By Paul Theerman, Arlene Shaner, Bert Hansen, and Melissa Grafe

On Tuesday, October 18, three esteemed librarians and historians will gather—virtually—to discuss the history and prospect of medical libraries. The event features the Library’s own Historical Collections Librarian, Arlene Shaner, speaking on the development of our collections; historian of medicine Dr. Bert Hansen, on how libraries helped shape the development of medicine through history; and Dr. Melissa Grafe, head of the Medical Historical Library at Yale School of Medicine, on the future of historical collections such as the Academy Library’s. If you are interested in attending, please register here. To learn about what these speakers will present, keep reading!

Arlene Shaner, “‘A Rich Storehouse’: The NYAM Library’s Extraordinary Collections”

Arlene Shaner, our first panelist, will talk about the evolution of the NYAM Library and its collections, starting with Isaac Wood’s gift of his set of Martyn Paine’s Commentaries to the brand-new organization on January 13, 1847. What he and the early Academy Fellows had in mind was a working collection of books and journals that they would create for their own use. Because the Academy had no home of its own, and very little money, the collections grew at a very modest pace for the first few decades.

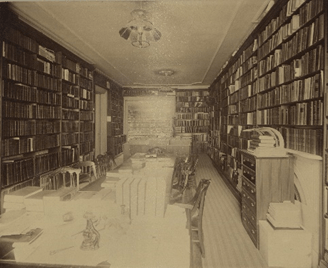

The purchase of a building in 1875 provided space for the collections to grow. The generosity of Dr. Samuel Smith Purple, who donated over 2000 journal volumes of his own after the Academy moved into its West 31st Street brownstone (at left), coupled with the 1878 decision of the Fellows to open the Library to all who wished to use it, dramatically changed the Library’s trajectory.

It opened the door to what Librarian Janet Doe later referred to as “a snowball of gifts which has rolled down through the years, gathering momentum and throwing off new snowballs that roll into other libraries.”

Shaner will offer a brief overview of some of the major gifts that helped the library become one of the most important history of medicine collections in the country, if not the world, and also tell the much less well known story of how the Library contributed to the growth of many other collections. She will also look briefly at how changes in the way information is disseminated have transformed, and continue to transform, the NYAM Library.

Bert Hansen, “The Academy Library’s Contributions to American Medicine.”

Our second panelist, historian Bert Hansen, notes that his earliest memories picture libraries as storehouses of precious treasure, an image reinforced by an architecture that made them look like giant-sized strongboxes or jewelry boxes. Built of large stone blocks and fortified like a castle, libraries he fondly recalls include the main public libraries in Chicago, Newark, and New York City, plus Butler Library at Columbia and the Morgan Library from his college years (as seen below, with NYAM the sixth). The decorated, jewelry-box style often continues inside with marbled lobbies and wood-paneled reading rooms.

But for this presentation, Hansen has gone in a new direction, focusing his attention on the kinds of contribution that libraries like that of NYAM have made to education and the world of learning in serving people who would never enter the building to examine the treasured volumes. In the recent past, virtual use through digitization has become common and will surely expand in the future. But his look at the prior century and a half will highlight other, sometimes-forgotten modes of service as examples of NYAM’s—and other research libraries’—many contributions to American medicine.

Melissa Grafe, “Preservation, Access, and the Future”

Our final panelist, librarian and historian Melissa Grafe, glimpses into the future of medical libraries and the role of physical collections in an increasingly online world. Grafe looks at the ways that technology has become deeply integrated in both medicine and in the libraries that support the medical community. Grafe will connect these modern currents to the rich trove of materials that NYAM assembled over 175 years, and the larger history that has made NYAM’s library one of the major collections connecting medical history to the present.

References

[1]Nancy Spiegel, the University of Chicago Library’s bibliographer for art and cinema, writes:

In the late 18th century, a new vision of the library arose within the context of expanding literacy, and the increased publication of books and journals for the general reading public. Enlightenment architect Étienne-Louis Boullée (1728–1799) envisioned a grand design in his proposal for a French National Library in 1785. In Boullée’s presentation, the state would take responsibility for the collection, ordering, and dissemination of all available information to its citizens.

The design for the main reading room featured a vast, barrel-vaulted ceiling and a modern shelving arrangement: stacked galleries of books over flat wall-cases. These seemingly endless bookcases were open and easily browsable, in dramatic contrast to the earlier medieval system of chaining that bound both books, and readers, to a specific location. Visitors are free to wander about and converse in small groups, but there is no provision of study desks or chairs for extensive research in this idealized environment.

Nancy Spiegel, “The Enlightenment and grand library design,” The University of Chicago Library News, April 26, 2011: https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/about/news/the-enlightenment-and-grand-library-design/, accessed October 7, 2022. The image is from Étienne-Louis Boullée, Mémoire sur les moyens de procurer à la bibliothèque du Roi les avantages que ce monument exige, 1785.