by Anthony Murisco, Public Engagement Librarian

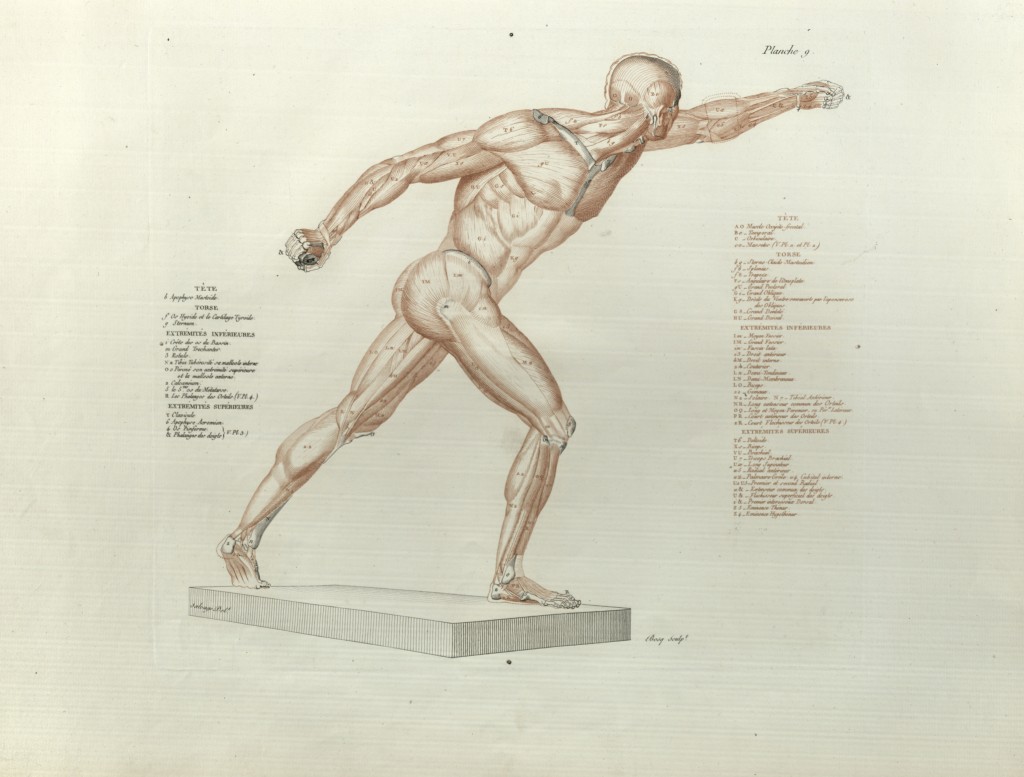

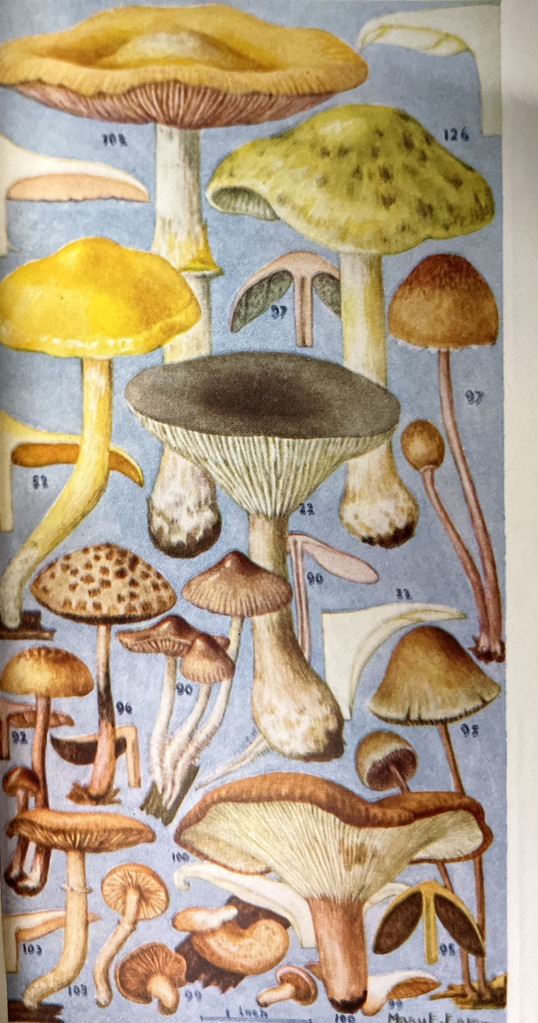

Each year, the New York Academy of Medicine Library is proud to host visits from students across all different disciplines. From graduating medical students to those studying the culinary arts, the history of public health is surprisingly encompassing and intertwined. Our Historical Collections Librarian, Arlene Shaner, chooses different materials for each group visit. She considers who is coming, what they are studying, and what they might like to see. The display that Arlene curates for the visitors reflects how they might want to use the collection for their work. These displays include not just books but posters, pamphlets, and other assorted ephemera.

In a previous guest post, Dr. Evelyn Rynkiewicz, Assistant Professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology, shared why she enjoys bringing her “Disease Ecology in a Changing World” class to the library. While teaching design and business students at FIT, she hopes to instill science literacy and curiosity within them. At the end of the course, they are assigned creative research projects. The students choose a disease to study and make their own unique presentation to help inform the public.

