T he New York Academy of Medicine hosted the 18th International Conference on Grey Literature: Leveraging Diversity in Grey Literature (GL18) on November 28 – 29, 2016. The Academy received a professional development grant from the National Network of Libraries of Medicine (NN/LM) to help support attendance at the conference. Five grant awardees, students and information professionals, were chosen to attend the conference for one or both days. Post-event, the awardees stated that the conference had a remarkable impact on their understanding of grey literature.

he New York Academy of Medicine hosted the 18th International Conference on Grey Literature: Leveraging Diversity in Grey Literature (GL18) on November 28 – 29, 2016. The Academy received a professional development grant from the National Network of Libraries of Medicine (NN/LM) to help support attendance at the conference. Five grant awardees, students and information professionals, were chosen to attend the conference for one or both days. Post-event, the awardees stated that the conference had a remarkable impact on their understanding of grey literature.

In their own words, awardees describe their experience at the GL18 conference:

Jennifer Kaari

Library Manager | Mount Sinai

I was interested in attending the 18th International Conference on Grey Literature because like so many librarians, I often find that grey literature is a missing piece of the research process. I was struck during the conference by how apt diversity was a theme for a grey literature conference. Grey literature is a wildly diverse arena, from the many formats and publication types that fall under the umbrella to the wide range of fields that generate and use grey literature. Many of these were represented in the conference, from the law to nuclear science to community initiatives.

As highlighted by the presentations on the Indigenous Law Portal and LGBT communities, grey literature can also give a voice to communities that may be left out of traditional scholarly publishing. I came away with the understanding that leveraging grey literature is essential to ensuring that these voices are included in research and the policy decisions that result.

Perhaps most importantly for my personal development, I left the conference with a bright new idea about a topic in grey literature to research in the upcoming year. I’m looking forward to attending future conferences- hopefully as a speaker! Thanks to the NN/LM for this wonderful opportunity.

Sharon Whitfield

Emerging Technologies Librarian | Cooper Medical School of Rowan University

The 2016 Grey Literature conference, titled Leveraging Diversity, had at least one presentation of interest to everyone. The presentation topics ranged from open access to LGBT+.

As this was my first GreyLit conference, I was surprised to find a very welcoming community of researchers, librarians and professionals who all were invested in researching, reporting and making grey literature accessible. During the first day, I found the presentations inspiring. The presentation showed how grey literature impacted the various constituencies at each institution and the importance of making the literature available to the populations.

On the second day, the conference had more of a practical application by addressing open access and researchers’ needs. An example was the Data Science Panel. The Data Science panel, which included two librarians and a researcher, addressed research needs that are occurring at my own institution. The panel provided new technologies that I am currently exploring for institutional adoption. Yet, it was hearing the importance of access to grey literature and datasets by the researcher, which really help me to understand the role the library should be playing to support researchers at my own institution.

Poster session at GL18. Photo by Danielle Aloia.

Cheryl Branche, MD, MLS

P/T Adjunct Reference Librarian | Health Professions Library Hunter College, CUNY Brookdale Campus

On Tuesday, November 29, I viewed the engaging poster presentations and discussed the posters with the presenters, who hailed from France, Italy, Japan, Korea, The Netherlands, and the United States. Three posters interested me:

- Policy Development for Grey Literature Resources: An Assessment of the Pisa Declaration

- Grey Literature in Transfer Pricing: Japan and Korea

- WorldWideScience.org: An International Partnership to Improve Access to Scientific and Technical Information and Research Data.

During the Tuesday afternoon session, Debbie Rabina presented an ongoing long-term study, which identified the information needs of incarcerated people and demonstrated their willingness to write to agencies for information. The late afternoon session included a presentation entitled: The GreyLit Report: Understanding the Challenges of Finding Grey Literature.

On Wednesday, November 30, I joined the GreyLit: Intro and Search Strategies session. It was a hands-on learning session focused on finding grey literature. It was very interesting.

The conference was quite stimulating, informative and useful and I look forward to adding the new techniques to my armamentarium to seek, find…and explore more grey literature.

Alyssa Grimshaw | Drexel University

Library Services Assistant IV / MSLIS Student | Cushing/Whitney Medical Library / Drexel University

The 18th International Conference on Grey Literature was an exceptionally eye-opening experience. In regards to grey literature I consider myself a novice, but found this conference enlightening, as it clearly illustrated the benefits of promoting and utilizing grey literature within the library system.

The conference started out strong with the Keynote Address by Taryn Rucinski. Rucinski was very energetic and informative, discussing all of the literature found within the law grey literature. I was truly flabbergasted to discover that one can find expert testimony on a large wide array of different subjects in the legislative proceedings on government websites. This is just one example of the many exceptional ways to utilize grey literature.

The conference also helped me uncover a great resource – The Grey Literature Report! The New York Academy of Medicine publishes this report bi-monthly and takes all of the obscure grey literature and makes it easily searchable! I particularly enjoyed the international aspect of the conference because it allowed me to learn a little more about how other countries use and preserve grey literature. I believe this to be incredibly important because in order for libraries to grow and develop they should be able to learn from, and interconnect with, one another. Each day of the conference was filled with valuable information and great tips that I intend to bring back to my library and apply in order to help our patrons!

Joachim Schöpfel at GL18. Photo by Danielle Aloia.

Kate Nyhan, MLS

Research and education librarian for public health | Cushing/Whitney Medical Library, Yale University

Attending one day of #GL18 at #GreyLitWeek at the New York Academy of Medicine – thanks to generous professional development funding from the National Network of Libraries of Medicine – I learned a great deal about what I don’t know. Of course, when it comes to grey literature, ignorance is a common state indeed.

- Students and even a few eminent researchers I’ve spoken with aren’t quite sure what “grey literature” is.

- Information professionals don’t always know the information ecosystem of grey literature’s producers and aggregators.

- Medical librarians might not even be aware of the diverse types of grey literature that could be relevant to biomedical and public health questions – such as the governmental administrative materials that are generated by legislative, litigation, and regulatory processes. (Read “The Elephant in the Room” by excellent speaker Taryn Rucinski of Pace University Law School for more details)

- Finally, organizations that generate grey literature sometimes seem not to know the first thing about the preservation and discovery of information – even when they are desperately trying to disseminate their high-quality, free, information products.

Thanks to the excellent talks, posters, and discussions at GL18, the unknown unknowns of grey literature are starting to become known unknowns for me. I choose that phrase to acknowledge that I’m still a novice at, say, retrieving government administrative materials, or even hard-to-find theses and dissertations – but now I’m a novice with better tools!

he New York Academy of Medicine hosted the

he New York Academy of Medicine hosted the

“On October 26th, the Academy Library convened ‘Archives, Advocacy and Change: Tales from Four New York City Collections.’ I moderated a lively conversation with all-star panelists Jenna Freedman (Barnard College), Steven Fullwood (In the Life Archive), Timothy Johnson (Tamiment Library, New York University) and Rich Wandel (The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center). The discussion hit on a lot of fascinating issues, including how archivists shape the historical record with the selection and acquisition choices they make, issues of privilege, and access for communities.”

“On October 26th, the Academy Library convened ‘Archives, Advocacy and Change: Tales from Four New York City Collections.’ I moderated a lively conversation with all-star panelists Jenna Freedman (Barnard College), Steven Fullwood (In the Life Archive), Timothy Johnson (Tamiment Library, New York University) and Rich Wandel (The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center). The discussion hit on a lot of fascinating issues, including how archivists shape the historical record with the selection and acquisition choices they make, issues of privilege, and access for communities.”  “I was excited to learn in 2016 that the Library holds

“I was excited to learn in 2016 that the Library holds  “Most of my works has a lot to do with satisfaction—satisfactions from cleaning dusted books, from placing crumbled health pamphlets into clean, acid-free envelopes, from making fitted enclosures for damaged books, from putting torn pieces together, and so much more. But all of these satisfactions is ultimately coming from that I’m contributing in preservation of the library materials to be more accessible and usable for the future! One of the most memorable item I worked through in

“Most of my works has a lot to do with satisfaction—satisfactions from cleaning dusted books, from placing crumbled health pamphlets into clean, acid-free envelopes, from making fitted enclosures for damaged books, from putting torn pieces together, and so much more. But all of these satisfactions is ultimately coming from that I’m contributing in preservation of the library materials to be more accessible and usable for the future! One of the most memorable item I worked through in  “A recent highlight for me would be our first

“A recent highlight for me would be our first

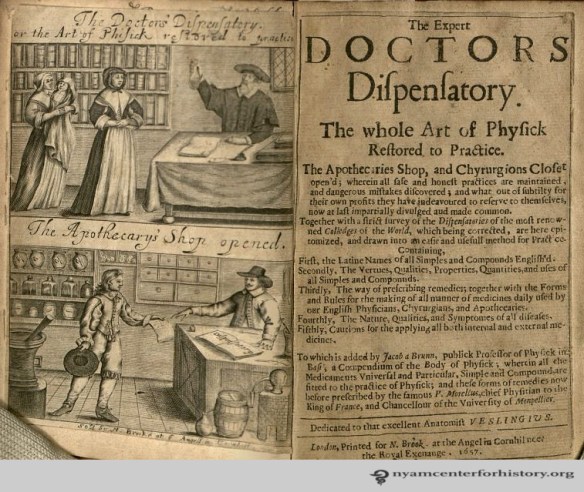

“Dr. Paul Schneiderman brought his Columbia dermatology residents to visit the rare book room on August 26th so that we could explore the history of dermatology. Looking at highlights from the dermatology collection from the 16th through the 20th centuries gave the residents a chance to think about the many ways in which their specialty has changed over time, especially since dermatology relies so heavily on visual representation. We looked at hand colored engravings, chromolithographs, photographs and stereoscopic images and the residents and their mentor engaged in lively debates about whether the descriptions and images matched with current information about some of the diseases that were shown. Not only did the residents have the opportunity to see these wonderful materials, but I had the pleasure of learning more about how to interpret the images from them.” –Arlene Shaner, Historical Collections Librarian

“Dr. Paul Schneiderman brought his Columbia dermatology residents to visit the rare book room on August 26th so that we could explore the history of dermatology. Looking at highlights from the dermatology collection from the 16th through the 20th centuries gave the residents a chance to think about the many ways in which their specialty has changed over time, especially since dermatology relies so heavily on visual representation. We looked at hand colored engravings, chromolithographs, photographs and stereoscopic images and the residents and their mentor engaged in lively debates about whether the descriptions and images matched with current information about some of the diseases that were shown. Not only did the residents have the opportunity to see these wonderful materials, but I had the pleasure of learning more about how to interpret the images from them.” –Arlene Shaner, Historical Collections Librarian What follows is an engaging, often-times laugh-out-loud narrative of Dick’s new life with diabetes. Accompanying each chapter are charming illustrations by W. Joseph Carr.

What follows is an engaging, often-times laugh-out-loud narrative of Dick’s new life with diabetes. Accompanying each chapter are charming illustrations by W. Joseph Carr. In another chapter, Dick agrees to be a diabetes research participant at a lab. In a passage that would make any 21st century Institutional Review Board member cringe, the doctor explains to Dick what it means to be a “guinea-pig”:

In another chapter, Dick agrees to be a diabetes research participant at a lab. In a passage that would make any 21st century Institutional Review Board member cringe, the doctor explains to Dick what it means to be a “guinea-pig”: Another highlight of the book is Dick’s (somewhat inexplicable) trip to Munich, Germany with his mother during Adolf Hitler’s reign. During the trip, Dick is hospitalized with painful sores. The situation is, understandably, quiet stressful for Dick, but he takes it in stride:

Another highlight of the book is Dick’s (somewhat inexplicable) trip to Munich, Germany with his mother during Adolf Hitler’s reign. During the trip, Dick is hospitalized with painful sores. The situation is, understandably, quiet stressful for Dick, but he takes it in stride: