By Rebecca Dixon, Public Engagement Intern

This Summer, the NYAM Library hosted our first-ever Public Engagement Intern. Rebecca is about to enter her second year as a Library Science student at Pratt. As part of her internship, she was asked to produce a blog post on a topic of her own choosing. If you are a library science graduate student interested in an internship at our library, be sure to look out for calls on our social media channels.

As the New York Academy of Medicine’s Library Public Engagement Intern, I’ve had the incredible opportunity and privilege to work with the library’s collection. Inspiration can strike anywhere in the library’s vast holdings, but it struck me when I stumbled across some wheat-free recipe pamphlets among the cookery items in the collection, one of many subject strengths of the NYAM Library. The number of wheat-free pamphlets and recipes in the collection, all dating from 1917 and 1918, piqued my interest. I was intrigued and eager to learn more about why so many of these pamphlets might be in the collection, as they reminded me of current day online recipe blogs. Were people in 1918 cutting wheat because of dietary restrictions or to follow the latest fad diet? Digging deeper into the collection would reveal the answer.

While I didn’t find any recipe books on the South Beach, Paleo, or Keto diets in the collection, I found plenty of recipe pamphlets urging citizens to conserve wheat, sugar, meat, fats, and milk (Wilson et al., 1917). I found pamphlets and posters encouraging Americans to conserve wheat to increase exports to Allied countries, and British ones encouraging their citizens to cut out wheat due to the decreased production. These pamphlets and recipe books were clearly of great historical importance, but is there a reason why the library collected so many specific pamphlets on rationing wheat? For answers I turned to the collection where I found all these pamphlets: the Margaret Barclay Wilson Collection of Books on Foods and Cookery.

Margaret Barclay Wilson: Fellow of the New York Academy of Medicine, Professor of Home Economics and Head of the Physiology and Hygiene Department at Hunter College, Honorary Librarian at Hunter College, Doctor of Medicine, friend of Andrew Carnegie, and pioneer and expert in food economy, there is no shortage of accolades for the remarkable Dr. Wilson (Tanzer, H. 1948). In 1929 Dr. Wilson generously donated her collection of over 4,000 works of cookery and nutrition to the NYAM Library. Her collection contains many items dealing with food rationing because she was commissioned by the British government to prepare a report on how to deal with food shortages caused by World War I. The government was interested in any and all ways to combat these shortages. For wheat shortages that included, finding alternatives to wheat, encouraging people to reduce and ration the use of wheat, and regulating the production and use of wheat. Dr. Wilson prepared a report on the use of flour in the making of bread, which was used to mitigate the ongoing wheat shortage change the laws regarding the use of flour in making bread. As she also served as a member of the advisory council of the New York City Health Department from 1915 to 1917, where she prepared papers on food economy for circulation by the department, her collection on food rationing includes items from both the US and abroad (Tanzer, H. 1948).

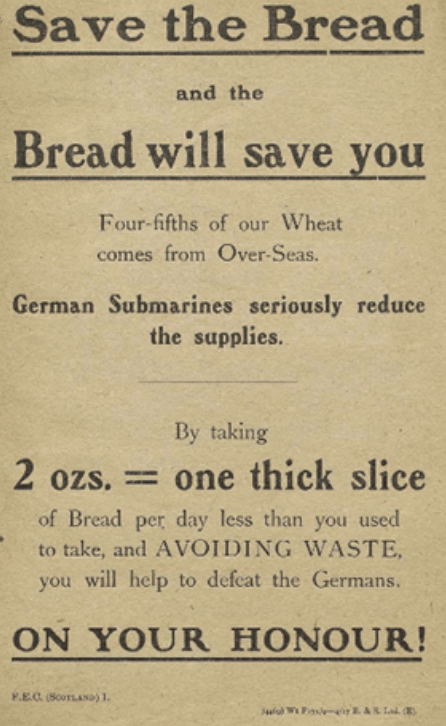

The governments of the allied forces and various other organizations detailed the best methods for rationing wheat and other target food groups. Rationing was encouraged through various means: having one wheatless meal a day, eating less cake, pastries, and pie, using bread scraps in cooking, replacing bread with other carbohydrates such as potatoes, and fully or partially replacing wheat in recipes (Haskin, 1917) (National Wholesale Grocers’ Association of the United States, 1917). Through a series of pamphlets, cookbooks, and posters, citizens and patriots were encouraged to save two ounces of bread per person per day lest rationing become mandatory (F.E.C. (Scotland), 1917) (J., 1917). Many of these books and pamphlets appealed directly to women as they controlled 90% of the food consumption of America. One recipe book even begins with a letter from Herbert Hoover, head of the US Food Administration for the war effort and future US president, appealing directly to American women to pledge themselves to the food conservation cause (Haskin, 1917).

