by Anthony Murisco, Public Engagement Librarian

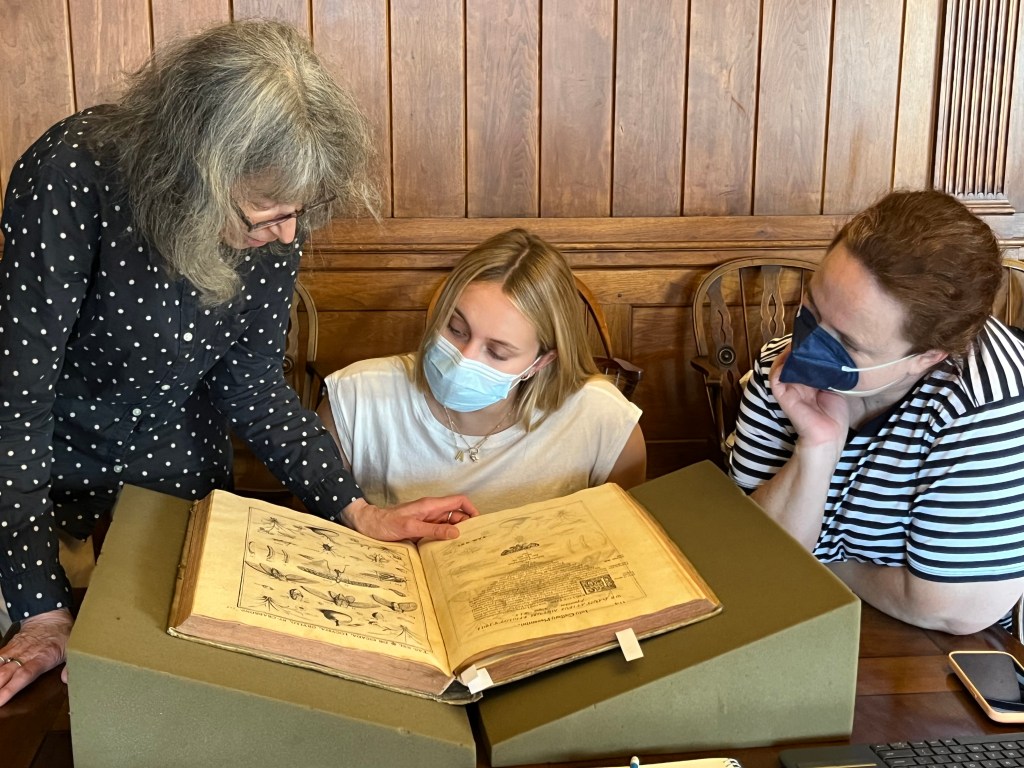

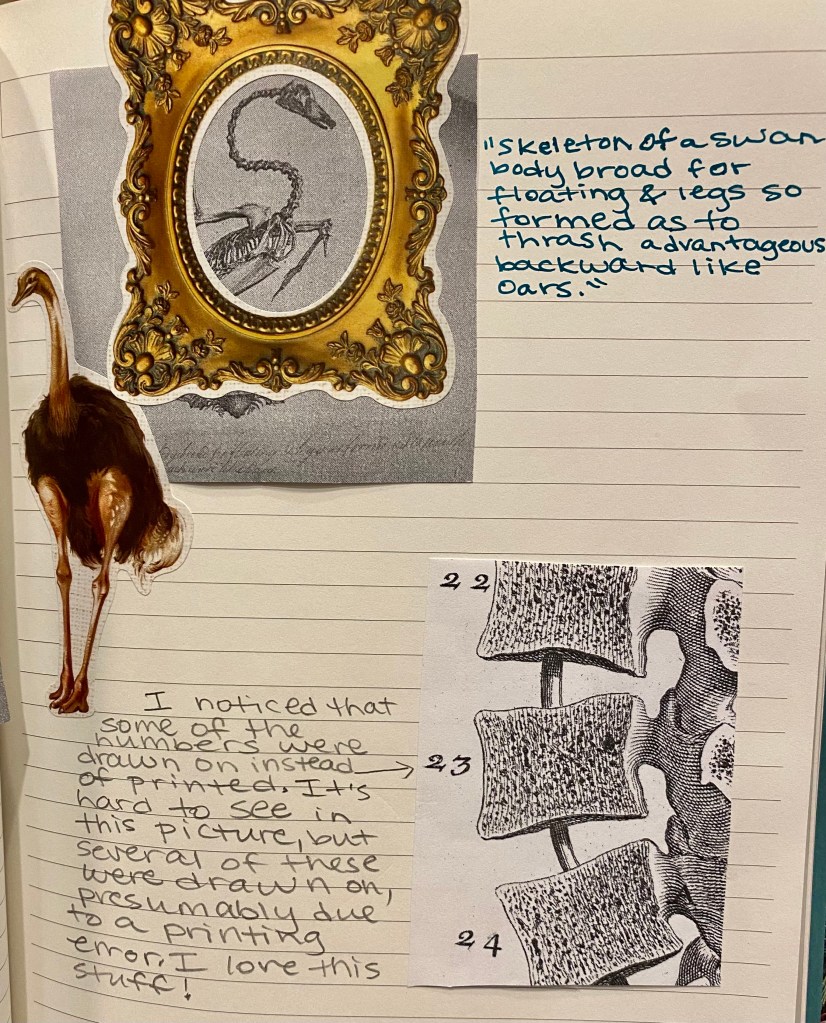

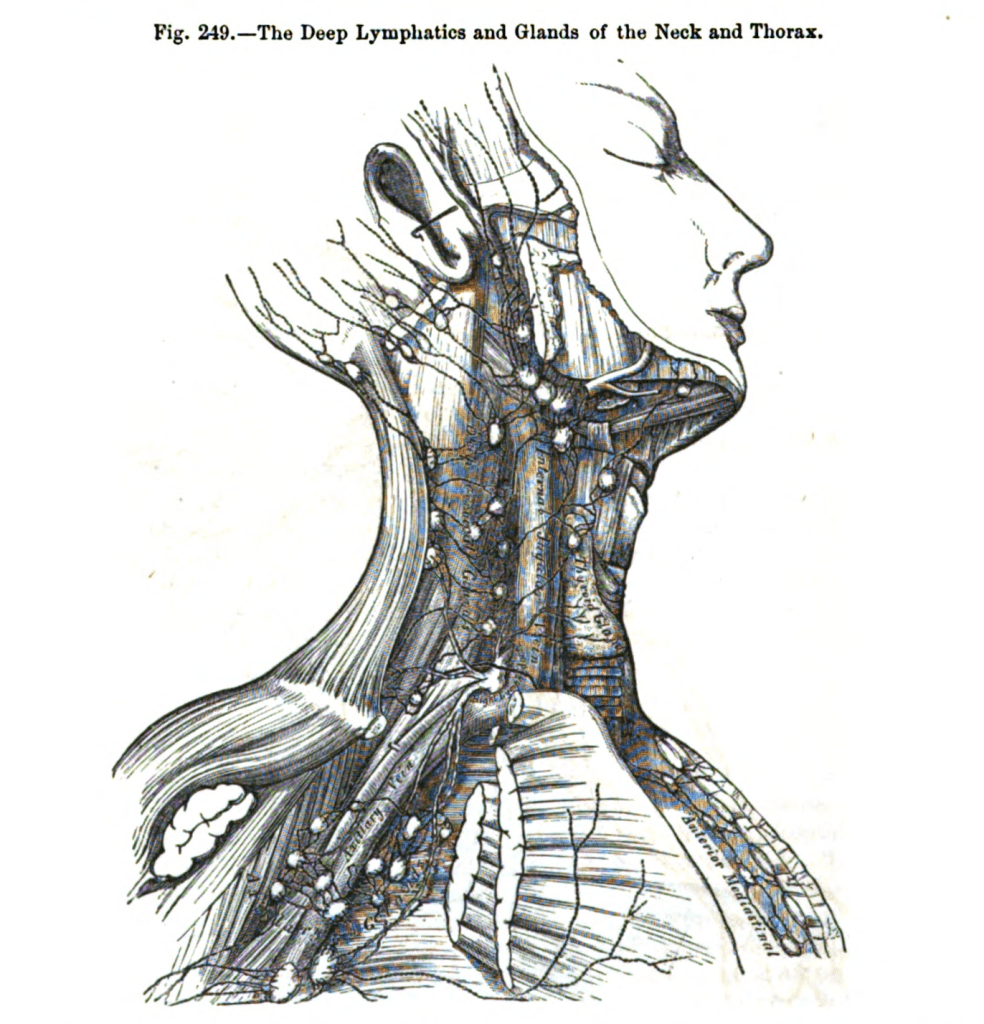

Anatomy, Descriptive and Surgical was first published in 1858. The author, Dr. Henry Gray, had intended to create an “accurate view of anatomy” for students and practitioners, for the application of practical surgery. This work was to be an inexpensive textbook from the mind of the celebrated wunderkind, who had already been published, celebrated, and named a Fellow of the Royal Society by the age of only 25.

For the illustrations, Gray re-teamed with Dr. Henry Vandyke Carter, another anatomist/surgeon who was a skilled anatomical artist. Their previous collaboration had been Gray’s 1854 book, On the Structure and Use of Spleen. The new work was to be their biggest collaboration yet. Unfortunately it was also their last: Gray died in 1861 of smallpox, contracted from caring for his nephew. Before his passing, he had completed a second edition of his Anatomy that corrected minor mistakes and added illustrations by a Dr. Westmacott.

Since its original publication in 1858, the book succeeded in both its original purpose and became culturally synonymous with the profession. Descriptive and Surgical Anatomy became a key text, although now the title was shortened to Gray’s Anatomy, both easier to say and in honor of the author. Editions of the book were not just for professionals either. It became part of the Western canon. For example, performance artist Spalding Gray used the title for his one-man piece, later a Steven Soderbergh film, in which he muses on his options after being diagnosed with a rare ocular disease.

The title has never gone out of print. The key textbook even adapted with technology. Back in 2005, as the 39th edition of Gray’s Anatomy was set to be published, one could purchase a virtual edition for an additional $60. At the same time, another Gray—or rather, Grey—would take over the cultural context….

