By Danielle Aloia, Special Projects Librarian

October is Domestic Violence Awareness Month, observed a month after the 20th anniversary of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA). VAWA was drafted in 1990 by then-Senator Joe Biden, who understood the devastating effects of domestic violence on women and children and the need for legislation. Congress took four years to approve the act, which was subsequently reauthorized in 2000, 2005, and 2013.

In honor of VAWA’s 20th Anniversary, the White House published the report 1 is 2 Many: Twenty Years of Fighting Violence Against Women, reminding us that: “In the name of every survivor who has suffered, of every child who has watched that suffering, the battle goes on; much remains to be done.” This statement seems even more relevant after the high-profile domestic abuse cases in the media recently.

Until the 1990s, laws weren’t enforced or guaranteed to protect women from their male abusers. In the past, domestic violence was thought to be a personal matter between the concerned parties. The legal system was reluctant to impinge on such a personal affair and if it did the punishment was less severe than for the assault of a stranger. Even though child abuse reporting laws were established in the late 60s, laws against the abuse of women weren’t in effect until the mid-70s.1

Several historical sources in our collection deal with domestic violence from long before the time of VAWA.

John Stuart Mill. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

In 1861, John Stuart Mill wrote The Subjection of Women, but didn’t publish it until 1869 because he didn’t believe it would be well received.2 He was a British philosopher and wrote very candidly about women’s equality. Today, he is seen as an inspiration for women’s liberation. Even though he touted equality for women, as in the quote below, he was still constrained by the times in which he lived. He wasn’t keen on women finding work outside of the home or having the same choices as men. But he did believe that women’s knowledge was just as important as a man’s.

“The principle which regulates the existing social relations between the two sexes—the legal subordination of one sex to the other—is wrong in itself, and now one of the chief hindrances to human improvement; and that it ought to be replaced by a principle of perfect equality, admitting no power or privilege on the one side, nor disability on the other.”3

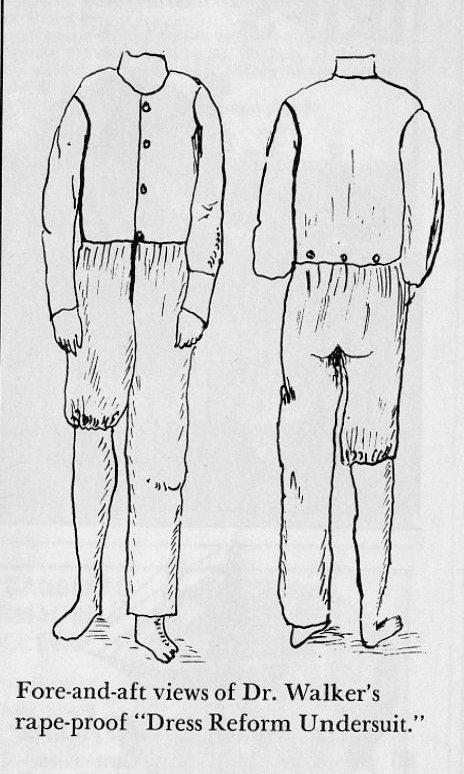

During this same time in the United States, Dr. Mary Walker was making news across the country for her activity in equal rights, especially in the Dress Reform Movement. She was the first woman to win the Congressional Medal of Honor for her medical work during the Civil War. She was later stripped of the title because of technicalities, but refused to give back the medal. The Honor was justly restored to her posthumously in 1977.4 She was seen as a rabble-rouser and was arrested on numerous occasions for wearing men’s clothing in public. She even designed a suit that would hinder the incidence of rape.

From: Lockwood, Allison. Pantsuited pioneer of women’s lib, Dr. Mary Walker. Smithsonian 1977;7(22):113-119.

