also examines how the stories we tell about ourselves possess tremendous power—either to trap us, or to instigate radical change. She postulates: “When we deny the story, it defines us. When we own the story, we can write a brave new ending.”

By changing my story, I changed my behaviors, and by changing my behaviors, I changed my life. While stories can disempower, they can also generate agency. They can ascribe blame, or bestow forgiveness. At their best, I believe stories are some of our greatest tools for healing both individual pain and social injustices.

I realized the potency of language not only in recovery, but also in my role as a doula—someone trained to support individuals as they navigate pregnancy, abortion, birth, and fetal loss. In this role, I have witnessed how issues of social justice are deeply entwined with bodily experiences.

Maria, a quiet 16-year-old Hispanic girl living a foster care home for pregnant teens, was 36 weeks along when I met her. For the majority of her labor at a large hospital in the city, no one looked her in the eye. Family-less, jobless, degree-less, and soon to be responsible for a newborn, she seemed too much for her providers to bear. Her labor was blessedly short, her birth smooth, and her beautiful baby boy healthy. But no one showed up to celebrate with her. Though she spoke no words of disappointment, tears welled in her downcast eyes as she smiled down at her tiny child.

Pooja, a vibrant 30-year-old Bengali woman in her second trimester of pregnancy, came into my care at a public hospital. She had just learned that if she carried her pregnancy to term, her baby would be born with severe disabilities. She had no choice but to terminate the pregnancy, because she and her husband could not financially accommodate a child with expensive chronic medical needs. During the termination procedure, she wailed and dug her nails into my hand as I held fast, whispering soothing words in her ear. As her cries escalated, the doctors spoke louder to her in English (a language she barely understood) about what steps they were taking, as if they could extinguish her deep suffering with their voices and expertise.

The stories of Maria and Pooja, along with those of dozens of other women I have served, reflect how social injustice is so often based in the body. Their distinct cultural conditions, social vulnerabilities, and economic disparities all influenced the care they received.

In the world of medicine, the term “social justice” refers to the differences in how people experience health conditions and interface with the healthcare system. It is imperative to consider the roles these factors potentially play in the story of someone’s health experience, leading to inequities in resources, unique linguistic and cultural reference points, and distinct vulnerabilities and disadvantages.

While serving as a doula, I also was a graduate student at Columbia University studying an innovative discipline called narrative medicine. This approach endeavors to train clinicians to deeply hear and respond to their patients’ stories, not just their symptoms. Narrative medicine provides a way for patients and providers to co-create humanized stories of illness and embodied experiences, and offers strategies for studying the meaning of these experiences through telling, reading, and writing about them. I came to appreciate body-based stories as deeply vulnerable ones, as they concern both our physical selves as well as the parts of our identity that transcend biology.

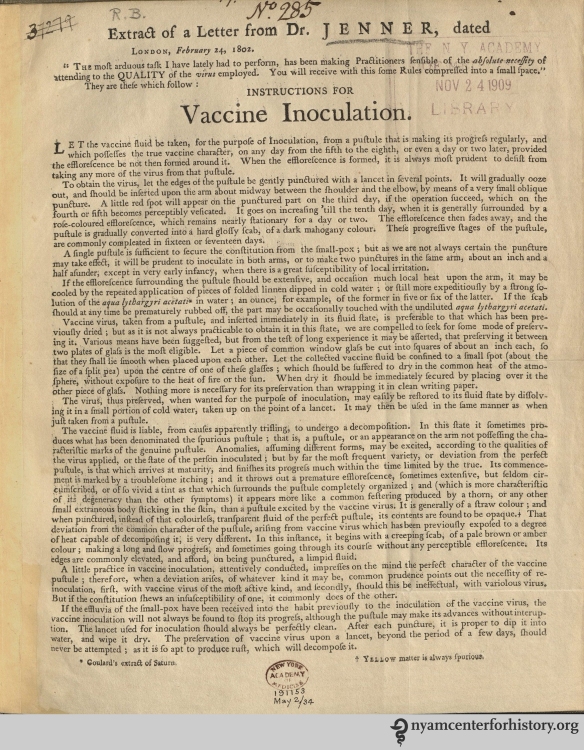

I will be facilitating a six-week course at the New York Academy of Medicine from June 22-July 27, 2016 on how language can serve as a mechanism for social justice in health (register online). We will use narrative practices such as reading fiction and nonfiction texts, having group discussions, and writing self-reflectively for an in-depth exploration of how language influences our experiences of our bodies and can serve as a mechanism for enacting social justice in healthcare.

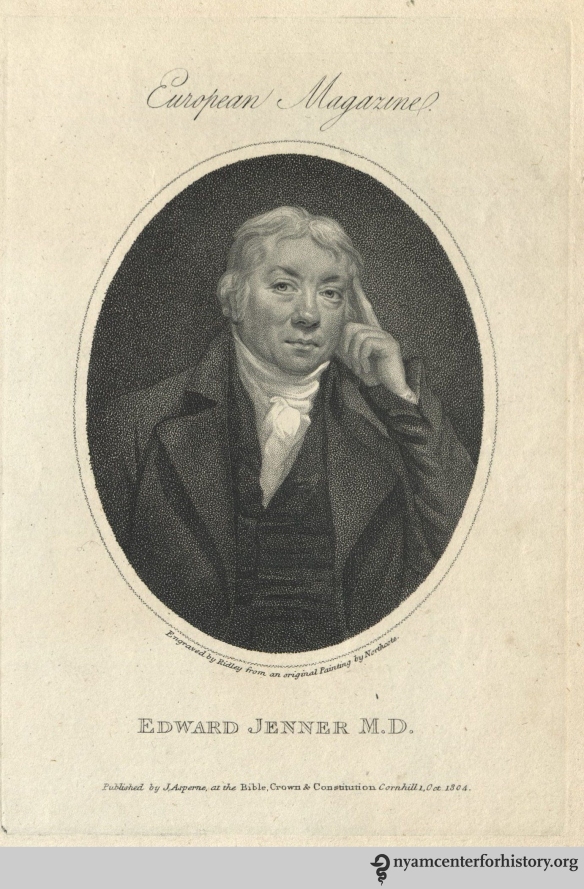

Workshop on stories and self-care led by Annie Robinson, November 2015.

We will use narrative depictions to unpack how health, illness, and disability are issues of social justice. How do social justice and health relate to gender, sexuality, race, trauma, caregiving, privilege, disability, age, class, and geography? How can creative expressions of embodied experiences facilitate self-realization and healing? Whose voices are most often heard, and whose are not? Where do private matters of health, illness, and disability fit in the public arena? What are the effects of how they are politicized, for better and for worse? And how can social, cultural, and political change that benefits embodied experiences be instigated by individuals?

Sources will include (among others): poems by physician-poet Rafael Campo, stories by Sherman Alexie, essays by Eve Ensler, excerpts from Illness as Metaphor by Susan Sontag, first-person perspectives about gendered embodiment from Minding the Body, and pieces from Leslie Jamison’s The Empathy Exams.

Please join us to explore what social justice, story, and embodiment mean to you!

Questions? Please email culturalevents@nyam.org.