By Miranda Schwartz, Cataloger

In May 2021, the Library rolled out an update to the Robert Matz Hospital Postcards Collection, one of the digital collections on our Digital Collections & Exhibits website. The upcoming Open House New York Weekend, October 16–17, seems like an apt time to share the updated collection with readers, as the digitized postcards provide a wonderful visual history of New York City hospitals and their architecture.

The Collection

Since 2015 Dr. Robert Matz has been graciously donating postcards of hospitals from his personal collection to the Library; he’s given about 3,000 postcards to date. The bulk of the collection shows hospitals in New York City, with smaller sub-collections of hospitals across the state and country. The collection provides a rich visual history of hospital buildings across decades, both exterior views as well as glimpses of patient wards and chapels, doctors and nurses, and even a children’s schoolroom. The collection also provides a look at postcard printing trends. Many of these buildings no longer exist, but seeing these postcards gives us invaluable visual information about them. In addition, the personal messages on the postcards provide readers with fascinating slices of everyday life.

2019 Pilot Project

In 2019 we began a pilot digitization project, scanning 119 postcards of New York City hospitals and uploading them to our website, arranged by borough. A blog post on February 21, 2020, by Robin Naughton, former head of digital, explained the pilot project and digitization process and launched the online collection. We were excited to give the public online access to these fascinating materials.

Time for an Update

In mid-2020, the Library team decided that a full update of the postcard project was needed to create more accurate metadata (data about data). We had taken the original information for the digitized postcards from an Excel spreadsheet created by volunteers; however, the postcard metadata needed standardization of terms and vocabulary and a consistent overall structure. Therefore, we undertook a general review and update.

Metadata Creation

As the cataloger, I created a set of metadata standards that aligned with best practices in the field. Each postcard would have the Library of Congress subject headings Hospitals and Hospital buildings as well as a standardized location heading, for example, Hospitals — New York (State) — Kings County. In a new spreadsheet I added standardized subject headings depending on what was visible in the postcard or read in the message. If there were trees in the postcard, I added Trees. All these subject headings are searchable so that a viewer can click on the word Trees in one postcard’s subject headings and generate a list of all postcards with Trees as a subject heading or even as a word in the description.

I rewrote the description of each postcard, transcribed the postcard messages, deleted unhelpful keywords, checked the dates of each postcard’s manufacture, checked the official hospital names, and checked the names of the printers and publishers. I was assisted by our summer intern, college student Liani Astacio, who transcribed postcard messages and addresses and checked hospital names, locations, and Library of Congress subjects. She also rewrote some of the postcard descriptions.

Research Sources

Metropostcard.com was an invaluable site for dating the postcards by their design features. The introduction of the divided-back postcard in the U.S. in 1907 was a major event in postcard history, and this fact alone helped me assign a date range to many of the postcards. For further help in dating, I looked up stamp prices using the USPS website and a Wikipedia page about postage rates. The home pages of many hospitals were also helpful in giving me a building chronology, as were various New York City architecture blogs.

