A note from the Center for the History of Medicine & Public Health: This is the last post in Morbid Anatomy‘s guest series leading up to our Festival of Medical History and the Arts. If you’ve enjoyed these posts as much as we have, don’t despair! Tomorrow’s event holds a full day of lectures and activities from Morbid Anatomy, Lawrence Weschler, and the Center. We hope you can make it! See the full schedule here.

The NYAM rare book collection holds a gorgeous copy of the first French edition of Alexander Monro’s (1697–1767) celebrated Traité d’ostéologie … (or “Anatomy of Bones”). Monro was trained in London, Paris, and Leiden before going on to become the first professor of anatomy at the newly established University of Edinburgh. It was under his leadership, and that of his successors, that the school went on to become a renowned center of medical learning.

The NYAM rare book collection holds a gorgeous copy of the first French edition of Alexander Monro’s (1697–1767) celebrated Traité d’ostéologie … (or “Anatomy of Bones”). Monro was trained in London, Paris, and Leiden before going on to become the first professor of anatomy at the newly established University of Edinburgh. It was under his leadership, and that of his successors, that the school went on to become a renowned center of medical learning.

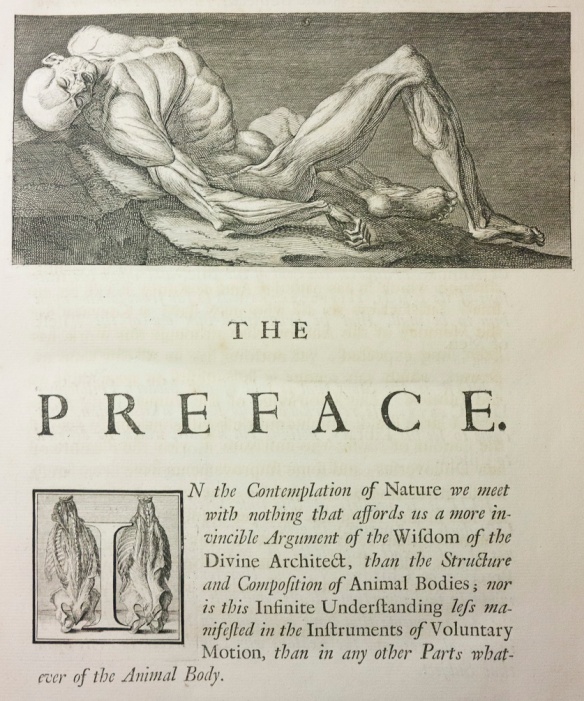

Monro originally published this book without images, thinking them unnecessary after William Cheselden’s lavishly heavily-illustrated Osteographia, or the anatomy of the bones of 1733 (more on that book at this recent post). The very fine copperplates you see here were added to the French edition by its translator, the anatomist Jean-Joseph Sue (1710–1792).

My favorite image in the book is a kind of memento mori–themed tableau morte of winsome, scythe-bearing fetal skeletons enigmatically arranged in a funereal landscape (images 1–3). I also love the frontispiece in which a group of plump putti proffer anatomical atlases and dissecting tools under the oversight of a skeletal bird (above).

- Monro 1

- Monro 2

- Monro 3

- Monro 4

- Monro 5

- Monro 6

- Monro 7

- Monro 8

- Monro 9

This post was written by Joanna Ebenstein of the Morbid Anatomy blog, library and event series; click here to find out more. All images are my own, photographed at the New York Academy of Medicine.