by Anthony Murisco, Public Engagement Librarian

On February 8th, 2021, the city of Boston was celebrating in a big way. For Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler’s 190th birthday, the city had decided to declare the entire day in her honor. Despite this high honor, many still do not know who she is.

The largest newspaper in Boston, The Boston Globe, introduced readers to the local hero’s story in February 2020. At the time, Crumpler and her second husband, Arthur, were buried in an unmarked grave. Noting the significance of Crumpler, the first Black female doctor in the United States, the local Hyde Park Historical Society teamed up with the Friends of the Hyde Park Library to raise money for a proper headstone.

A follow-up in July of the same year informed the readers of a ceremony held to unveil the memorial. It also helped give a little more insight into the life of Dr. Crumpler; born Rebecca David in 1831, she was raised in Pennsylvania by her aunt. While growing up, she was shown what it meant to be a caretaker as she saw her aunt provide care for those in their neighborhood. She left for Charlestown, Massachusetts, and married her first husband, Wyatt Lee, in 1852. From working as a nurse from 1852–1860 for various doctors and their letters of recommendation, she was accepted into the New England Female Medical College.

In the middle of her schooling, her husband passed away from tuberculosis. She graduated in 1864 as the first Black woman in the United States to do so, as well as the only Black woman to graduate from New England Female Medical College before it merged with another medical school in 1873. The following year, she married Arthur Crumpler. They settled and spent the rest of their lives in Hyde Park, a neighborhood in south Boston. In her 1883 book, A Book of Medical Discourses: In Two Parts, Dr. Crumpler opens with a dedication; “To Mothers, Nurses, and all who may desire to mitigate the afflictions of the human race, this book is prayerfully offered.” The Boston Globe article mentions how she faced plenty of adversity in her profession, including white pharmacists who refused to fill scripts signed by her. Despite all of this, nothing could stop her from helping the people who needed her.

Rewriting History

It wasn’t her own education, in the very same area where Crumpler once walked, that taught Boston University Medical School student Dr. Melody McCloud about this pioneer. Rather it was when, freshly graduated, she moved to Atlanta, Georgia, around 1981. There she learned about Dr. Crumpler and the Rebecca Lee Society, an organization made up of Black female physicians. Speaking on Crumpler and other forgotten physicians, McCloud told the Boston Globe, “There are a lot of accomplishments of Blacks that are left out of the history books.”

In her 2013 book, Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race, writer Margot Lee Shetterly coined the titular term. The “hidden figures” in her story are three Black women, Mary Jackson, Katherine Johnson, and Dorothy Vaughan, who were instrumental in bringing the first astronauts into space. Despite being crucial to the team, they were hardly spoken of. Shetterly uncovered the story through talking to those who were there. From Johnson, she learned of Jackson; through Jackson, she got to Vaughan. The stories are passed down through the people who lived it and with the help of communities like the Rebecca Lee Society. With Shetterly’s help, Hidden Figures has been able to inspire others. It was even made into a movie! What can we do to these other “hidden” heroes?

In 2020 national attention was given to the Crumplers’ Hyde Park memorial thanks to NBC Nightly News. Since then, Dr. Crumpler and her accomplishments are being recognized more and more. Symposiums are now being held in her honor, the first being at Boston University School of Medicine in conjunction with her 190th birthday. She also began popping up in an unlikely place: children’s picture book biographies.

Her Own Image

Writers and illustrators have become masterful in non-fiction storytelling for kids. . Some of these books are storytime staples. The illustrations bring history and people back to life. Can it be done for someone who has no surviving pictures?

If you were to do an image search for “Rebecca Lee Crumpler,” you’d get some results. Unfortunately, none of these is the woman you are looking for! Despite commercial photography coming of age during her lifetime, any images of her have been lost to time. She is often mistakenly identified as other Black women, including Mary Eliza Mahoney. Boston University’s student-run newspaper made this mistake in its coverage of Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler Day, and eventually retracted and rectified its error, one of the few to do so.

Given the absence of portraits, how can you project this person?

