By Anne Garner, Curator, Center for the History of Medicine and Public Health

One hundred years ago today, Congress approved the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act. The Act’s passage critically impacted drug policy for the remainder of the century, and the habits of physicians with regard to prescribing and dispensing medicine.

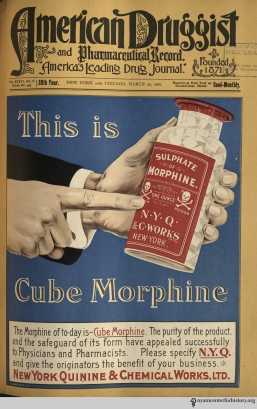

By 1900, use of narcotics was at its peak for both medical and non-medical purposes. Advertisements promoting opium- and cocaine-laden drugs saturated the newspapers; morphine seemed more easily obtainable than alcohol; and widespread sale of drugs and drug paraphernalia gained the attention of medical professionals and private citizens alike.1 State regulations failed to effectively curb distribution and use.2

Physicians and pharmacists recognized they had an image problem. In 1901, the American Pharmaceutical Association formed a committee to study the country’s drug problem and recommended the ban of non-medical drug use.3 The American Medical Association seconded the APA’s pitch and strongly advocated for federal legislation.4

This groundswell in support of federal action among local medical professionals also had roots overseas. In the aftermath of the Spanish-American war, the U.S. inherited control of the Philippines, and with it a serious opium problem. An American missionary, Charles Henry Brent, convened a commission in 1903 that recommended narcotics be subject to international control.5 Roosevelt seized on these findings, recognizing an opportunity to improve relations with China. In 1908 he initiated an international conference in Shanghai to talk about the narcotics problem. The President sent Brent and Hamilton Wright, U.S. Opium Commissioner, to represent the U.S.6 Wright, an outspoken, charismatic, and controversial figure, was central to the eventual passage of the Harrison Act.

Passage of a federal law would not be easy. In April of 1910, at Wright’s behest, Representative David Foster proposed a bill banning the non-medical use of opiates, cocaine, chloral hydrate, and cannabis, with harsh penalties for violations. The purchase of patent medicines containing any of these ingredients would require tax stamps and strict record-keeping. Proponents of the bill stressed the link between criminalization and drug use. Despite Wright’s best efforts, the uncompromising Foster bill garnered strong resistance from manufacturers and druggists, and died in Congress.7

A clipping from the library’s Healy Collection, which contains 19th century images, mostly clipped from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated News and Harper’s Weekly. Click to enlarge.

Two more international conferences followed, at The Hague in 1911 and 1912. Soon after, Wright renewed his commitment to pass federal anti-drug legislation. A new bill proposed by Tammany representative Francis Burton Harrison, again at Wright’s urging, looked very similar to the Foster bill. But after two years of negotiations in Congress, the final legislation incorporated several key compromises. Physicians could dispense medication to patients without record-keeping. Patent medicines with legal amounts of narcotic substances could be sold by mail order or in general stores. Cannabis and chloral hydrate were omitted from regulation. With these concessions, opposition from pharmaceutical and medical professionals softened, agreement was reached, and the bill was signed into law on December 17, 1914.8

The immediate impact of the Act’s passage was confusion. The law offered only vague implementation guidelines. Was it largely a taxation measure, or was it intended to monitor and regulate professional activity? The Act’s major ambiguity related to the authority of physicians to prescribe maintenance doses of narcotics to already-addicted patients. Two 1919 Supreme Court cases clarified the issue. U.S. vs. Doremus found the Harrison Act constitutional and validated the government’s ability to regulate prescription practices for addicts. Webb et al. vs. U.S. denied physicians the power to provide maintenance doses.

The Supreme Court decisions forced addicts to locate new sources. They turned to the black market, where they paid top dollar. Petty crime increased.9 Penalties for violation of the Harrison Act were harsh. In the early years of the law, conviction numbers were relatively low—most years fewer than 500—but by 1919, the year of the Supreme Court rulings, convictions showed a marked upward trend. By 1923, convictions were approaching 5,000 per annum.10

The effect of the legislation on addicts was not viewed unsympathetically by the medical establishment, or even by law enforcement. Even the head of New York’s dope squad, Lieutenant Scherb, seemed concerned: “Many of [the addicts] are doubled up in pain at this very minute and others are running to the police and hospitals to get relief….the suffering among them is really terrible.”11 Beginning in 1919, authorities and public health officials cooperated to develop 44 addiction recovery facilities. These new facilities were short-lived, and most had closed by 1921. Unpopular with the public, many shut down because the lion’s share of patients found themselves back on the streets again.

NYAM holds a scrapbook of newspaper clippings from 1926-1927 illustrating that drug abuse was still front and center in America’s mind well after the Harrison Act’s passage.12 Most articles framed narcotic users as criminals: what was once a legal pastime was now seen as a major threat to American society. One clipping quotes Harvey Waite of the Association for the Prevention of Drug and Narcotic Addicts of Michigan: “Drug addicts are a menace to the peaceful citizens of the United States because from them come the most notorious criminals and lawbreakers.”

The Harrison Act’s most lasting impact was in how it shifted the public conversation from a discussion about regulating a legal activity to eliminating an illegal one. The Act would form the cornerstone of all drug legislation to come, including the Controlled Substance Act of 1970.

References

1. Musto, David F. The American Disease Origins of Narcotic Control. New York: Oxford, 1999. Pp. 3-8.

2. Morgan, H. Wayne. Drugs in America. A Social History 1800-1980. Pp. 101-102.

3. Morgan, p. 102.

4. Musto, p. 56-57.

5. Courtwright, David T. Dark Paradise Opiate Addiction in America before 1940. Cambridge: Harvard, 1982.

6. Morgan, 99-100.

7. Musto, 47-48.

8. Morgan, 106-108 and Musto, 59-61.

9. Hodgson, Barbara. In the Arms of Morpheus. The Tragic History of Laudanum, Morphine, and Patent Medicines. Buffalo: Firefly, 2001. P. 128.

10. Erlin and Spillane, pp. 44-45.

11. The New York Times, April 15, 1915.

12. [Narcotics]. Clippings from newspapers from Dec. 1926-Sept. 1932. [New York?, 1926-1932]. 3 v. Email history@nyam.org to request.

Pingback: Whewell's Ghost

Super interested in that brilliant color advertisement up top. We have that issue at the Internet Archive but it doesn’t have that “cube morphine” ad in it. Any more information on it?

https://archive.org/stream/americandruggis02unkngoog#page/n164/mode/2up

Hi, Jessamyn. On Internet Archive, I can find issue numbers 5 and 7 of volume 36, but not issue 6.

Dang, I was sure I was looking at the right volume. A curious omission for us. Thanks for the second set of eyes.

Pingback: US CBD Laws by State, Including Marijuana Laws - Cannabis History

Pingback: United States CBD and Marijuana Laws - Bhangers

Pingback: Is CBD Legal in the United States? – CBD & Marijuana State Laws – CBD News Link

Pingback: Is CBD Legal in the United States? – CBD & Marijuana State Laws | %site_title%

Pingback: Timeline: Purdue Pharma Took Notes From Early 1900s Patent Medication Marketing Tactics – The Opioid Effect

Pingback: 55 Weird History Facts