By Sheryl Wombell, University of Cambridge, and the Library’s 2024 Audrey and William H. Helfand Fellow.

In seventeenth-century Europe, knowledge about health and healing was shared with family, friends, and acquaintances. In the case of printed books, wider audiences were reached. A significant subset of these communications took the form of recipes: sets of instructions telling one how to make something. These might be instructions for making medicines in the home, with a range of ingredients from the inexpensive and easily sourced, to the rare and exotic products available due to expanding trade. Or they could be instructions to make culinary formulations, which were interpreted as having an impact on the body’s condition due to the lasting influence of the ancient theory of the four humours. Individual recipes, which could be as short as a line or as long as tens of pages, were gifted, traded, and passed around early modern social networks.

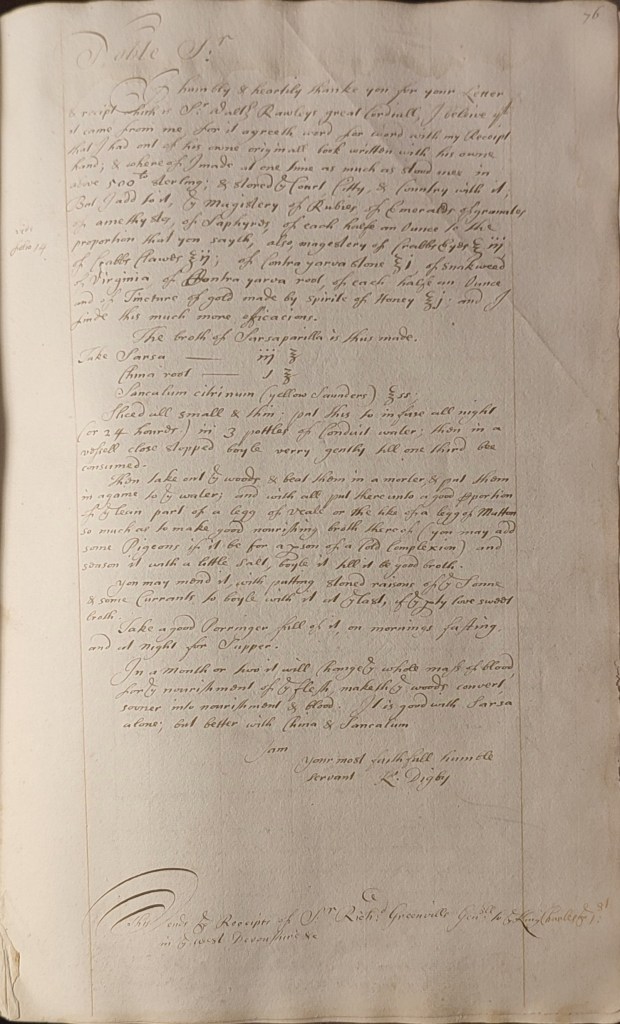

A letter penned by the courtier and privateer Sir Kenelm Digby, likely to Sir Richard Grenville, 1st Baronet of Kilkhampton, demonstrates the mobility of recipes in the mid-seventeenth century.i In it, Digby thanks Grenville for sending him a recipe for ‘Sir Walter Rawleys great Cordiall’ but questions its provenance:

I beleive th[a]t it came from me, for it agreeth word for word with my Receipt that I had out of his owne originall book written with his owne hand; & whereof I made at one time as much as stood mee in above 500 [pounds] sterling; & stored the Court, Citty, & Country with it; But I add to it, the Magistery of Rubies, of Emeralds of granales of amethystes, of Saphyres, of each halfe an Ounce to the proportion that you sayth, also, magestery of Crabbs Eyes [3 oz], of Crabbs Clawes [2 oz]; of Contra yarva stone [1 oz], of snakweed of Virginia, of Contra yarva root, of each halfe an Ounce and of Tincture of gold made by spirite of Honey [1 oz]; and I finde this much more efficacious.

The circular path of recipes that Digby describes – when a recipe he believes to be his own is unwittingly returned to him – is testament to the lively early modern traffic in recipe dissemination and collection.

Manuscript collections of recipes survive in archives around the world, and the New York Academy of Medicine Library holds a rich cache of such volumes. Thanks to winning their Helfand Fellowship in 2024, I had the privilege of spending five weeks on a close reading of the early modern medical recipe collections at NYAM. This research forms part of my PhD project, which looks at the mid-seventeenth century production, management, and transmission of knowledge about health and healing amongst exiled and mobile elites, including Digby. While my work to date had focused on three key media – printed medical books, manuscript recipe collections, and consultation letters – somewhat in isolation from each other, at NYAM I had the time and resources to explore the relationships between these formats.