In 1871 Dr. Walker wrote a book on women’s equality titled Hit. The title is a bit of an enigma and possibly has to do with her own unhappy marriage. This treatise asserts that women should be treated as equals under Constitutional law: “God has given to women just as defined and important rights of individuality, as HE has to man; and any man-made laws that deprive her of any rights or privileges, that are enjoyed by himself, are usurpations of power.”5

From: Lockwood, Allison. Pantsuited pioneer of women’s lib, Dr. Mary Walker. Smithsonian 1977;7(22):113-119

Hit discusses topics including love and marriage practices of various cultures, like Sicily, Syria, and Java; dress reform; divorce; and labor. Her chapter on tobacco is quite enlightening. She writes of the over-spending on tobacco products in New York City and the harm that smoke causes. “If all this $10,500,000 was expended in providing homes and food for the worthy poor, and unfortunately degraded women of New York, thousands of agonies would be relieved, and millions more prevented.” On alcohol consumption she boldly stated: “Every few weeks we read an account of a man killing his wife, or butchering his children while under the effects of the poison that our great Government derives such a large internal revenue.”6

From: Comstock, Elizabeth. Maude Glasgow, M.D. Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association 1953;8(1):26.

Another pioneer in women’s rights was Maude Glasgow, MD. She was also a pioneer in preventive medicine and public health in New York City in the early 20th century.7

Dr. Glasgow wrote the book Subjection of Women and Traditions of Men, which provides an historical perspective on the status of women throughout ages. Prehistoric times, she described, were considered the “Matriarchal Age” because women founded almost everything from tools to agriculture. The “Patriarchal State” that followed was “founded on property and physical force.” As women lost their sense of autonomy men gained and refused to relinquish control.8

“The literature of all ages is full of insults, diatribes and accusations against women, yet in spite of the prolific abuse he lavished on her, man apparently cannot stand even the most gentle censure no matter how well-founded, and tries to suppress everything drawing attention to any of his own shortcomings or blunders. His self-love and ideas of grandeur must be protected at all cost.”9

Domestic violence-related issues continue to loom large today. In a recent publication, the CDC reported that domestic violence is a serious public health problem with long-term consequences.10 Their prevention “strategy is focused on principles such as identifying ways to interrupt the development of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) perpetration; better understanding the factors that contribute to respectful relationships and protect against IPV; creating and evaluating new approaches to prevention; and building community capacity to implement strategies that are based on the best available evidence.

From: Breiding, M.J., Chen J., Black, M.C. Intimate Partner Violence in the United States — 2010. 2014. Click to enlarge.

We have to do better in fostering a society of zero tolerance, holding offenders accountable, and not blaming the victim.

References

1. California Department of Health Services. History of Battered Women’s Movement. Indiana Coalition Against Domestic Violence; 1999. Available at: http://www.icadvinc.org/what-is-domestic-violence/history-of-battered-womens-movement/#dobash. Accessed September 26, 2014.

2. California Department of Health Services.

3. Mill, John Stuart. The Subjection of Women. London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer; 1869. Available at: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/27083/27083-h/27083-h.htm.

4. Lockwood, Allison. Pantsuited pioneer of women’s lib, Dr. Mary Walker. Smithsonian 1977;7(22):113-119.

5. Walker, Mary E. Hit. New York: The American News Company; 1871.

6. Walker, Mary E.

7. Maude Glasgow, MD. American Medical Women’s Association; 2014. Available at: https://www.amwa-doc.org/faces/maude-glasgow-md/. Accessed October 9, 2014.

8. Glasgow, Maude. The Subjection of Women and Traditions of Men. New York: M. I. Glasgow; 1940.

9. Glasgow, Maude.

10. Breiding, M.J., Chen J., Black, M.C. Intimate Partner Violence in the United States — 2010. 2014. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/cdc_nisvs_ipv_report_2013_v17_single_a.pdf

Pingback: Women, Equality, and Justice | Nature, Art, and Literary Musings

Amazing! Thank you for this information. I had never heard of either Dr. Mary Walker or Dr. Maude Comstock before. I bought Walker’s book for Kindle and put Comstock’s on my Amazon wish list. It’s amazing how little historical notice either of them receives, and yet both were obviously highly educated. I am currently reading John Stuart Mill’s “Subjection of Woman” and will be interested in comparing that with Comstock’s book. The Comstock quote is priceless! I wish the book were available for Kindle.

Pingback: Did Corsets Harm Women’s Health? | Books, Health and History