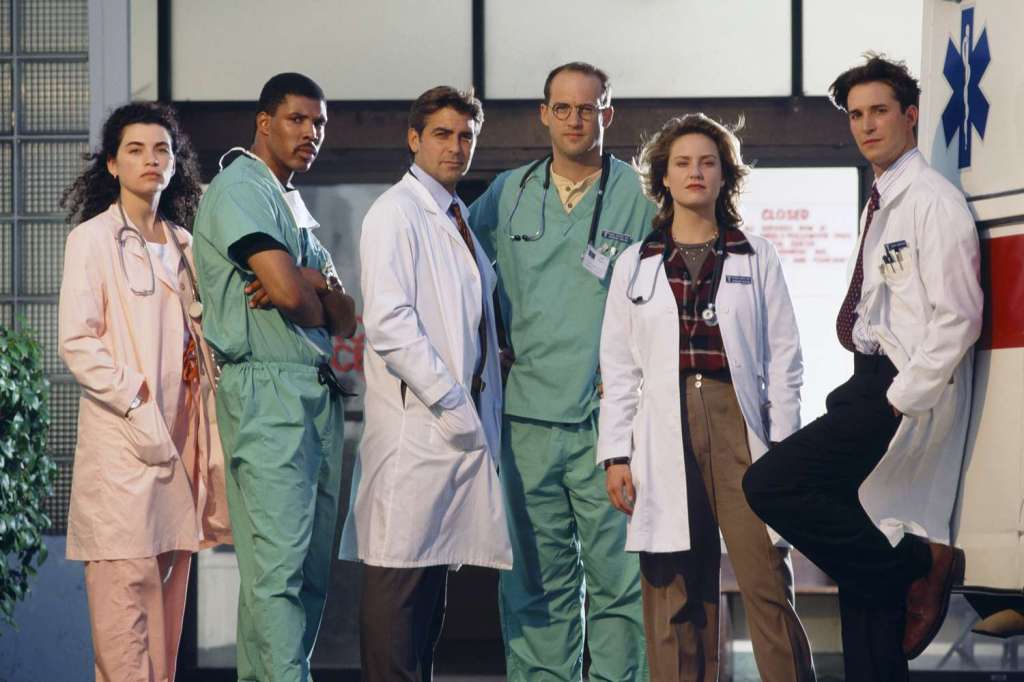

There was no shortage of doctors on television. ER (1994–2009) was created by writer Michael Crichton. Although he never obtained his medical license, Crichton had graduated with his MD from Harvard Medical School. Crichton first scripted ER in the 1970s with the idea of making it a film. It reflected the rotations he took part in. When it was filmed in 1994 as a two-hour television pilot, not much was changed. During his short-lived medical career, he had become disenchanted with how corporate he believed medical care had become. ER is set in the fictional, financially tight, Cook County General Hospital in Chicago. Crichton’s mind-set comes through in some of his other work, including the (also) hospital-set, body-snatching horror film, Coma.

ER set a gold standard for hospital dramas. Crichton believed that for the first time on television they provided “realism” of what things were like an emergency room. Subsequent hospital television would have to do something different. This led to a more stylized approach as it went on for Chicago Hope (1994–2000). Scrubs (2001–2010) was different in that it was a comedy that mixed in the reality of the job. Then there were the countless unsuccessful rip-offs that couldn’t find their own unique voice, lasting one season or less. Plus, for early seasons, ER had up and coming actor George Clooney as part of their cast. He would go on to be one of the biggest names in Hollywood.

House, MD premiered in 2004 on FOX and starred British actor Hugh Laurie as the titular, misanthropic doctor. Creator David Shore looked to Sherlock Holmes as inspiration for his character. House gave his patients and viewers a methodical approach to his diagnoses, which were, more often than not, some rare disease, disorder, or occurrence. House had managed to give the medical yet another new take.

In 2005, ABC didn’t show much confidence in their latest pilot. It was another medical drama. They couldn’t even agree on a name: Complications, Surgeons, Miss Diagnosis, Grey’s Anatomy, it didn’t matter. They believed nothing they could top ER, which was still a ratings and critical juggernaut ten years in. But they were riding high after successfully rolling out two dramas in the last year, Desperate Housewives and Lost.

First-time creator Shonda Rhimes believed she had a show that would once again break a hospital-set mold. She tended to associate hospitals with “good things.” It was the place where they would “fix” you. Rhimes understood that there had to be a balance between that sentiment and the real lives that those who worked there had. “They’re just people at work.”

With those intentions in mind, executive producer Peter Horton tried to keep it looking “real.” He wanted the characters to look worn out; it’s a tough job! He wanted them to be unglamorous, with little to no make-up. This is most evident in the first episode. They found that even getting real-looking scrubs on the actors wouldn’t make for must-see tv, so they pivoted to it the reality rest on the emotional heft of being in a hospital. The remaining eight episodes of the abbreviated first season reflected that.

Those who worked on the show were skeptical. “It’s doctors with teenage dialogue,” Thomas Burman, a special effects makeup artist recalled thinking. Initial reviews were mixed, including people stating that the show needs “a brain.” Entertainment Weekly had reservations but overall found it enjoyable. ABC could take a loss if this, in their eyes, “generic” mid-season replacement (never a good sign in television terms) fizzled out.

On March 27th, 2005, the first episode of Grey’s Anatomy, “A Hard Day’s Night,” premiered at 10pm, following a season two episode of Desperate Housewives. Audiences were introduced to the main character and narrator, Meredith Grey (Ellen Pompeo), as she and her intern cohort endured their first 48 hours at Seattle Grace. Meredith’s voiceovers give context and comfort. (Coincidentally, a different Gray, Henry Gray, offered a similar “welcoming tone” in the earlier editions of his Anatomy, according to Bill Hayes’s The Anatomist. Unlike Meredith Grey’s, Henry Gray’s voice was taken out of later editions.) Meredith continues to narrate today, 20 seasons in. The episode was the most-watched mid-season premiere in years.

