By Paul Theerman, Associate Director, Center for the History of Medicine and Public Health

In the middle of the 19th century, the greatest surgical innovation was anesthesia. In the time that the television show The Knick is set, around 1900, the greatest surgical innovation was aseptic, or sterile, surgery. Anesthesia allowed for longer and steadier operations; aseptic surgery allowed for more successful ones. It changed surgical techniques, training, procedures, and equipment alike.

Sterile dressings. From Charles Truax’s The Mechanics of Surgery, ed. James M. Edmonson (1899; reprint ed., San Francisco: Norman Publishing, 1988). Click to enlarge.

The Knick shows first the techniques not of aseptic surgery, but of antiseptic surgery—that is, surgery under conditions designed to combat germs. Spraying the operating room with carbolic acid, and dipping beards in the same chemical, were two such techniques. Aseptic surgery went farther, creating surgical conditions without germs. Thus aseptic surgery led to sterilizing instruments; swabbing down patients; robing, masking, and gloving surgeons; and dressing wounds with sterile dressings. Such procedures began in the 1880s, and by the early 1900s were becoming more and more standard.

Our colleague Jim Edmonson of the Dittrick Museum of Medical History in Cleveland, Ohio, has explored the effect of aseptic surgery on medical instruments and instrument making. Aseptic surgery led to the sale and use of instrument sterilizers, of sterile gauze and cotton, and most especially of instruments designed to be readily and effectively sterilized, as well as inexpensively made. Thus metal soon replaced the wooden and ivory handles of surgical instruments. Jim quotes a Chicago surgeon, Nicholas Senn, in 1902:

All attempts at ornamentation have been abandoned . . . . The modern surgical instruments are made as plain and smooth as possible. Knives and retractors are made of one piece of steel, all niches and crevices being avoided wherever possible. Scissors and forceps are made so that the two parts may be readily separated and joined again.1

Scalpels. From Charles Truax’s The Mechanics of Surgery, ed. James M. Edmonson (1899; reprint ed., San Francisco: Norman Publishing, 1988). Click to enlarge.

To take care of scissors and forceps, German instrument makers developed the “Aseptic Pin Lock,” patented in the United States by Paul Henger of Stuttgart in 1892.2 This design allowed the device to be easily disassembled, sterilized, and then reassembled. Since the pieces could also be mass-produced rather than handcrafted, these instruments swept through the market, dominating from the 1890s to the 1930s. The idea of aseptic surgery pushed innovation throughout the whole of the surgical enterprise.

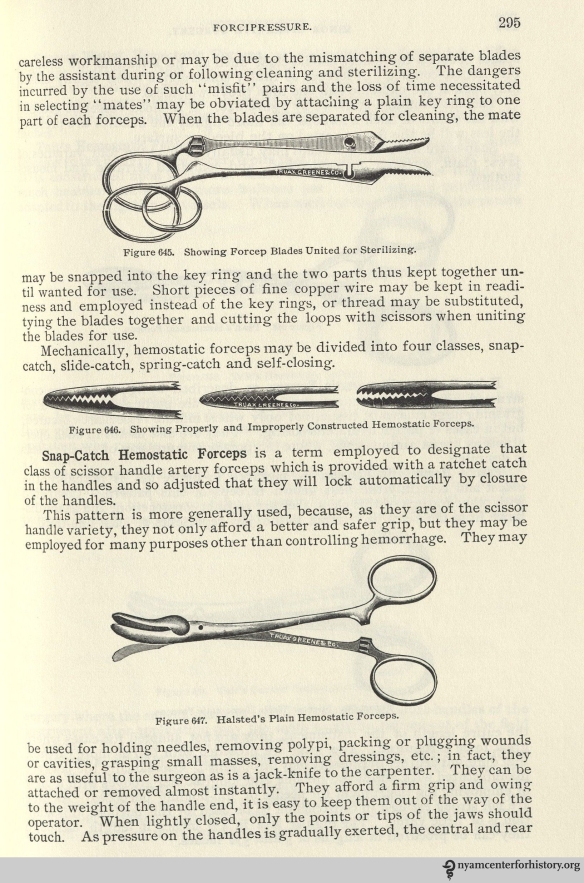

We show here images of the equipment of aseptic surgery, taken from Charles Truax’s The Mechanics of Surgery, ed. James M. Edmonson (1899; reprint ed., San Francisco: Norman Publishing, 1988). One of the images is of “Halsted’s Plain Hemostatic Forceps,” developed by William Halsted, the surgeon on whom The Knick’s Dr. Thackery is based, and designed to clamp blood vessels to control the loss of blood during surgery.

Thermal sterilization. From Charles Truax’s The Mechanics of Surgery, ed. James M. Edmonson (1899; reprint ed., San Francisco: Norman Publishing, 1988). Click to enlarge.

Sterilizers. From Charles Truax’s The Mechanics of Surgery, ed. James M. Edmonson (1899; reprint ed., San Francisco: Norman Publishing, 1988). Click to enlarge.

Forceps. From Charles Truax’s The Mechanics of Surgery, ed. James M. Edmonson (1899; reprint ed., San Francisco: Norman Publishing, 1988). Click to enlarge.

Sterilized gauze. From Charles Truax’s The Mechanics of Surgery, ed. James M. Edmonson (1899; reprint ed., San Francisco: Norman Publishing, 1988). Click to enlarge.

References

1. James M. Edmonson, American Surgical Instruments: The History of Their Manufacture and a Directory of Instrument Makers to 1900 (San Francisco: Norman Publishing, 1997), p. 14, quoting Nicholas Senn, Practical Surgery for the General Practitioner.

2. Idib, p. 137, and figure 170. U.S. Patent 474,130, issued May 3, 1892. You can also see this at the U.S. Patent and Trademark site: http://www.uspto.gov/patents/process/search/

Pingback: Cómo la esterilización cambió la cirugía

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Vol. #13 | Whewell's Ghost

Hi Paul, et al,

I’m flattered by the notice of my research on instruments and asepsis — still a subject of interest after all these years! We’re having fun with The Knick, too, finding a few gaffes and anachronisms that invariably creep into historical productions. See blog postings by Catherine Osborn:

http://dittrickmuseumblog.com/2014/09/26/listening-to-the-body-stethoscopes-in-1900/

http://dittrickmuseumblog.com/2014/09/12/blood-rises-tension-and-truth-in-the-knick/

Pingback: Ga. woman wins $40K in State Farm bad-faith auto body ‘prevailing prices’ dispute | Repairer Driven News