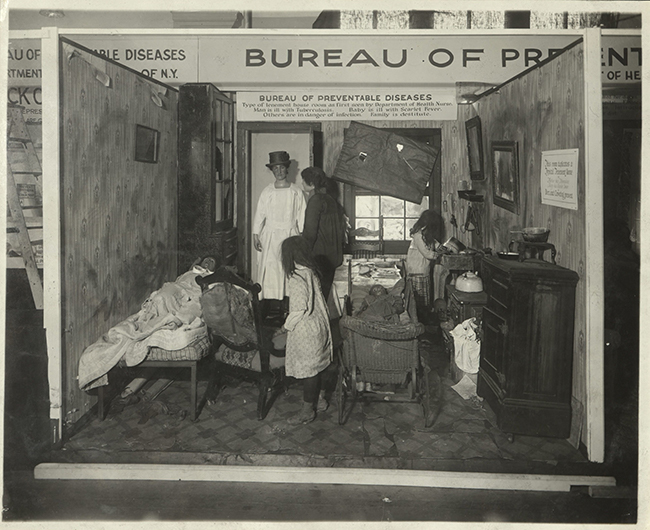

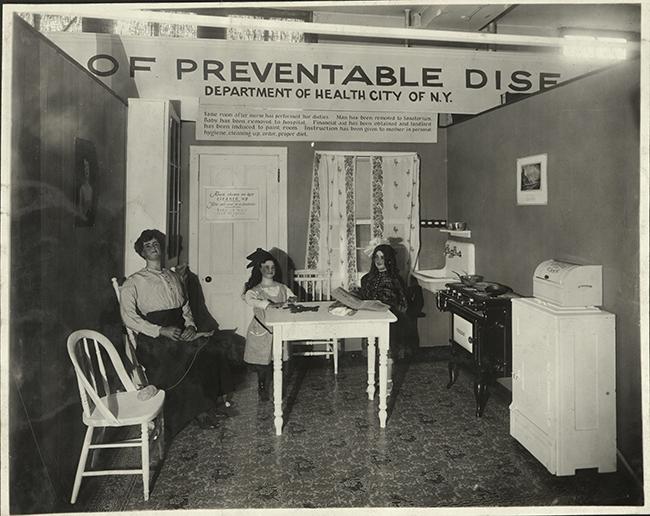

We are excited to once again present submissions from Dr. Rynkiewicz’s class, which visited the Library on October 24th, 2023. We also present images, some items from our own collection, others from elsewhere, that may have sparked their imagination for this project. While we would love to include all the submissions that we received, we are limited to what we can show on a blog post. If there happens to be a student art show in your area, you should check it out. You never know what you are going to see!