Technical Process

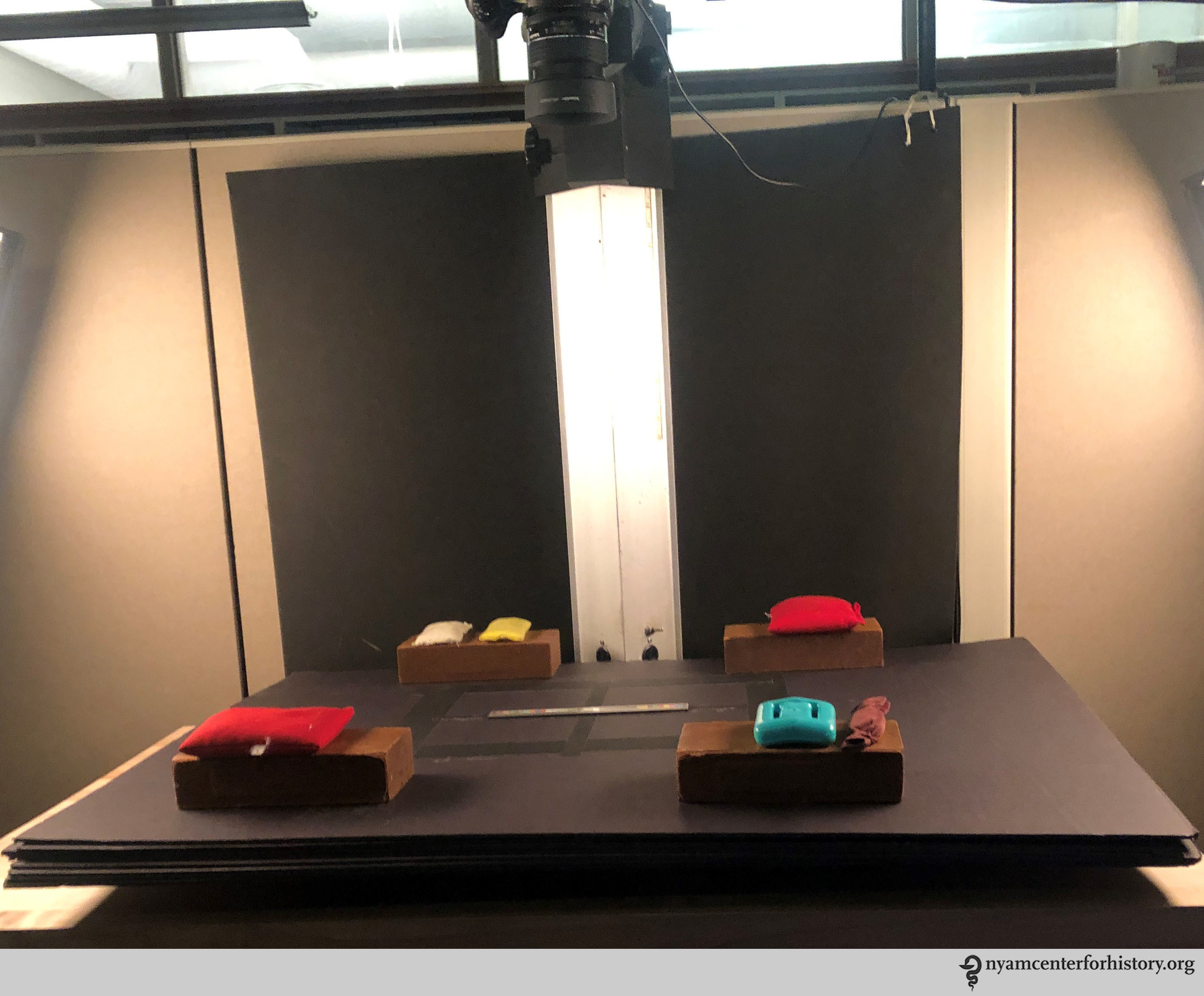

Updating each postcard individually would have been time-consuming so we created an automated process to batch update the postcards’ metadata. Andrea Byrne, the Library’s former digital technical specialist, saved the Excel metadata spreadsheet as a CSV file and then created individual MODS (Metadata Object Description Schema) XML files (3 for each postcard) that could be uploaded into Islandora, our digital asset management system. Her tools were the XML editing program Oxygen, and a script that she worked out with our Islandora vendor, discoverygarden inc. After the new MODS files replaced the existing MODS files online, I read each field of each postcard against the data in the Excel spreadsheet to check for accuracy, and Andrea made any necessary corrections. The update was complete!

The Updated Collection

The updated Robert Matz Hospital Postcards Collection went live in early May. We’re proud of our work, feeling that we’ve captured the unique elements of these images of hospital buildings and city street life. The engaging, information-rich postcards on our digital website are just a small part of the collection. Our hope is to digitize and create metadata for all the postcards in the Matz collection. Then viewers will be able to see thousands more postcards and delve further into hospital and postcard history.

Highlights from the Collection

A view of Montefiore Hospital and Medical Center in the Bronx highlights its entrance gate and driveway, with a group of people in the main doorway.

.

.

.

The ivy-covered walls of St. Catherine’s Hospital in Brooklyn are a dramatic backdrop to this glimpse of Brooklyn street life.

.

.

.

.

.

This Gothic Revival building at 106th Street and Central Park West housed New York City’s first cancer hospital and went through a number of iterations before falling into disrepair in the 1970s. The building was converted to luxury condominiums in the early 2000s.

.

.

This postcard for River Crest Sanitarium functions as an advertisement of available services, assuring its patients of a “home-like” atmosphere on its campus on Astoria.

.

.

Smith’s Infirmary Hospital was Staten Island’s first private non-profit hospital. The castle-like building was demolished in 2012, after years of neglect. Interestingly, the postcard is addressed to Miss Christine Geisel of Springfield, Massachusetts, the paternal aunt of famed children’s book author Dr. Seuss.

.

Sometimes a hospital doesn’t need to be a building! Here is the Floating Hospital, likely in the East River, with passengers aboard. The Floating Hospital wasn’t a true hospital, but rather a recreational service for children and their families; it provided onboard medical exams for children and child-care instruction for their mothers as they enjoyed summer boat outings. The organization later opened a hospital building, the Seaside Hospital on Staten Island.