Today’s guest post is written by Lisa Rosner, Ph.D., Distinguished Professor of History at Stockton University. Recent publications include The Anatomy Murders (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009) and Vaccination and Its Critics (ABC-Clio, 2017). She is the project director and game developer for The Pox Hunter, funded by an NEH Digital Projects for the Public grant. On Thursday, April 6, Lisa will give her talk, “Lady Mary’s Legacy: Vaccine Advocacy from The Turkish Embassy Letters to Video Games.” To read more about this lecture and to register, go HERE.

In a letter dated April 1, 1717 – 300 years ago — Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689–1762), the wife of the British ambassador to Turkey, provided the first report from an elite European patient’s perspective of the middle-eastern practice of inoculation, or ingrafting, to prevent smallpox. She wrote to her dear friend, Sarah Chiswell:

“I am going to tell you a thing that will make you wish yourself here. The small-pox, so fatal, and so general amongst us, is here entirely harmless, by the invention of engrafting, which is the term they give it. There is a set of old women, who make it their business to perform the operation, every autumn, in the month of September, when the great heat is abated. People send to one another to know if any of their family has a mind to have the small-pox; they make parties for this purpose, and when they are met (commonly fifteen or sixteen together) the old woman comes with a nut-shell full of the matter of the best sort of small-pox, and asks what vein you please to have opened. She immediately rips open that you offer to her, with a large needle (which gives you no more pain than a common scratch) and puts into the vein as much matter as can lie upon the head of her needle, and after that, binds up the little wound with a hollow bit of shell, and in this manner opens four or five veins…

The children or young patients play together all the rest of the day, and are in perfect health to the eighth. Then the fever begins to seize them, and they keep their beds two days, very seldom three. They have very rarely above twenty or thirty in their faces, which never mark, and in eight days time they are as well as before their illness. Where they are wounded, there remains running sores during the distemper, which I don’t doubt is a great relief to it. Every year, thousands undergo this operation, and the French Ambassador says pleasantly, that they take the small-pox here by way of diversion, as they take the waters in other countries. There is no example of any one that has died in it, and you may believe I am well satisfied of the safety of this experiment, since I intend to try it on my dear little son.”

Mary Wortley Montagu with her son Edward, by Jean-Baptiste van Mour. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

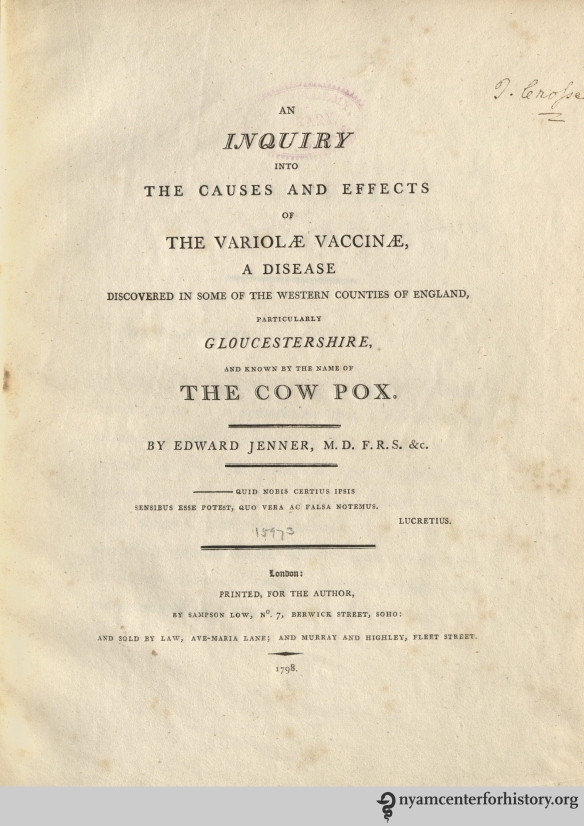

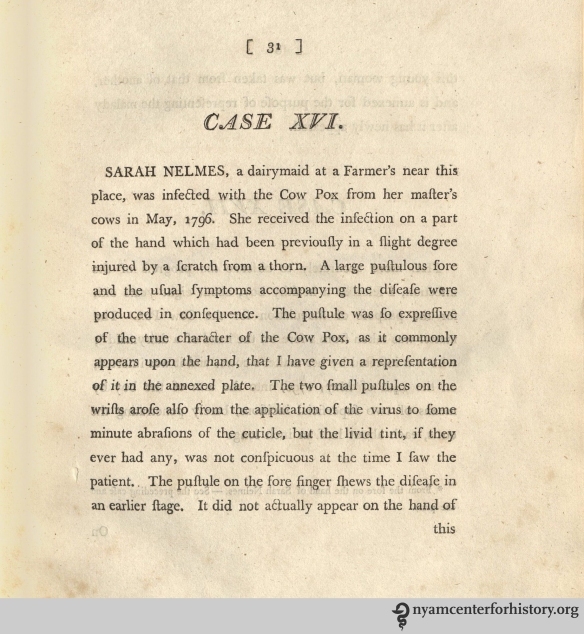

This is probably the most famous passage in all Lady Mary’s voluminous correspondence. It deserves even more attention than it usually gets, because it is the first example, in the western history of medicine, of a mother’s perspective on the practice of immunization. We tend to hear a great deal from scientists like Jenner about their discoveries, but much less from mothers who adopted their techniques for children.