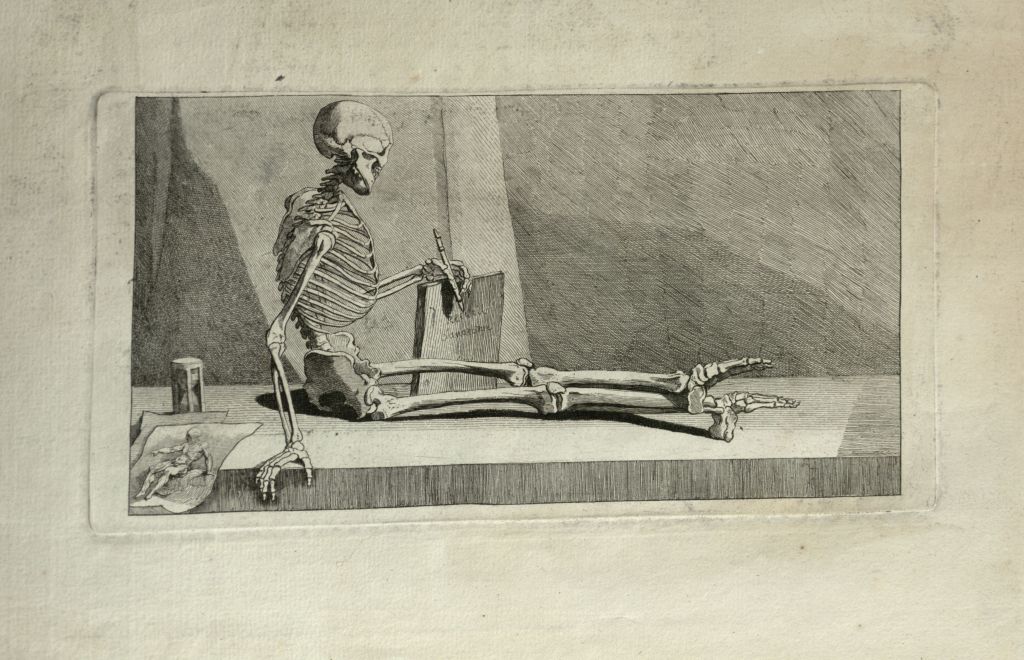

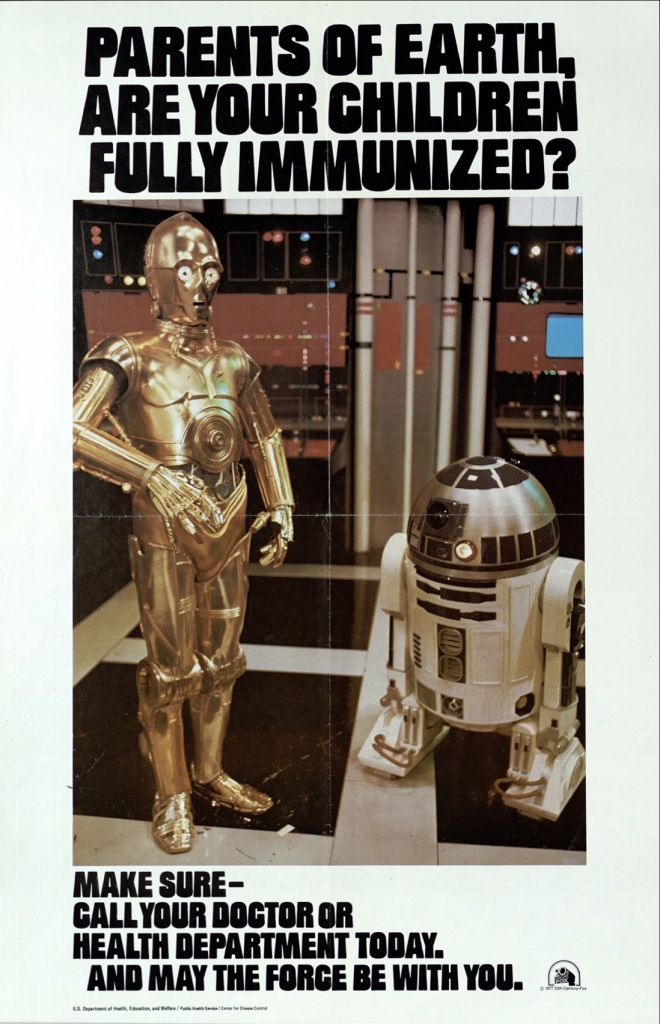

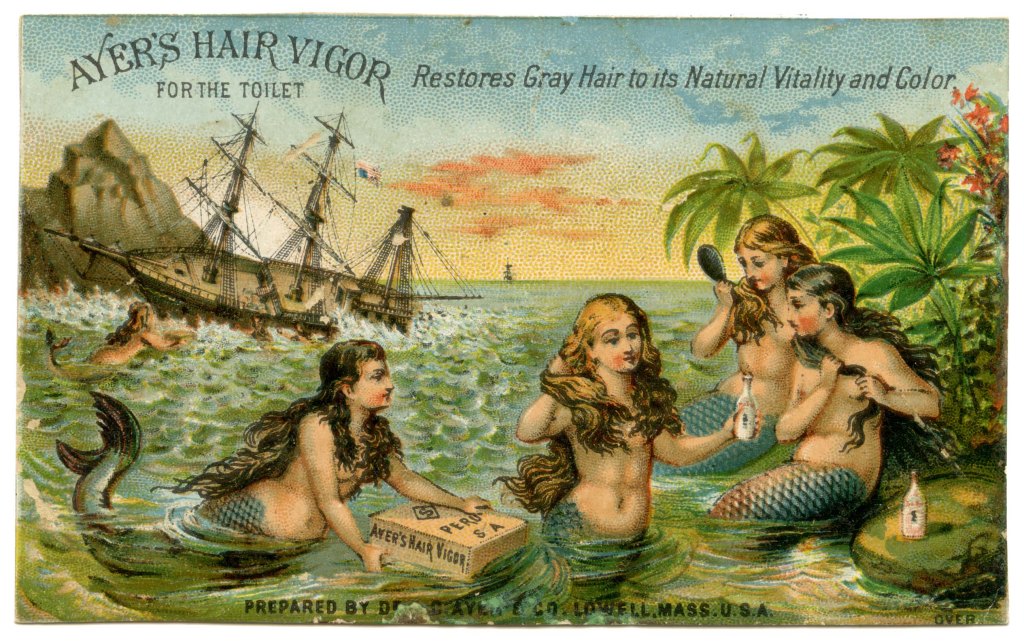

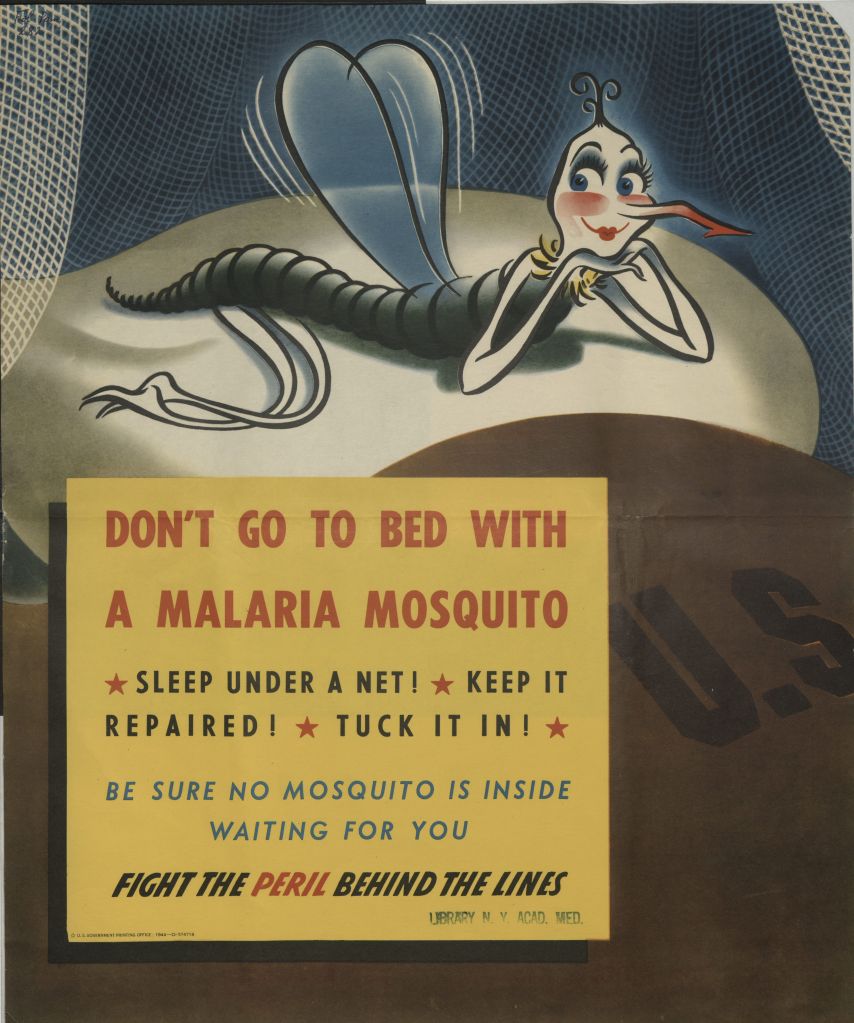

Alluring pictures can draw lots of attention. An image can tell a story without the need to read the words attached. We live in a globalized society where visual signs speak louder than the written word. This is a bit of the thought process behind any kind of campaign, public health especially. We still see these kinds of efforts today!