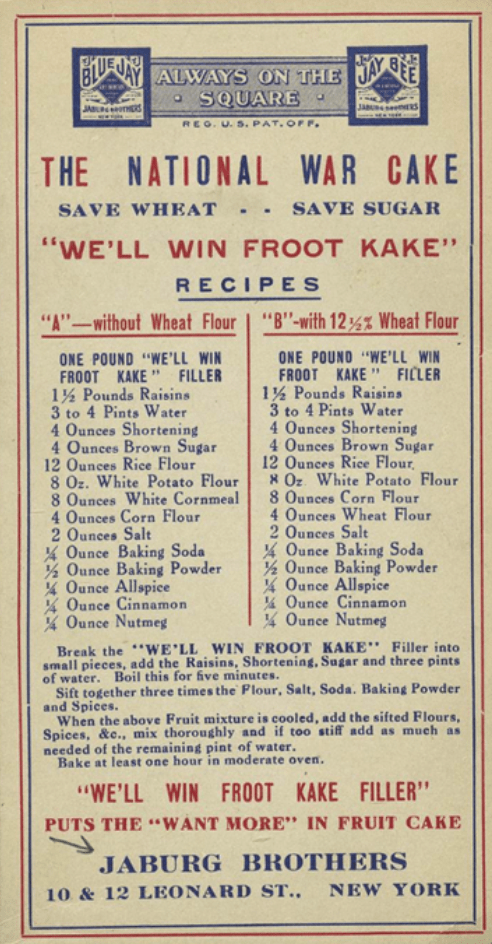

The war had already caused a global food shortage, and America’s allies, including the United Kingdom and France, were relying more than ever on imports of wheat (F.E.C. (Scotland), 1917). America was one of the exporters, expected to make up almost half of the necessary supply (Chaddock, 1917). But between the dwindling surplus from the good harvest years of 1914 (the first year of the war, of which 37% of the yield was exported) and 1915, and a barely sufficient harvest in 1916, the projected harvest for 1917 would not be enough (Chaddock, 1917). The wheat was not safe as it was shipped across the Atlantic since shipments were susceptible to attack by German U Boats (F.E.C. (Scotland), 1917). If the US government could convince people to conserve one pound of wheat flour per week, 133,000,000 bushels of wheat would be saved (National Wholesale Grocers’ Association of the United States, 1917). The New York State Food Commission, Bureau of Conservation even decreed that for every pound of wheat flour the seller also had to sell a pound of authorized wheat flour substitute (New York (State) & United States Food Administration, 19). The main strategy to conserve wheat, however, was to publish tested recipes that cut out or cut back on wheat with flour alternatives recommended by the US Food Administration (Royal Baking Powder Company, 1918). Baking at home was proclaimed a national duty (Chance et al., 1917).

My research inspired me to try my hand at one of these war time recipes. I had no shortage to choose from. These recipes advised the reader to forgo white flour completely and fully or partially substitute whole wheat flour and bread flour with many other flours and ingredients. These replacements included corn meal, oat flour, barley flour, oatmeal, graham flour, rye flour, boiled and mashed potatoes (sweet or white), buckwheat flour, hominy, cooked rice, breadcrumbs, tapioca, and maize flour. While I was tempted by some intriguing sounding recipes like “Spider Corn Bread” (Derouet, 1917), “Eggless, Milkless, Butterless Cake” (Royal Baking Powder Company, 1918), “Cornmeal and Prune Fluff” (New York City Food Aid Committee, 1917), “Date and Hominy Gems” (Neil, 1917), “Virginia Spoon Bread” (Chaddock, 1917) or “Invalid Pudding” (Chance et al., 1917), I ultimately decided to go with a more familiar recipe to ensure I could easily source the ingredients and didn’t need to procure any additional kitchen equipment.