One such connection was the integration of transcribed letters into larger manuscript collections. Digby’s letter, for example, was copied into a large bound volume of recipes, letters, and transcriptions from printed books titled ‘Old Doctor 1690’. But in handling the manuscripts I was also confronted with material traces of transmission. In another manuscript, for example, is a recipe for ‘Costiveness to help’, that is, how to relieve constipation. Next to the instructions are two small, shiny blobs of dried red sealing wax. While this is not conclusive evidence that the recipes on the page were copied into a letter, it does indicate that the notebook lay open while a letter was sealed – and likely written – in its vicinity. Through this tiny physical sign, we learn something of the co-presence of writing and collecting practices across the distinct but interrelated media of letters and recipe books.

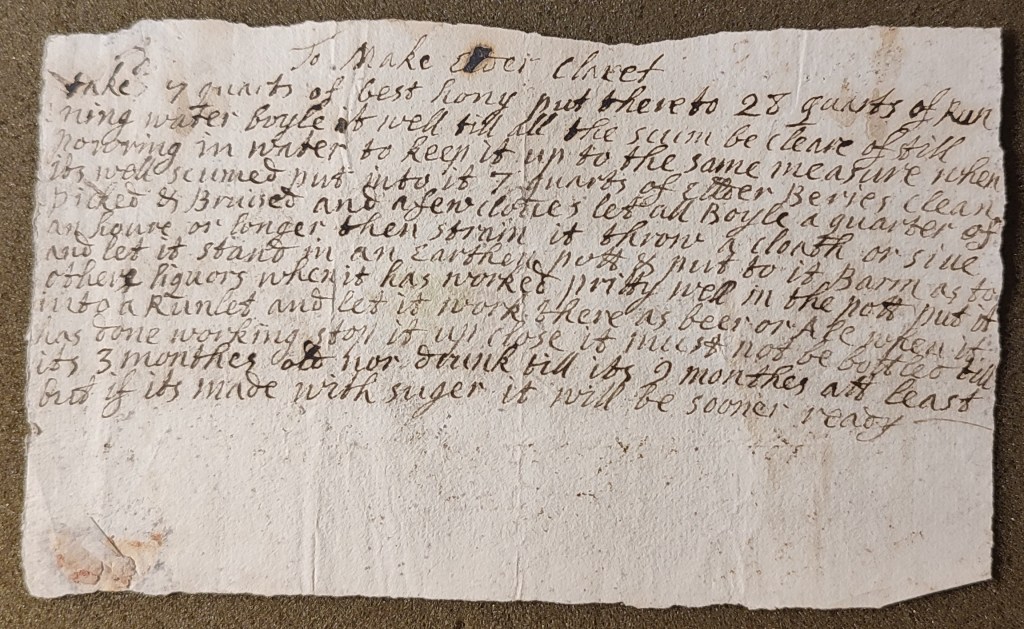

The objects of transmission themselves also appear in these recipe collections. A notebook belonging to Owen Salesbury holds a loose paper slip with instructions ‘To Make Elder Claret’ and sent ‘To Mrs Longford att her hous in Wrexham’. Folded slips could be enclosed in a larger letter, or they could constitute the entire missive. The inclusion of the address on this example suggests the latter. The contents of the slip were not transcribed into the body of the notebook but containing it within the bound volume preserved its knowledge. We don’t know precisely how or when a slip sent – or intended to be sent – to a Mrs Longford ended up in Salesbury’s manuscript, but it offers further evidence of the close connections between ephemeral letter formats and the more durable objects of recipe collections.

Spending time in the NYAM Library’s collections allowed me to get to grips with evidence of early modern recipe transmission. While digitised surrogates of manuscripts have been invaluable in my research, handling these collections has enriched my analysis by bringing their material qualities – size, varying durability, the spatial relationships between their contents, and signs of use – to the fore.

Further Reading:

Ken Albala, Food in Early Modern Europe (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2003).

James Daybell, The Material Letter in Early Modern England: Manuscript Letters and the Culture and Practice of Letter-Writing, 1512–1635 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

Elaine Leong, Recipes and Everyday Knowledge: Medicine, Science, and the Household in Early Modern England (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2018).

Alisha Rankin, ‘Recipes in Early Modern Europe,’ Encyclopedia of the History of Science (2023), https://doi.org/10.34758/fvw2-w336.