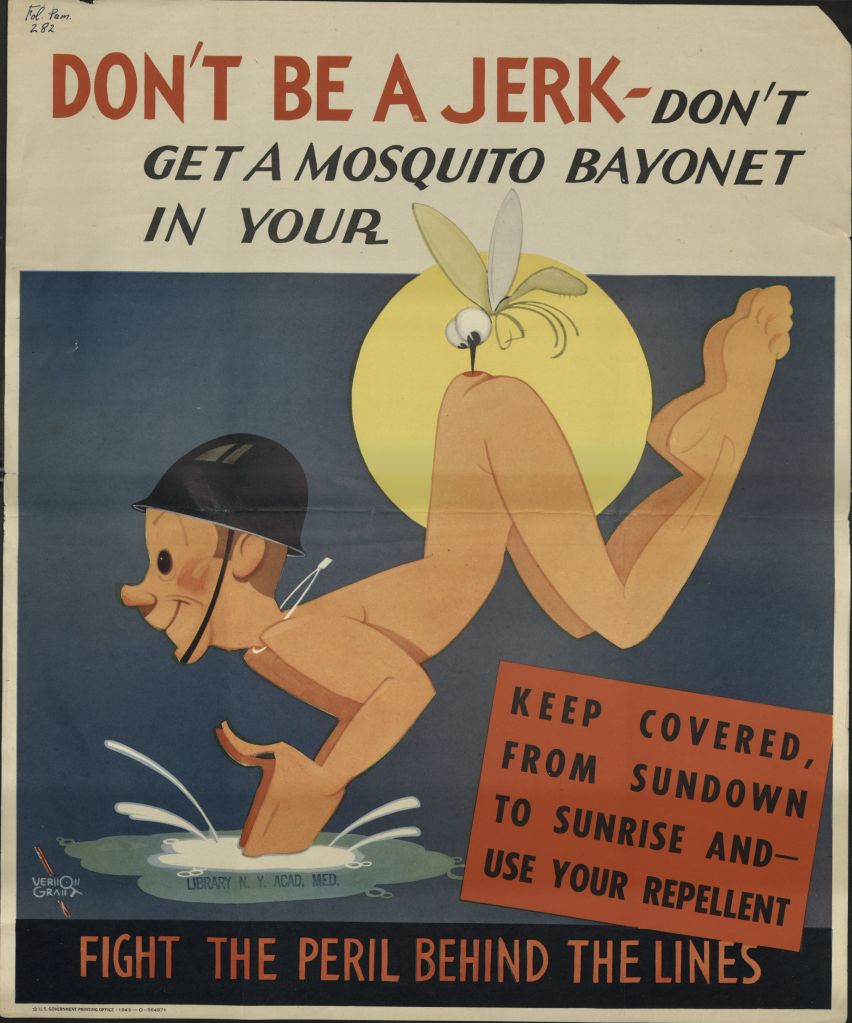

Theodore Geissel, in his pre “doctor” days, helped bring public service announcements to life in these posters. You could tell from his unique artistry that he was a gifted storyteller. These pictures were not only eye-catching but served an important purpose. This poster comes from a series directed towards soldiers fighting overseas during World War II that were designed by different artists.

