By Paul Theerman, Ph.D., Director of the Library

A hundred years ago this week, medical doctor Lt. Charles Terry Butler (1889–1980) entered Germany with the Army of Occupation. Yes, the Armistice had been signed a full three weeks prior, but “Charlie’s war” was not yet over. He would remain in uniform for over four more months. Through his detailed memoir, A Civilian in Uniform [1], we have insight into his war service and the work of Evacuation Hospital #3, which followed the American war effort across France and into Germany in 1918 and 1919.

Image: A Civilian in Uniform, b/t. pp. 124-125.

As detailed in a previous blog entry, in 1916, Butler, newly graduated from medical school, spent six months as a volunteer surgeon in a British-French military hospital outside Paris, the “war before the war” for Americans. His experience at Ris-Orangis turned out to be crucial for his later war service. Three months after he returned home, the United States entered the war on the side of the Allies. Butler’s adventures over the next two years capture much of the American medical experience of the Great War.

Butler’s first “battle” was to avoid getting drafted into the infantry so that he could serve in the medical corps. A draft started right upon declaration of war on April 6th, and as a young man of 27, Butler was likely to be called up. He instead volunteered for the Army Medical Reserve Corps, where, with a medical degree, he received a commission as a first lieutenant in August. He was directed to go to Camp Greenleaf in Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia, by September 15th for additional training. [2] Afterwards, Butler shipped from Hoboken on January 12, 1918, bound for Saint-Nazaire, France, at the mouth of the Loire River, arriving on the 27th. Within a few weeks, Butler’s medical contingent was sent up the Loire and was divided, half to a hospital in Tours and half to one in Blois, both well behind the lines. He would serve separately in these locations over the next five months.

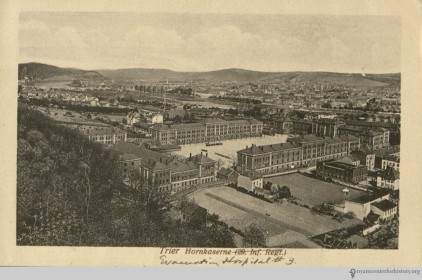

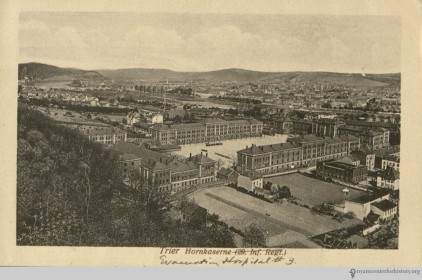

Postcard showing Evacuation Hospital #3. Image: Charles Terry Butler papers, New York Academy of Medicine.

Index to MOTC training lectures and notes. Image: Charles Terry Butler papers, New York Academy of Medicine.

In early July, as part of “Evacuation Hospital #3,” he was moved to Rimaucourt, in the département of Haute Marne, close to the front. On July 29th, the operation moved to La Ferté-Milon “70 K. from Paris, about 23 K. from the Front.” [3]

The sound of guns was plainly audible; the signs of war were everywhere about. The station was almost wrecked—one end blown to atoms by a shell that had come through the roof. Everywhere were shell holes; among the tracks, in the platforms, and in the fields.… Houses everywhere were gaping ruins—roofs knocked off, holes in the walls, windows smashed. For, until the first Allied counteroffensive started, the enemy were within 4K. of the town. [4]

Entire route of Evacuation Hospital #3 in France, where Butler served, from St. Nazaire to Brest. Image: A Civilian in Uniform, b/t pp. 354 and 355.

That afternoon he and his comrades explored the devastated town; less than a week later, the hospital was moved to Château-Thierry and then Crezancy. Butler’s hospital formed part of the medical services supporting the first major American military action in the War. “The camp at Crezancy was the first at which the organization came face to face with all kinds of casualties straight from the front.” [5] His unit remained close to the fighting, treating the wounded of the many battles of the Meuse–Argonne offensive, up until the Armistice on November 11th that marked the War’s end. On that day, Butler wrote to his mother from behind the lines at Verdun:

Everyone is wild with joy! The war ended this morning at eleven. But it’s hard to realize. Automatically we camouflage our lights, but I don’t doubt will get out of that habit before long. . . . They had a big bonfire after supper [tonight] to celebrate with speeches, song, etc. . . . Now we are wondering what will happen to us. There is some talk of our going into Germany with the Army of Occupation, but we have as good chance of getting home fairly early. [6]

Home early was not to be: in December the unit moved north through Luxembourg to Trier, Germany. There it provided medical services for Allied soldiers held in a military prison hospital. For the first time, Butler noted the Spanish Flu in his war reminiscence:

Worn out by months of fighting, their resistance exhausted from the long march, hundreds fell easy prey to the virulent flu-pneumonia bug that was epidemic. While I was in charge of the pneumonia ward, of the 153 admissions, 50 died—one-third. A soldier would come in on his feet and be dead in 48 hours. The work was utterly frustrating. . . . [7]

Pages from Butler’s diary, which was written from July to December, 1918. Image: Charles Terry Butler papers, New York Academy of Medicine.

After four months, the unit was ordered home. It left Trier on March 27th and arrived in Brest, France, on the 31st, then embarked by ship on April 12th for Hoboken, arriving on the 20th. On April 27th, Butler was discharged from the military at Fort Dix. Between his volunteer service in 1916–1917, and his military service in 1917–1919, he had served over two years, or half of the war.

Charles Terry Butler in July 1975. Image: A Civilian in Uniform, p. 399.

After the war, Butler married, had children, and entered private practice, but by 1923 rheumatoid arthritis led him to retire. Moving to the Ojai Valley of Ventura County, California, he became a prominent civic and cultural leader. In 1975, after many years of work, he privately published A Civilian in Uniform as perhaps “the most complete account of one of the most active large mobile evacuation hospitals” in the First World War. Butler died in 1980.

Reading through A Civilian in Uniform one learns the reason for its writing: to combine the historical and the personal. Throughout the work, Butler mixed his letters and diary entries with understanding of the war and the official account of his hospital unit. He was justly proud of that unit:

This outfit, through trial and error and after many varying experiences in battle areas, had reached a state of efficiency in all departments that may have served as a useful guide for the structure and administration of evacuation hospitals in World War II. [8]

And of his role:

Yet when, from the multi-thousands of wounded who passed through the portals of these two hospitals, are sorted out the hundreds who owe much of their future physical well being to the professional performance of one single individual, and perhaps that man’s work during those years of bloodshed warrants, in philosophical perspective, a place a notch or two above the microscopic level. [9]

For many, the attraction of war may come from the desire to play a role in a venture of world-wide consequence. For Butler, this played out through his medical work in World War I.

The New York Academy of Medicine Library also houses Butler’s papers.

References:

[1] Charles Terry Butler, A Civilian in Uniform (Ojai, CA: “Private edition,” 1975).

[2] Butler was expected to outfit himself for his service, in the amount of $275.00 for uniforms, insignia, blankets, cots, and incidentals such as mirrors, electric lights, and candles. He received $2,000 a year in compensation, from which were deducted the premium for War Risk Insurance—life and disability insurance provided through the government—and $1.00 a day for officers’ mess! Butler, A Civilian in Uniform, 123–24.

[3] Butler, “Diary,” July 30, 1918, A Civilian in Uniform, p. 230.

[4] Butler, “Diary,” July 30, 1918, A Civilian in Uniform, pp. 230–31.

[5] Butler, A Civilian in Uniform, p. 248.

[6] Butler to “Mother” [Louise Collins Butler], November 11, 1918, in A Civilian in Uniform, pp. 312–13.

[7] Butler, A Civilian in Uniform, p. 332. There also Butler was assigned the task of writing the history of Evacuation Hospital #3, which formed much of the basis of A Civilian in Uniform.

[8] Butler, A Civilian in Uniform, p. 364.

[9] Butler, A Civilian in Uniform, p. 355–56.