Over the course of the next few weeks, the fervor for Grey’s Anatomy only grew. It was originally only intended to have a four-week run in the coveted post Housewives Sunday slot. ABC kept it for the rest of the season. It would air on Sundays again for the second season, which was even bigger, including a whopping 27 episode order. The stars including Pompeo, Sandra Oh, Katherine Heigl, and Chandra Wilson experienced career highs. There was a career resurgence of 80s teen heartthrob, Patrick Dempsey. Grey’s Anatomy also added to the cultural vernacular! “McDreamy,” Grey’s name for her on-again, off-again lover, Dr. Derek Shepherd (Dempsey), changed the 80’s “Mc-” critique of capitalism to something (or someone) that is craved.

Two years into its run, Andrew Holtz, MPH, wrote a book on the intricate science featured on House, MD. Seeing the success of the other popular doctor show, he wrote The Real Grey’s Anatomy in 2010. As a faculty member, he was given the opportunity for intimate access to the lives of medical students and the patients in care at Oregon Health and State University (OHSU). Grey’s Anatomy was used as the framework to show what reality is like and what a fictional show gets right—or gets wrong. Holtz apologized to fans who were seeking more in-depth analysis of their favorite program.

In the introduction to Holtz’s book, a fourth-year resident laments, “None of them have bags under their eyes…. That is so far away from the reality of interns.” As accurate to “reality” as the show wants to be, especially Peter Horton’s original concerns on their glamour, Grey’s Anatomy is first and foremost a consumer product. Justin Chambers, who played original intern Alexander Karev, notes that “we need to be appointment television every week.” This is why you have event episodes, like the season two, post—Super Bowl bomb scare two-parter, and why difficult surgeries go hand in hand with the complicated interpersonal conflicts the characters go through. It’s art! The show employs medical advisers, and writers work with the objective to only tell stories that have a recorded case. From there, they can tell the story however they want, even if it makes those advisers “roll their eyes” or “pull their hair out”! Real medical terminology has to be learned by the actors, which sometimes is harder for them than a whole monologue.

Grey’s Anatomy continues to be popular as it enters twenty years on air and will conclude its 21st season sometime in May 2025. We know it continues to be one of the most watched shows. Are doctors part of this audience too?

Doctors mention they may get the occasional real-life question that they see stemming from the show. In 2013 Cosmopolitan offered a q+a with a GP, Dr. Emma Wilding, who was asked about some of the more “out there” instances. She was happy to oblige.

Author Eric Berger looked into the television doctor effect for Annals of Emergency Medicine and concluded that while the occasional patient misunderstanding may occur, the show served to open up a dialogue between doctor and patient. If we’re to continue to fight misunderstanding and create personable communication between medicine and people, perhaps having the staff of Seattle Grace—or as it was renamed, Grey Sloan Memorial—as our allies benefits everyone.

References:

“ER.” Michael Crichton. Published February 3, 2023. Accessed March 25, 2025. https://www.michaelcrichton.com/works/er/

Berger, E. “From Dr. Kildare to Grey’s Anatomy.” Annals of Emergency Medicine, Volume 56, Issue 3, A21 – A23. 2010.

Gray, Henry. Anatomy, Descriptive and Surgical. First American Edition. Blanchard and Lea; 1859.

Gray, Henry. Anatomy, Descriptive and Surgical. Second American Edition. Blanchard and Lea; 1862.

“Gray’s Anatomy, 39th Edition: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice.” AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26(10):2703-2704.

Hayes, Bill. The Anatomist : A True Story of Gray’s Anatomy. Bellevue Literary Press; 2009.

Holtz, Andrew. The Real Grey’s Anatomy. Penguin; 2010.

Jacobs J. Body Trauma TV. British Film Institute; 2003.

Rhodes J. “Thriving Ratings for a New Patient on ABC.” New York Times. Published April 14, 2005. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2005/04/14/arts/television/thriving-ratings-for-a-new-patient-on-abc.html

Rice, L. How to Save a Life. St. Martin’s Press; 2021.

Silvers, I. “I asked an actual doctor if Grey’s Anatomy is like real life and this is what she said.” Cosmopolitan. Published September 6, 2017. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://www.cosmopolitan.com/uk/entertainment/a12019073/are-medical-dramas-like-real-life/