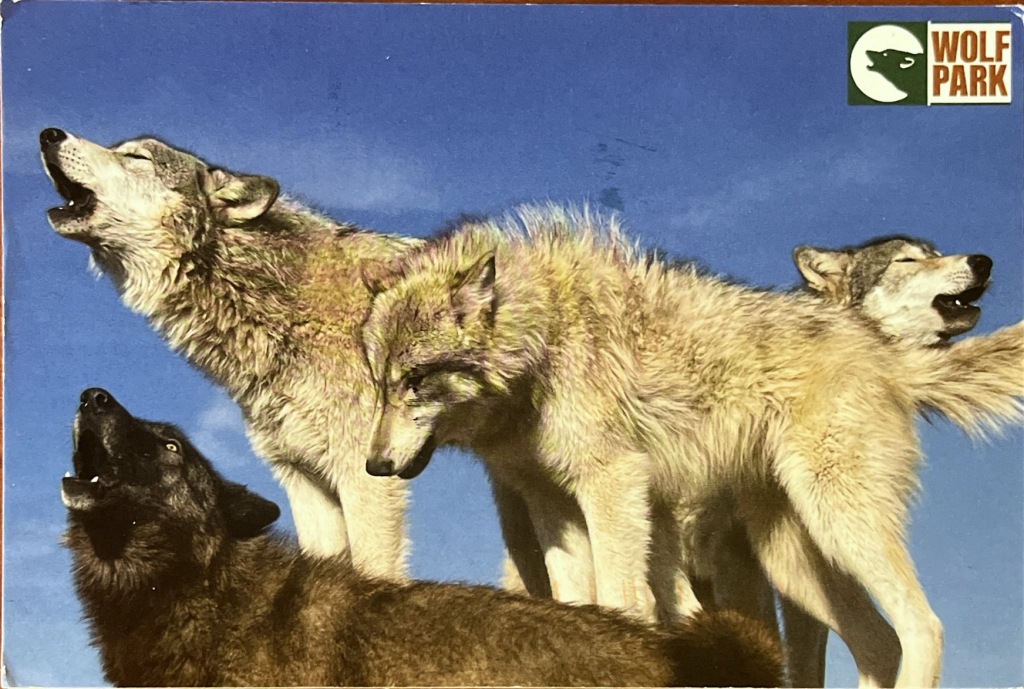

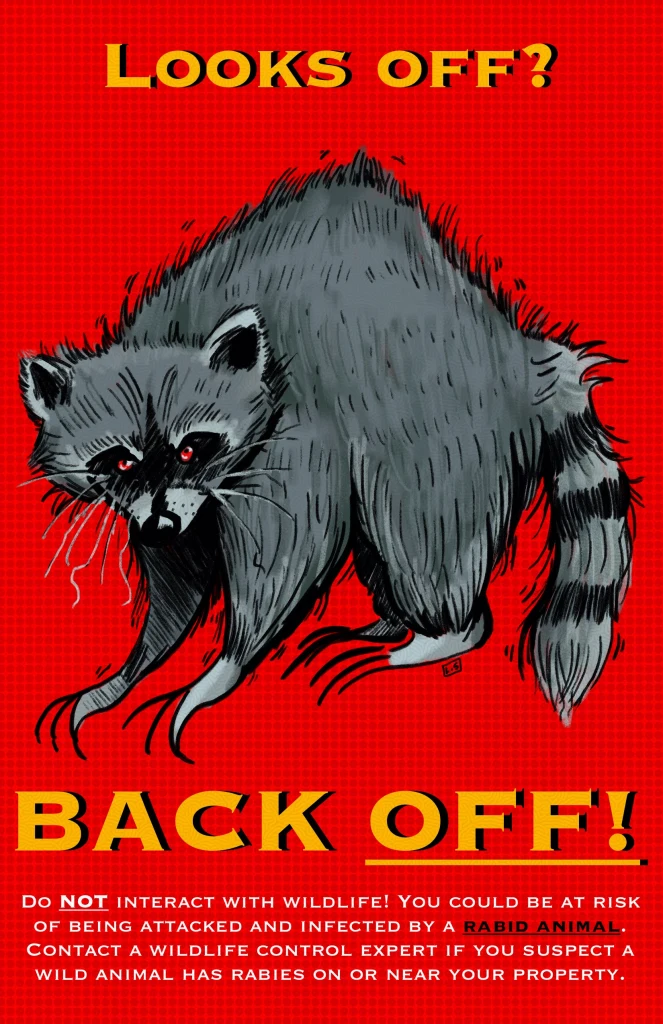

Just by looking at Laelani Sawicki’s (second year, Illustration major) poster for rabies, you can guess where it’s going…

Cordyceps have gotten a bad rep lately. Fear not, The Last of Us viewers! In Jada Arroyo’s (second year, Illustration major) poster set, their misconception is cleared up.

These public health posters were even allowed to get away with raunchier, more risqué content! Vernon Grant, creator of Rice Krispies’ Snap, Crackle, and Pop, made this poster for part of the same malaria prevention campaign.

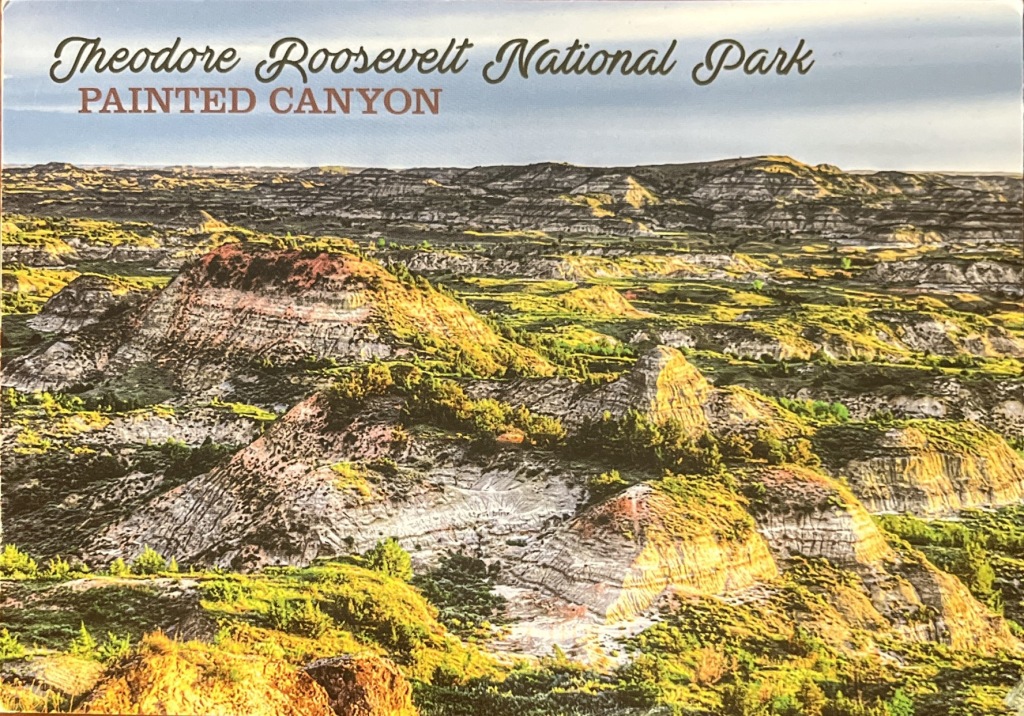

To convey the importance of recognizing chronic wasting syndrome in wild game, Amaryllis Arroyo (second year, Illustration) went with their own provocative image.

Fashion and activism reached a pinnacle with the yellow Livestrong bracelets of the mid-2000’s. You couldn’t go anywhere without seeing them, despite little marketing. The slogan itself, “Live Strong,” said all one needed to know. So simple and yet, so fashionable.

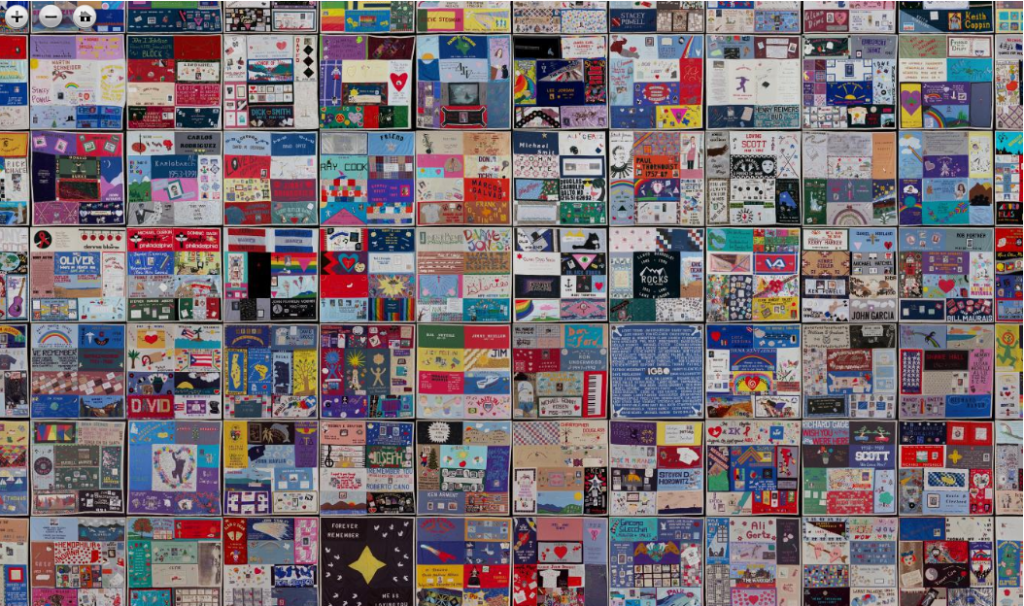

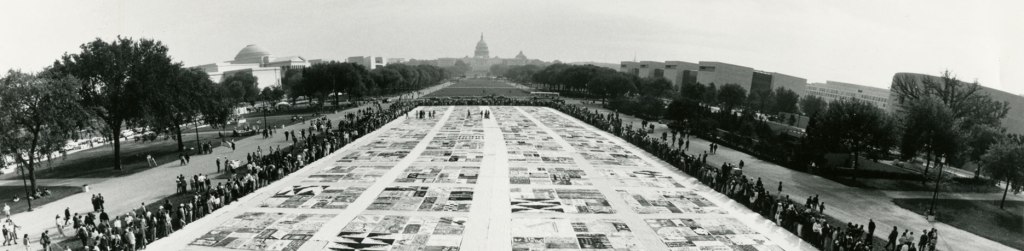

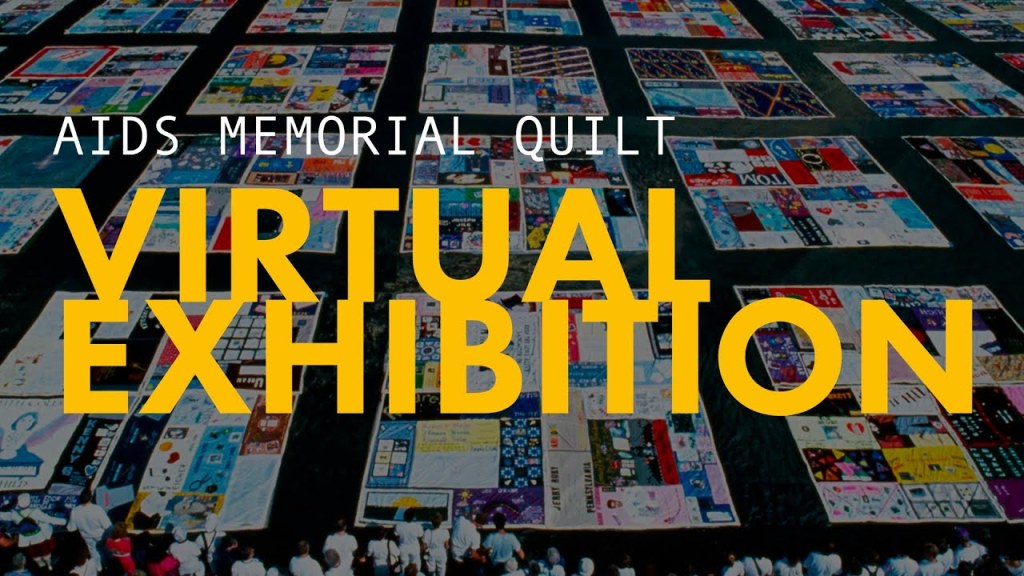

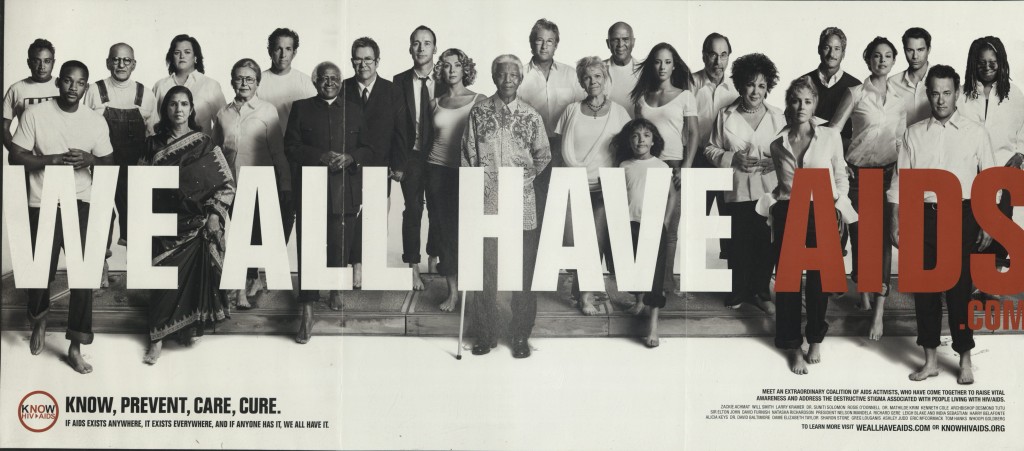

Kenneth Cole created a provocative ad campaign in 2005 called “We All Have AIDS.” The ads promoted a T-shirt, where all sales proceeds would be donated to fight the AIDS epidemic. Cole’s idea for the campaign came from the idea of “solidarity.” It was to ease the stigma surrounding the disease and fight preconceived notions. To fight the disease, physically and socially, we would all have to come together.

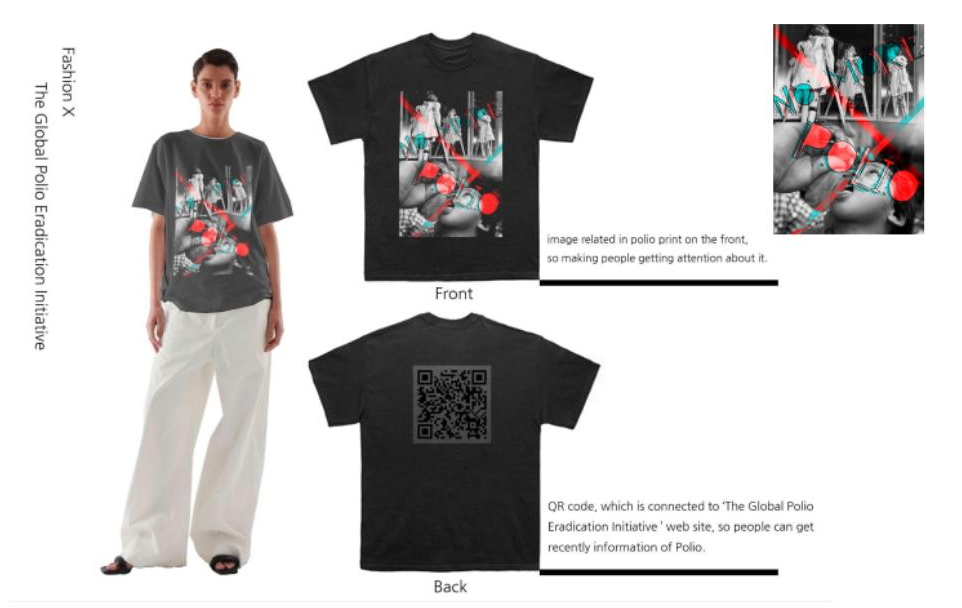

Students Chaea Im (first year, Fashion Design major) and Kylie Smith (first year, Fashion Marketing major) used tees as their canvas.

Chaea (above) focused efforts on polio awareness while Kylie (below) speaks on the lack of access for worldwide rabies vaccination.

Haute couture can also be used to convey a message. Alexander McQueen even referenced Charles Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species” on his 2009 runway! The models were fitted with heels based on an armadillo, gifting us the “armadillo heel.”

