By Mario Rubano, MPH, Center for Healthy Aging, NYAM

Today’s guest blogger is Mario Rubano, Policy Associate at NYAM’s Center for Healthy Aging. Mr. Rubano plays a central role in the Academy’s next Then & Now event, “The Opportunities and Challenges of Healthy Aging in New York City.” He conducted the interviews documenting the experiences of older New Yorkers and will moderate the discussion of those experiences with historians Kavita Sivaramakrishnan, PhD, and David G. Troyansky, PhD. The event takes place online on Tuesday, November 15, 5:00 to 6:00 pm; you can register here.

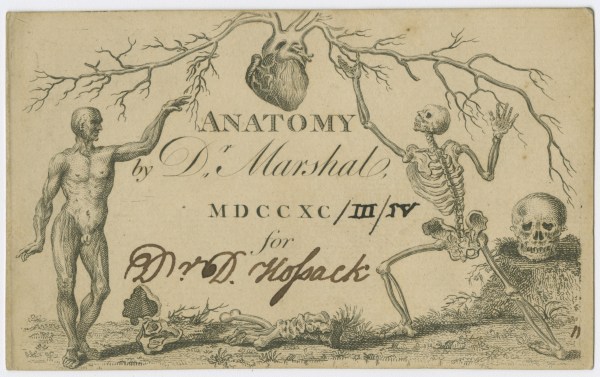

The NYAM Library’s “Then & Now” series has explored a wide variety of medical and public health issues, bringing experts and researchers into dialogue with the broader NYAM community. As the Academy’s 175th anniversary celebrations wind down, we’re delighted to feature a different set of experts—older New Yorkers.

NYAM has been at the forefront of NYC older adult health and policy since 2006, when it first joined the Global Age-friendly Cities project, an international effort spearheaded by the World Health Organization (WHO). The following year saw the development of Age-friendly NYC, an award-winning partnership that reimagined how the City could meet the needs of its older residents. This shift was rooted in the 8 Domains of Livability, a collection of interconnected categories that captured the most vital aspects of healthy living for older adults in urban centers. Today, the Center for Healthy Aging (CHA) embodies this legacy in its ongoing mission to improve the health and well-being of current and future aging populations.

At present, New York City is home to roughly 1.2 million individuals aged 65+, and we were lucky enough to settle down with five of the busiest of them for personal interviews via Zoom. The participants, drawn from a network of grassroots age-friendly community groups, shared their insights, memories, experiences, and opinions (with classic New York panache) in a discussion structured around the 8 Domains of Livability. Each of the participants has maintained an active relationship with local community-based organizations, community boards, volunteer groups, or, in one case, as a part-time Reservist working with NYAM. What was immediately clear across each of the interviews was the devotion that each participant has to this city. Whether born-and-bred or a transplant, these New Yorkers were as energized by the city as one could possibly be, and it’s this vigor that brought their reflections to life.

If a single takeaway were to be drawn from these five interviews, it would be that “progress” is a constant process rather than a state-of-being or condition that is achieved. The domain of transportation illustrates this idea. The participants all remarked on the tremendous improvements in comfort and capacity that the public transportation system has undergone over their lifetimes. The advent of air conditioning to ease the misery of a summertime, rush-hour commute, the growing fleet of accessible kneeling buses that simplify the boarding process for individuals with mobility challenges, and the creation of station transfers were all viewed as highlights over the years. Yet, we also heard about significant lapses in the management of bus lines that blatantly ignore the needs of older New Yorkers and, in many instances, place undue burdens on communities of color.

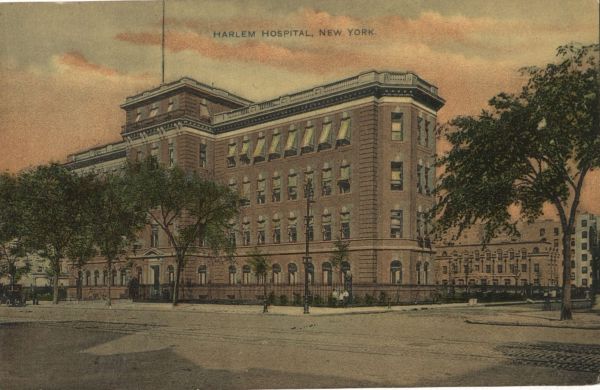

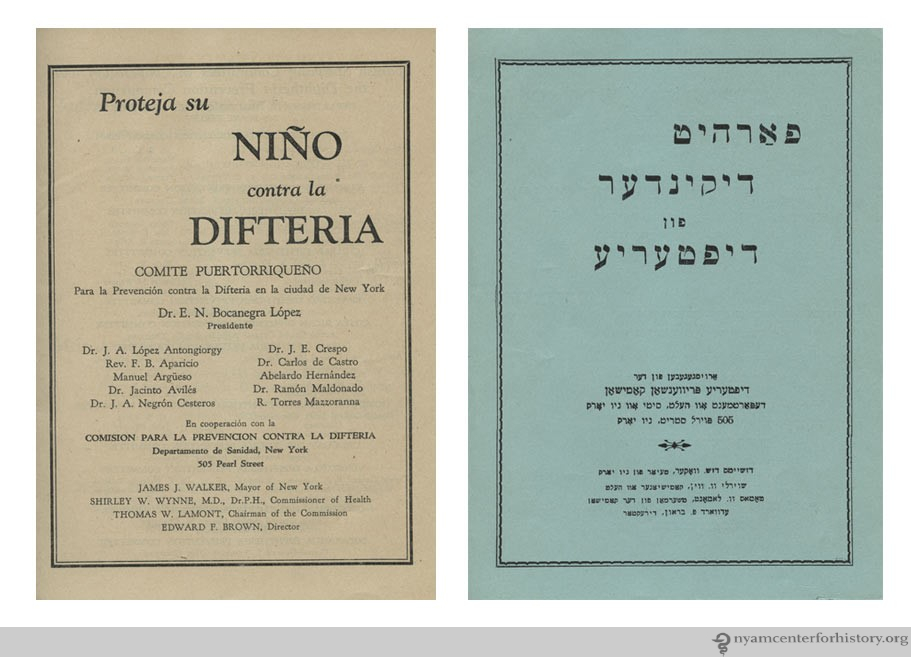

Healthcare access also changed in remarkable ways, both positive and negative, over the course of their lifetimes. House calls from family doctors who knew and treated entire communities gave way to newer models of care that, while noted for their efficiency and quality, were seen as impersonal and disconnected. We heard sobering stories of healthcare in the years before desegregation and the ongoing effects of Robert Moses’ infrastructure projects, like the Cross Bronx Expressway. These stories demonstrate the necessity of continued civic and community engagement, even after broad, landmark victories. Legislative progress—such as that initiated by the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990—must be continuously refined to ensure that the promises of better lives remain intact in an increasingly complex world.

This project has been a thrilling process in itself, and we look forward to sharing these New Yorkers’ stories, and hearing the commentary by our guest historians, Drs. Kavita Sivaramakrishnan and David Troyansky, at the upcoming November 15th Then & Now event.