by Anthony Murisco, Public Engagement Librarian

As the April showers (hopefully) dwindle down, out come May flowers. The passage of the month means the conclusion of April’s celebrations, including National Poetry Month, and the commencement of the festivities of May, including National Dental Care Month. We’re going to combine both, with a poem by a dental care worker.

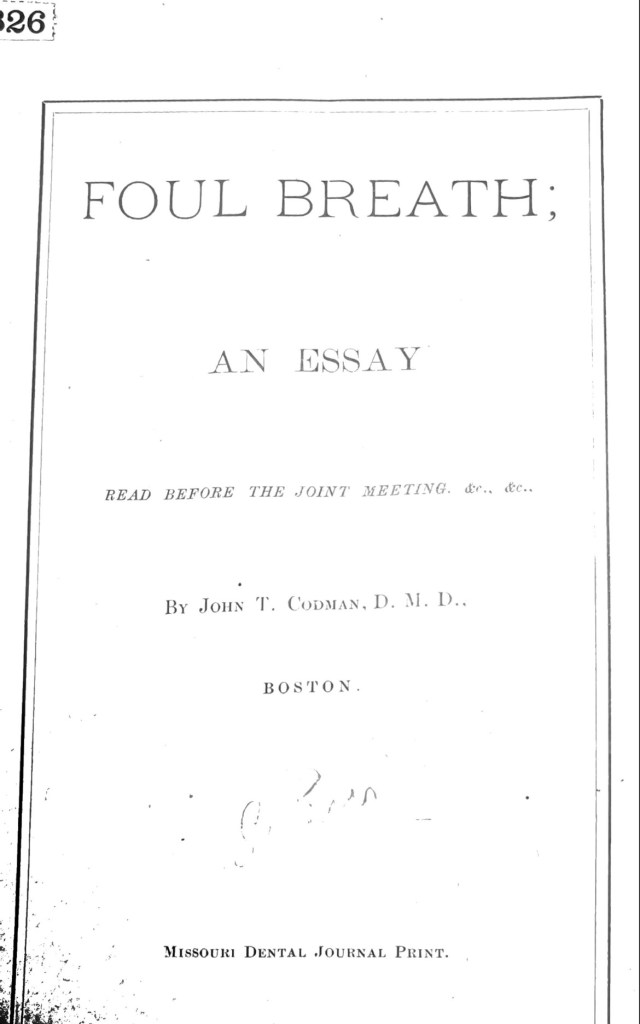

John Thomas Codman (d. 1907) was the an active speaker at various dental gatherings. He was also one of the more prolific writers on dentistry. But he wrote about more than teeth and dental issues. