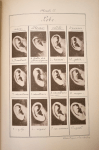

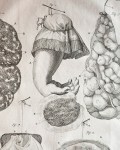

I was so excited to finally have the opportunity to pore over a book in the NYAM collection which I had long admired from afar: Jacques Gamelin‘s beautiful and lavish Nouveau recueil d’osteologie et de myologie (“New collection of osteology and mycology”) of 1779. This book, as explained to me by Arlene Shaner—acting curator and reference librarian for historical collections, at NYAM—was intended as a large scale, deluxe manual for artists interested in understanding human anatomy in order to create more convincing depictions of human figures.

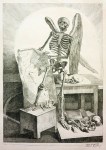

The meat of the book, as it were, is a collection of extremely virtuosic anatomical renderings (12-15) showing skinned—or écorché—human figures in a variety of poses. But what is much more interesting—at least to me—is the assortment of animated skeletons which fill the opening pages; these fanciful figures are engaging in such activities as waking up in a cemetery to the trumpet of the resurrection (text reading: surgite mortui venite ad judicium, or “Rise up, come to the judgment of the dead”; image 6); brandishing anatomical drawings in what looks to be a dissection room littered with bones (3); and raping and pillaging the parties of fashionably bewigged lords and ladies (9, 10). I am also very drawn images playing on biblical themes, such as a calm Saint Bartholomew being flayed alive (an old staple of anatomical illustration; image 11), and a skinned and anatomized Christ on the cross (12) which evokes this more literal rendition, cast from a convicted murderer just a few decades after this book was published.

Interestingly, Gamelin is best remembered today not for this book, but as a painter and engraver of battle scenes, genre scenes, and portraits. He dedicated this book to his mentor, a certain Baron de Puymaurin (image 1 and 2), who had recognized Gamelin’s artistic abilities and funded his training when his father refused to do so. It is thought that Gamelin funded the book himself after inheriting a great deal of money upon his father’s death, which perhaps accounts for its delightful eccentricity.

- Gamelin 2

- Gamelin 3

- Gamelin 4

- Gamelin 5

- Gamelin 6

- Gamelin 7

- Gamelin 8

- Gamelin 9

- Gamelin 10

- Gamelin 11

- Gamelin 12

- Gamelin 13

- Gamelin 14

- Gamelin 15

This post was written by Joanna Ebenstein of the Morbid Anatomy blog, library and event series; click here to find out more.