By Emily Miranker, Events & Projects Manager

The marvelous thing about libraries (well, one on an infinite list of marvels…) are the remarkable rabbit holes of investigation and imagination you fall into. Recently, I ran into a kitchen staple in an old medicine book:

Black Pepper is a remedy I value very highly. As a gastric stimulant it certainly has no superior…

Black pepper as a cure for anything, except perhaps bland food, was news to me. The above passage comes from the 19th century John Milton Scudder’s 1870 book Specific medication and specific medicines. In the 19th century “specific medicine” referred to a branch of American medicine, eclectic medicine, that relied on noninvasive practices such as botanical remedies or physical therapy.[i] As an eclectic practitioner, Scudder’s work was not mainstream, regular medicine, so I wondered if perhaps that was why pepper should come up as a remedy. Surely, pepper only belongs in the pantry not the medicine cabinet. But doing more research, it turns out that black pepper, Piper nigrum, originally from India, has been used by people for medicinal purposes for centuries.

A member of the Piperaceae family of plants, black pepper is a tropical vine. Its berries (the dried berries are the peppercorns we’re familiar with from the kitchen), were known to the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans long before it became one of the most sought-after spices in Europe during the Age of Exploration, the 15th-18th centuries. Depending on when it’s harvested, a vine produces four kinds of peppercorn. Green peppercorns are unripe berries that are freeze-dried. White pepper is almost ripened, the berries are harvested and soaked in water which washes off the husk leaving the gray-white seed. Red peppercorns are fresh, ripe berries. Black peppercorns are harvested when the spike of berries is midway ripe; these unripe berries are actually more flavorful than a fully ripe berry. The black peppercorns are blanched or left to ferment a few days and then dried in the sun. The drying process turns the husk black.[ii]

A detail of a page of recipes calling for pepper by the Roman gourmand Apicius, the oldest cookbook in West. Author’s favorite: #31 Oenogarum in Tubera, a wine sauce for truffle mushrooms calling for pepper, lovage, coriander, rue, broth, honey and oil.

Pepper came to the tables and pharmacies of Europe via trade from the west coast of India. It was coveted enough to be part of the ransom demand Alaric the Goth made of Rome when he invaded in 408 C.E.[iii] With its strategic location on the Adriatic, Venice dominated the spice trade in Europe in the Middle Ages. The Portuguese were the first to break the Venetian hold by finding an all-ocean route to India. By the 17th century the Dutch and English were players in the spice trade. Innocuous-seeming dark grains in shakers on tabletops now, pepper was once more valuable than silver and gold. Sailors were paid in pepper. The spice was also used for paying taxes, custom duties, and dowries.[iv] In their quest for pepper, among other spices such as cinnamon, cloves, and nutmeg, the Europeans brutally pursued spice monopolies regardless of the upheaval and violence they wrought on the peoples of India, Sumatra and Java.

Dating back to 6,000 B.C.E. the Materia medica of Ayurveda advocates using pepper for a number of different maladies, especially those of the gastrointestinal tract.[v] To this day in India, a mixture of black pepper, long pepper, and ginger, known as trikatu, is a common Ayurvedic medicinal prescription. Trikatu is a Sanskrit word meaning “three acrids.” In the Ayurvedic tradition “the three acrids collectively act as ‘kapha-vatta-pitta-haratwam’ which means ‘correctors of the three doshas of the human.’”[vi] Doshas are energy centers in the body in the Ayurvedic tradition.

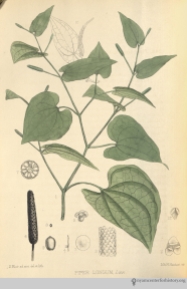

Pepper figured in Western medicine from antiquity onwards as well. Writing in the 7th century, Byzantine Greek physician Paul of Aegina quotes the 2nd-century Greek Galen on pepper’s’ medical properties, “it is strongly calefacient and desiccative.”[vii] Warming and drying, thus very good for stomach problems in his estimation. Side note: Galen’s office was in the spice quarter of Rome, underscoring the connections between health, spices, and food. Peppers’ use as a “gastric stimulant” persisted through the centuries. In our collection’s The elements of materia medica and therapeutics (1872), Jonathan Pereira states pepper “is a useful addition to difficult-to-digest foods, as fatty and mucilaginous matters, especially in persons subject to stomach complaints.” The illustrations of pepper plants in this post come from Robert Bentley’s Medicinal Plants (1880) which includes their medical properties and uses along with descriptions of habitats and composition.

Scientific studies on pepper coalesce around its compound piperine. The stronger—more pungent—the pepper, the more piperine it contains. The argument of studies on pepper’s properties is that adding pepper to a concoction increases its efficacy and digestibility. Research suggests “this bioavailability enhancing property of pepper to its main alkaloid, piperine…. The proposed mechanism for the increased bioavailability of drugs co-administered with piperine is attributed to the interaction of piperine with enzymes that participate in drug metabolism.”[viii]

I hadn’t looked to black pepper for any health benefits. I look to it for that delicious heat and spicy pungency it brings to my meals. But that’s the great thing about researching in our library; you always find delights beyond what you’re looking for.

References

[i] Eclectic Medicine. https://lloydlibrary.org/research/archives/eclectic-medicine/ Copyright 2008. Accessed August 30, 2018.

[ii] Sarah Lohman. Eight Flavors: The Untold Story of American Cuisine. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016.

[iii] Majorie Schaffer. Pepper: A History of the World’s Most Influential Spice. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2013.

[iv] Schaffer. Pepper. 2013.

[v] Muhammed Majeed and L. Prakash. “The Medicinal Uses of Pepper.” International Pepper News. 2000. Vol. 25, pp. 23-31.

[vi] Majeed & Prakash. 26.

[vii] Paulus Aegineta. La Chirurgie. Lyons: 1542.

[viii] Majeed & Prakash. 28.