By Becky Filner, Head of Cataloging

The New York Academy of Medicine Library is currently undertaking the cataloging of a collection of rare pamphlets from the 17th century through the early 20th century. Through this process, we’ve come across many fascinating (and sometimes perplexing) items. Here I will highlight four pamphlets from the 18th and 19th centuries that prescribe surprising cures for ailments.

In 1704, Nicolas Andry de Bois-Regard (1658-1742)[1], a French physician and writer, published a pamphlet in Paris, Le thé de l’Europe, in which he enumerates the health benefits of “Europe tea,” or Veronica officinalis (also known as speedwell or gypsyweed.) Our pamphlet, titled Preservatif contre les Fièvres Malignes, ou Le Thé de l’Europe et les Proprietez de la Veronique, is a 1710 edition of this work printed in Lyon. Andry recommends Veronica officinalis for treating headaches, sore throats, dry coughs, fevers, asthma, dysentery, and many other ailments. Speedwell is still used as a dietary supplement today, however its efficacy in treating any of these conditions is inconclusive.

The title page to Andry’s 1710 Lyon edition of Le Thé de l’Europe.

Engraving of Veronica officinalis from Andry’s Le Thé de l’Europe.

The second pamphlet, by John Andree (1697/8-1785)[2], a physician and co-founder of the London Hospital, recommends against using hemlock to treat cancer. Andree is responding to the Viennese physician Anton von Störck’s 1760 publication on hemlock, An Essay on the Medicinal Nature of Hemlock. In his Observations upon a Treatise on the Virtues of Hemlock, in the Cure of Cancers, Andree warns that when he tried to replicate Störck’s claims about hemlock, he found that “some curable Scirrhuses [tumors] were, during the Use of the Extract of Hemlock, instead of mending, brought to the State of deplorable Cancers.”[3] Not only is hemlock not a cure for cancer, it is “detrimental.”[4] Throughout the pamphlet, Andree provides specific details of the negative side effects his patients encountered while trying hemlock as a treatment. Andree is hopeful that new cures will be found for cancer, but he warns that “we should be cautious not to recommend any Thing before we are well assured of the Certainty of its Effects; nor publish Cases glossed over with a Design, perhaps, to raise our Reputation.”[5]

Title page from John Andree’s 1761 work, Observations upon a Treatise on the Virtues of Hemlock, in the Cure of Cancers.

The third pamphlet, Paul Bolmer’s New Receipts and Cures for Man & Beast (1831), is by far the strangest of the four pamphlets. Printed on cheap paper and apparently self-published (the cover reads, “Published by Paul Bolmer,” and the title page reads, “Printed for the Purchaser” where we would expect to see a printer or publisher’s name), this compilation of folk remedies is strikingly odd.[6] Bolmer’s cures include tea made of catnip for treating morning sickness, pills made of brown sugar and pepper for treating toothache, garlic juice mixed with whiskey and breast milk for treating colic in children, and a concoction of white oak bark, pennyroyal, knotgrass, whortleberries, and French brandy for curing dysentery. Many of the recipes have specific directions involving times of day or phases of the moon: a “certain cure for the tooth-ache” is to:

take a goose quill and cut it off where it begins to be hollow, then scrape off a little from each nail of the hands and feet, put it into the quill & stop it up, after which bore a hole towards the rise of the sun, into a tree that bears no fruit, put the quill with the scrapings of the nails into the hole and with three strokes close up the hole with a bung made of pine wood. It must be done on the first Friday in New moon in the morning.[7]

Paul Bolmer, in his New Receipts and Cures for Man & Beast (1831), compiles folk remedies that seem outlandish today.