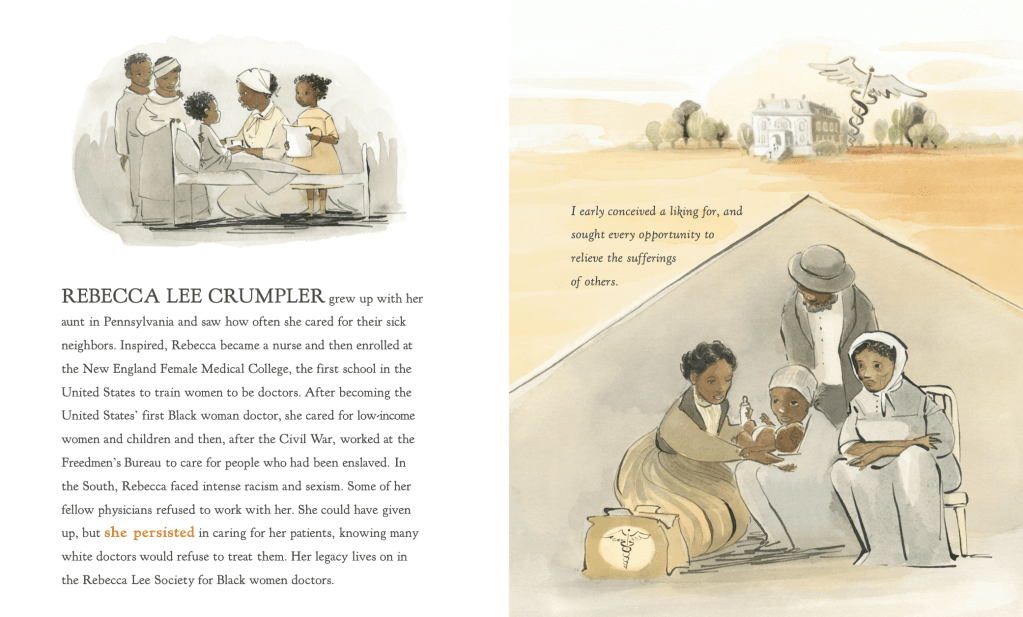

Alexandra Boiger has showed us the lives of many historical and contemporary women as the illustrator of Chelsea Clinton’s She Persisted series. For She Persisted in Science, Boiger was able to pictorialize Crumpler’s life based on her research on the “physical and emotional” state of those at the time. Boiger told the Library, via e-mail, that she was “always trying to balance the harshness of the time with the heart and love of the people and Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler herself.” Her images succeed in showing the care that, as Crumpler herself wrote, she was striving for.

Shani Mahiri King’s 2024 book Finding Rebecca is both an ode to Crumpler and an act of research. From studying Crumpler and the lives of 19th-century Black Americans, he worked with his illustrator, Nicole Tadgell, to show us how she may have lived. Tadgell herself is an accomplished illustrator with a slew of historical picture books under her belt. King paired his own findings with the direct words of Crumpler from Medical Discourses, not only to tell her story but to inspire others.

King believes that more history is just waiting to be uncovered: hidden figures, histories, legends, all ready to have their stories told. The book ends with a call to action: “You too are a historian, you too are an author, and you too can help teach all of us about people who should be more famous than they are.”

References:

“Changing the Face of Medicine | Rebecca Lee Crumpler.” Nih.gov, 3 June 2015, cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_73.html. Accessed 26 Feb. 2025.

Clinton, Chelsea. She Persisted in Science. Penguin, 1 Mar. 2022.

Crumpler, Rebecca Lee. A Book of Medical Discourses, in Two Parts. 1883. Boston, Cashman, Keating, printers, collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-67521160R-bk.

Jonas, Anne. “Boston Honors Rebecca Lee Crumpler Day — First Black Woman in the US to Receive Medical Degree.” The Daily Free Press, 8 Feb. 2021, dailyfreepress.com/2021/02/08/boston-honors-rebecca-lee-crumpler-day-first-black-woman-in-the-us-to-receive-medical-degree/. Accessed 26 Feb. 2025.

King, Shani Mahiri. Finding Rebecca. Tilbury House Publishers and Cadent Publishing, 15 Oct. 2024.

MacQuarrie, Brian. “Gravestone Dedicated to the First Black Female Medical Doctor in the US .” BostonGlobe.com, The Boston Globe, 17 July 2020, http://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/07/17/metro/gravestone-dedicated-first-black-female-medical-doctor-us/. Accessed 26 Feb. 2025.

Rechtoris, Mary. “Hidden Figures’ Margot Lee Shetterly: How Writing Is a Lot like E-Discovery.” Relativity, 16 Jan. 2020, http://www.relativity.com/blog/hidden-figures-margot-lee-shetterly-how-writing-is-a-lot-like-e-discovery/. Accessed 26 Feb. 2025.

Sweeney, Emily. “Fundraising Effort Underway in Hyde Park to Honor Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler, First Black Woman to Earn Medical Degree in US.” BostonGlobe.com, The Boston Globe, 10 Feb. 2020, http://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/02/10/metro/fundraising-effort-underway-hyde-park-honor-dr-rebecca-lee-crumpler-first-black-woman-earn-md-degree-us/. Accessed 26 Feb. 2025.