But Lady Mary was not just a mother, she was also an acute observer with an inventive and inquisitive mind, and a particular interest in what we would now call public health practices. She had lost a beloved brother to smallpox; she had also contracted the disease, and though she survived, she carried the scars for the rest of her life. As she traveled from London to Constantinople, she was particularly interested in innovations and cultural attitudes toward hygiene and domestic health, especially as they affected women’s lives.

Her enthusiasm for light, clean, airy environments comes through in her very first letter, written from the Netherlands. She wrote:

“All the streets are paved with broad stones and before many of the meanest artificers doors are placed seats of various coloured marbles, so neatly kept, that, I assure you, I walked almost all over the town yesterday, incognito, in my slippers without receiving one spot of dirt; and you may see the Dutch maids washing the pavement of the street, with more application than ours do our bed-chambers.”

For that reason, she noted:

“Nothing can be more agreeable than travelling in Holland. The whole country appears a large garden; the roads are well paved, shaded on each side with rows of trees.”

She was much less pleased with Vienna, for though there were certainly many magnificent sights, the city itself was dark and crowded. She complained:

“As the town is too little for the number of the people that desire to live in it, the builders seem to have projected to repair that misfortune, by clapping one town on the top of another, most of the houses being of five, and some of them six stories … The streets being so narrow, the rooms are extremely dark; and, what is an inconveniency much more intolerable … there is no house has so few as five or six families in it.”

As her travels continued throughout the fall and winter, another custom, neglected in England, caught her attention: the stove, valuable for warmth and for lengthening the growing season. At one of the formal dinners she attended, she was offered oranges and bananas and wondered how they could possibly be grown in Austria. She wrote:

“Upon inquiry I learnt that they have brought their stoves to such perfection, they lengthen their summer as long as they please, giving to every plant the degree of heat it would receive from the sun in its native soil. The effect is very near the same; I am surprised we do not practise [sic] in England so useful an invention. This reflection leads me to consider our obstinacy in shaking with cold, five months in the year rather than make use of stoves, which are certainly one of the greatest conveniencies [sic] of life.”

Mary Wortley Montagu in Turkish dress. Souce: Wikimedia Commons.

When she arrived in Constantinople and spent time with ladies of the court, both Turkish and European, Lady Mary continued to pursue her interest in gardens, in baths, in the light airy spaces found in both European and Turkish households. She was not the first European to report on the practice of “ingrafting”: her family physician in Constantinople, Dr. Emmanuel Timoni, had previously sent a report to the Royal Society of London. But seeing a disease, so dangerous in Europe, treated as an excuse for a children’s party turned her into an advocate. As she wrote:

“I am patriot enough to take the pains to bring this useful invention into fashion in England, and I should not fail to write to some of our doctors very particularly about it, if I knew any one of them that I thought had virtue enough to destroy such a considerable branch of their revenue, for the good of mankind. But that distemper is too beneficial to them, not to expose to all their resentment, the hardy wight that should undertake to put an end to it. Perhaps if I live to return, I may, however, have courage to war with them. Upon this occasion, admire the heroism in the heart of your friend.”

After she returned to London, she kept her promise “to war” with the physicians in support of inoculation. When smallpox broke out in her social circle in 1722, she decided to inoculate her daughter, and the operation was performed with great success. Physicians who visited her found “Miss Wortley playing about the Room, cheerful and well,” with a few slight marks of smallpox. Those soon healed, and the child recovered completely. The visiting physicians were impressed, and they began to incorporate inoculation into their own practices.

As the epidemic raged, Lady Mary convinced her most prominent friend, Caroline, Princess of Wales, to inoculate the two royal princesses, Amelia and Caroline. Having received the royal seal of approval, smallpox inoculation became fashionable practice among British elites throughout the 18th century.

Memorial to the Rt. Hon. Lady Mary Wortley Montague erected in Lichfield Cathedral by Henrietta Inge. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In 1789, Mrs. Henrietta Inge, Lady Mary’s niece, erected a memorial to her accomplishments in Litchfield Cathedral. The text reads:

“[She] happily introduc’d from Turkey, into this country the Salutary Art Of inoculating the Small-Pox. Convinc’d of its Efficacy She first tried it with Success on her own Children, And then recommended the practice of it To her fell-w-Citizens. Thus by her Example and Advice, We have soften’d the Virulence, And excap’d the danger of this malignant Disease.”

We can recognize in Lady Mary – and in Mrs. Inge — advocates of a kind met with very frequently in the history of vaccination: mothers whose personal experience led them to champion the discoveries that preserved their family’s health and well-being.

Bibliography:

- Grundy, Isobel. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Montagu, Lady Mary Wortley. Letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. Written during her travels in Europe, Asia, and Africa. Paris: Firman Didot, 1822. Available in many editions online.

- Rosner, Lisa. Vaccination and Its Critics. A Documentary and Reference Guide. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2017.