By Sean Purcell, The Media School, Indiana University-Bloomington and the Library’s 2023 Helfand Fellow

Mr. Purcell completed his Fellowship residency in the summer of 2023 and will present his research by Zoom on Thursday, December 7 at 4 p.m. (EST). To attend his talk, “A Portrait of Tuberculosis (as a Young Microbe): Representing Consumption at the Turn of the Twentieth Century,” register through NYAM’s Events page.

I spent a month over the spring and summer looking through the New York Academy of Medicine Library collections, working towards a mixed methods dissertation, titled The Tuberculosis Specimen: The Dying Body and its Use in the War Against the “Great White Plague.” I came to the library with an interest in the visual culture surrounding tuberculosis at the turn of the twentieth century, and in my research, I have cast a wide net, looking at an array of images, from doctors’ portraits to children at play, from histological samples to photographs of wet specimens.

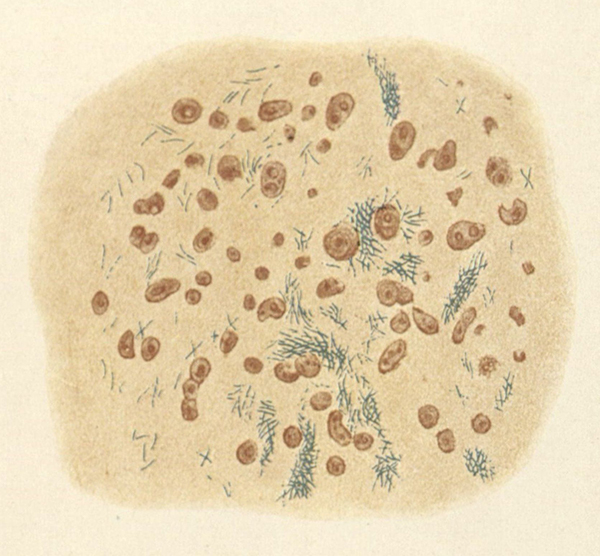

The turn of the twentieth century saw major shifts in the public, professional, and governmental interventions against tuberculosis. Robert Koch’s 1882 essay on the microbial cause of the disease led to a broad shift in how medical professionals and the lay public understood and combatted the disease. Koch had figured out a process to isolate the bacteria in laboratory animals and used a series of chemical baths to stain Mycobacterium tuberculosis a bright blue (fig. 1). Seeing the bacteria clear as day under the microscope helped move germ theory forward, and forced doctors and health worker to reconsider how to treat a disease that was, prior to Koch’s essay, considered a constitutional malady. The period after Koch’s essay saw the rise of public health interventions against the disease and the popularization of the tuberculosis sanatorium.

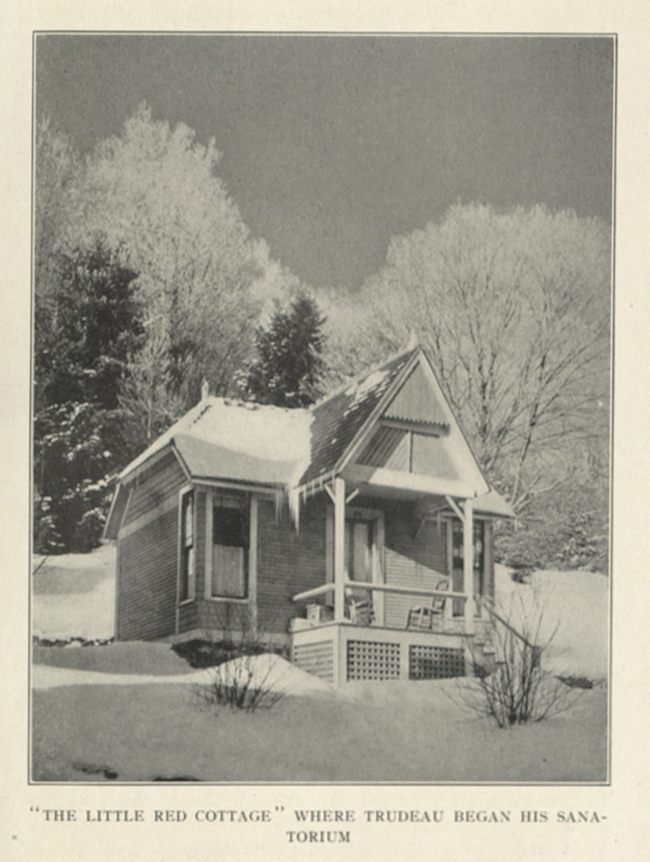

The most influential figure in the burgeoning sanatorium movement was Edward Livingston Trudeau. A doctor who had sought a cure for his own tuberculosis in upstate New York, Trudeau built his own laboratory and sanatorium, the Adirondack Cottage Sanatorium, in 1880 (figs. 2 & 3). This institution became a central fixture in the decades to come, as it was equipped with research facilities, and published its public-facing journal for tuberculous patients, The Journal of Outdoor Life.

While Trudeau’s sanatorium was the most prominent institution, it was far from the only one. Many for-profit institutions opened their doors during this period, in addition to the development of publicly funded sanitaria in certain states. Assisting the larger, long-term treatment facilities, some cities and hospitals adopted a dispensary system, where tuberculous patients could get assistance and medicine within an urban space.

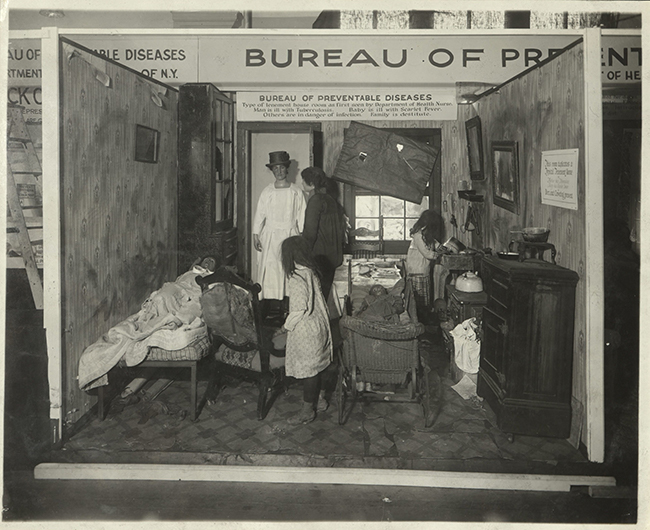

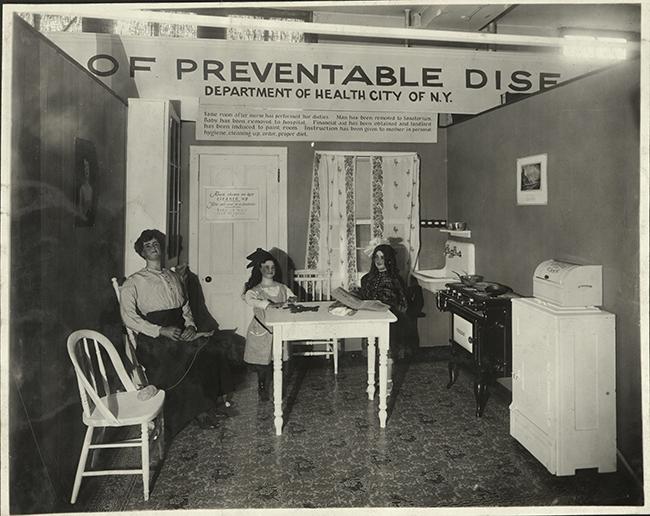

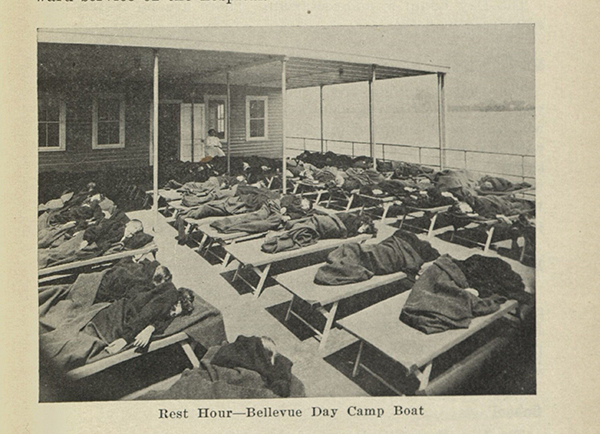

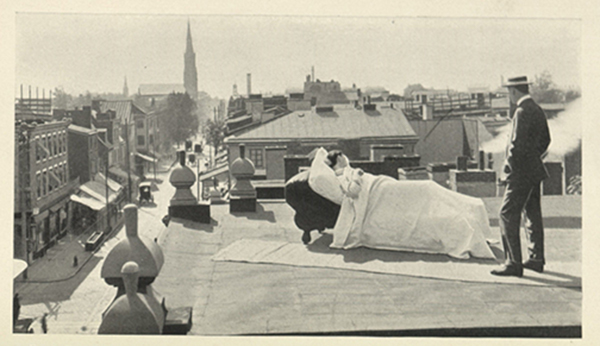

These dispensaries served patients, but also sought to teach the urban poor lessons on hygiene. Doctors and public health workers reeled at the dusty, ill kept living conditions of the urban poor, and argued that improper sputum management, poor ventilation, and dark living conditions were contributing to tuberculosis infections in American cities (figs. 4 & 5). While ideas regarding the “healing air” of a specific environment were becoming out of fashion for tuberculosis practitioners in the early 1900’s, most doctors argued that tuberculous patients should get away from the polluted and uncirculated air common to urban environments (figs. 6 & 7).

The fight against tuberculosis in this period saw a collection of different interventions, and the New York Academy of Medicine’s library offers a unique glimpse into the work of scientists and medical professionals who were trying to fight the disease. My time here as a Helfand fellow has been a boon to this research because of the library’s extensive collections, much of which has not been digitized.

References:

Feldberg, Georgina D. Disease and Class: Tuberculosis and the Shaping of Modern North American Society. (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1995).

Koch, Robert. “Aetiology of Tuberculosis.” Translated by T. Saure. Transactions of the Massachusetts Medical Association. (New York: William R. Jenkins, 1890).

Koch, Robert. “Die Ätiologie der Tuberculose.” In Gesammelte Werke von Robert Koch, 1:446–54, 467–565. (Leipzig: Verlag Von Georg Thieme, 1912).