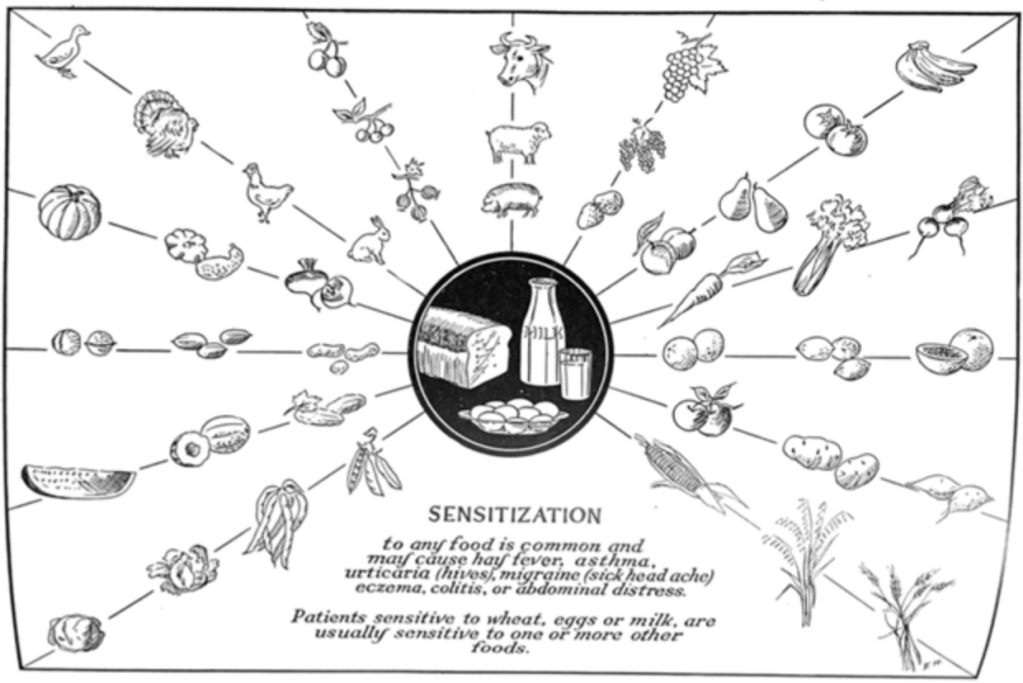

As I am not only “rationing wheat to support the war effort” but must stick to a gluten-free diet for health reasons, I had to find a recipe that was not only wheat-free, but also gluten-free (without wheat, barley, or rye). Many of the recipes only reduced wheat, instead cutting it out completely, or substituted rye or barley flour, and so were not truly wheat- or gluten-free. Luckily there are many recipes available in the collection, so I still had plenty of options that were both wheat-free and gluten-free. One pamphlet, published by the Royal Baking Powder Company, had several suitable recipes to choose from. The pamphlet, titled “Wheatless Recipes,” was published in New York. On the cover it quotes the US Food Administration and calls to “let all who can go without wheat.” All the recipes on the page above fit the criteria, but I’m going to stick to the classic Chocolate Cake because its wheat substitution is unique. This recipe substitutes a mix of oat/rice/barley flour and mashed potatoes for wheat flour.

I was extremely pleased with how the cake came out; it is a bit dense, almost like a pound cake, which I guess is to be expected due to the inclusion on mashed potatoes. Even 4 teaspoons of baking powder were not enough to make this recipe light and fluffy. Also, since the recipe calls for only one cup of brown sugar, it is not super sweet. If you prefer your desserts on the less-sweet side, this is perfect for you, but if you have more of a sweet tooth, like me, you can serve it with frosting or ice cream.

I had fun asking my family and friends to try the cake and ask if they could identify what was different about the cake. Many mentioned it wasn’t very sweet and that it was dense, but no one could guess I used oat flour and mashed potatoes instead of wheat flour. If you try this or any of the other recipes, let us know how they turn out!

References

Chaddock, R. E. (1917). Wheat substitutes. Diversion of intelligence and publicity.

Derouet, L. C. (1917). Wheatless recipes. no publisher specified.

J., V. (1917). Wheatless Days. A way to meet them. Sixty recipes for war time, etc. [By V.J.]. Truslove & Hanson.

The Associate Alumnae of Hunter College, Lewinson, R., Hahn, E. A. (Ed.). (1946, January). Margaret Barclay Wilson A.B., M. Sc., M. D., Sc. D. The Alumnae News.

Royal Baking Powder Company (Ed.). (1917). Wheatless recipes. Royal Baking Powder Company.

Save the wheat and help the fleet: Eat less bread. (1914). [Graphic]. Hazell, Watson & Viney.