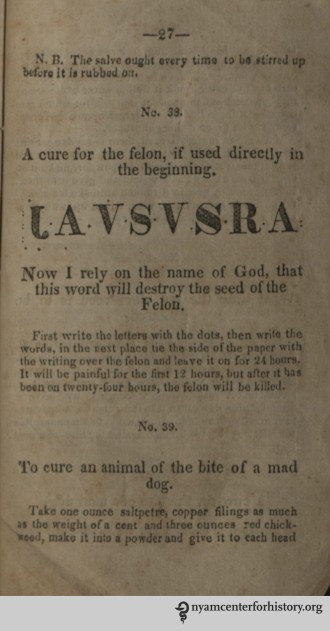

Bolmer’s “A cure for the felon” is perhaps the strangest moment in this weird pamphlet.

The most bizarre cure in this pamphlet is Bolmer’s “A cure for the felon, if used directly in the beginning” (see image of the page above.)[8] After writing the word “Javsvsra” (with the J backwards and dots specifically placed between and under the letters) and the phrase, “Now I rely on the name of God, that this word will destroy the seed of the Felon,” Bolmer promises that by “tie[ing] the side of the paper with the writing over the felon and leav[ing] it on for 24 hours . . . the felon will be killed.” It is hard to imagine that anyone ever believed this would work. Someone must have been buying what Bolmer was selling, however, because this book went through three German editions (1831, Philadelphia 1838, and Harrisburg, PA 1842), the 1831 English translation discussed here, and an English reprinting in 1853 in Greencastle, PA.[9]

The fourth pamphlet, The Boston Cooking School, 372 Boylston Street: Invalid Cookery: Nurses’ Course, was published in 1898 to accompany a Boston Cooking School class for nurses. Divided into six lessons, it covers beverages; beef tea, gruels, and mushes; eggs, toast, sandwiches, etc.; fish, jellies, etc.; soups; and desserts. Many of the recipes are familiar (oatmeal, omelets, toast), but others (Irish moss blanc mange, Junket custard, ivory jelly) use unfamiliar ingredients or simply do not suit our taste. The Library holds many related pamphlets and cookbooks about invalid cookery, a popular topic in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The front cover and the first page of The Boston Cooking School’s Nurses’ Course in Invalid Cookery.

As we continue to catalog our extensive rare pamphlet collection, we expect to uncover many more fascinating, illuminating, and downright weird pamphlets. Stay tuned!

References:

[1] For more information about Andry, see Remi Kohler. “Nicolas Andry de Bois-Regard (Lyon 1658-Paris 1742): the inventor of the word “orthopaedics” and the father of parasitology.” Journal of Children’s Orthopaedics. 2010 Aug.; 4(4): 349-355. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2908340/

[2] For more information about Andree, see D.D. Gibbs. “Andree, John (1697/8-1785).“ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press; 2004. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/514, accessed 2 Nov 2017.

[3] John Andree. Observations upon a Treatise on the Virtues of Hemlock, in the Cure of Cancers. London: J. Meres; 1761, p. iv.

[4] Ibid., p. vii.

[5] Ibid., p. vii.

[6] This pamphlet was apparently published in southern Pennsylvania, not Germany (as the title page notes.) This is an English translation of a pamphlet originally printed in German as Eine Sammlung von neuen Rezepten und erprobten Kuren fur Menschen und Thiere (Deustchland [i.e. Pennsylvania]: Gedruct fur den Kaufer, 1831.) Bolmer’s work may be plagiarized from Daniel Ballmer’s Eine Sammlung von neuen Recepten und bewahrten Curen fur Menschen und Vieh (Schellsburg, PA: Friedrich Goeb; 1827.) For further discussion of these pamphlets, see Christopher Hoolihan. An Annotated Catalogue of the Edward C. Atwater Collection of American Popular Medicine and Health Reform. Volume III. Rochester: University of Rochester Press; 2008, p. 79-80. Available through Google Books.

[7] Paul Bolmer. New Receipts and Cures for Man & Beast. Germany: Paul Bolmer; 1831, p. 12.

[8] Ibid., p. 27.

[9] This information about the various editions of this work is taken from Christopher Hoolihan’s An Annotated Catalogue of the Edward C. Atwater Collection of American Popular Medicine and Health Reform. Volume III. Rochester: University of Rochester Press; 2008, p. 80.