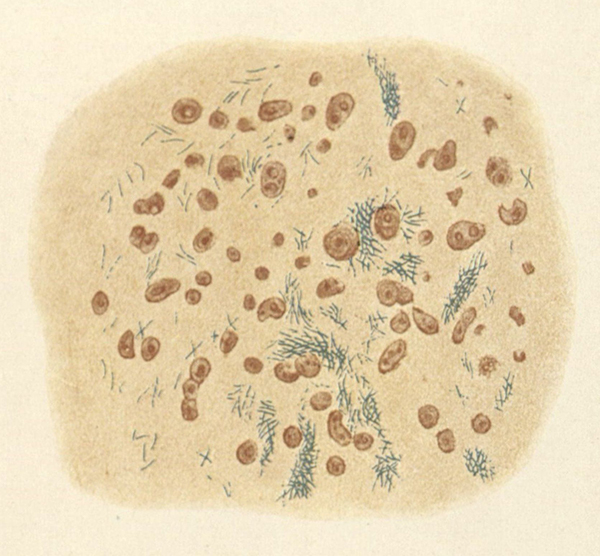

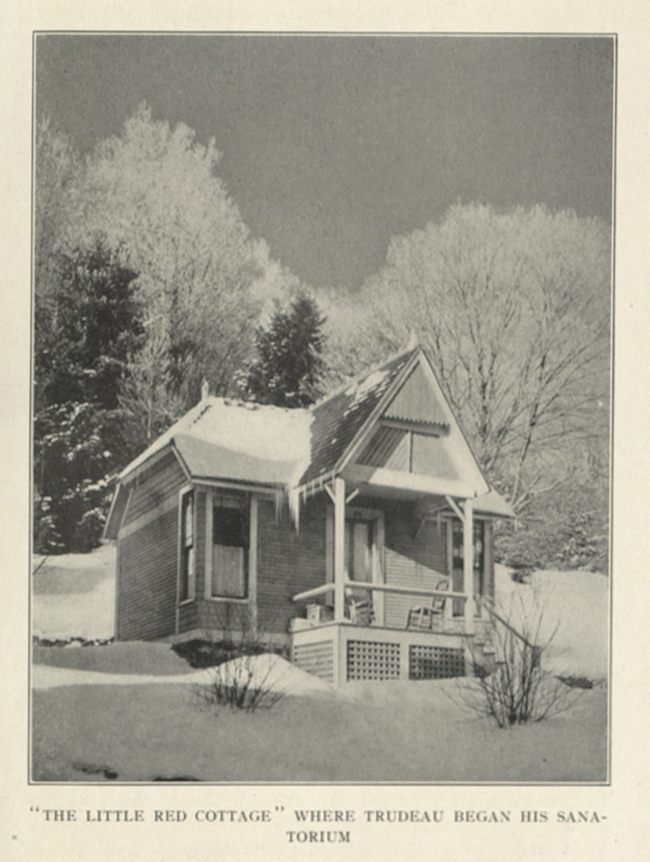

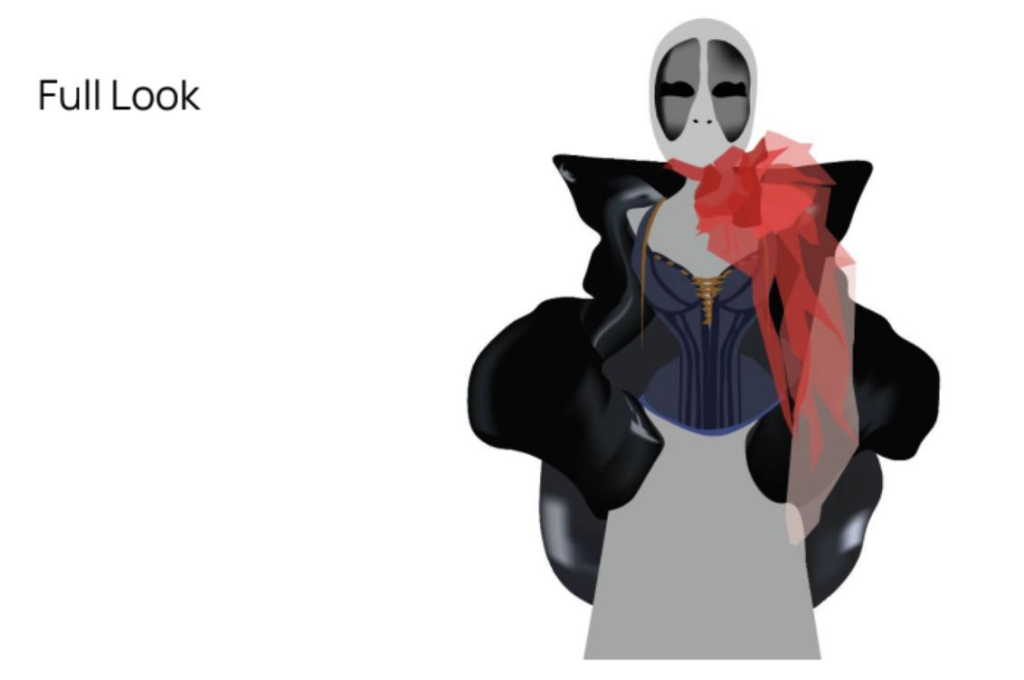

To convey information about tuberculosis through fashion, Charlie Sue Birznieks (third year, Communications Design major) mocked up garments to echo the physical effects of this respiratory bacterial infection. It takes form through a “blood choker, bone crushing corset, suffocating puffer jacket, and full-face respirator mask.”

The biggest way information, and unfortunately, disinformation, disseminates these days is through the internet. We can combat the negative by being sure to amplify knowledge from verified and reputable sources. Some of us may remember infographics shared during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

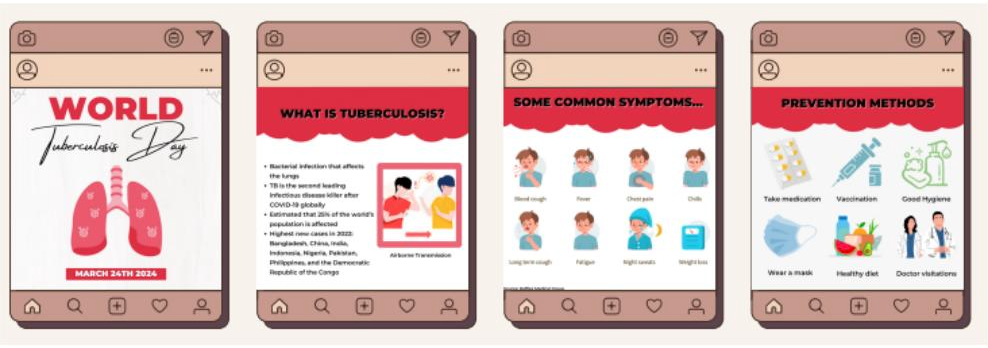

This project by Valerie See (fourth year, Cosmetics and Fragrance Marketing major) breaks down important information to share during World Tuberculosis Day. These images would go a long way to spreading awareness while linking back to a credible source.

That does not mean we shouldn’t share our own, lived experiences! There’s a great deal to learn from first-hand accounts. Audrey Cahill (second year, Illustration major) shows us what a social media timeline might have looked like in the 14th century during the time of the plague!

We once again thank Dr. Rynkiewicz and her students for allowing us to share their work. If you are interested in bringing your own class, please reach out to library@nyam.org.

References:

“About the Exhibition.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://blog.metmuseum.org/alexandermcqueen/about/ Accessed 27 March 2024.

Rynkiewicz, Dr. Evelyn. “FIT Visits the NYAM Library.” Books, Health, and History, 13 Apr 2023, https://nyamcenterforhistory.org/2023/04/13/fit-visits-the-nyam-library/. Accessed 27 March 2024.

Wilson, Eric. “From Kenneth Cole, A New Solidarity.” The New York Times, 1 Dec 2005, https://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/01/fashion/thursdaystyles/from-kenneth-cole-a-new-solidarity.html. Accessed 27 March 2024.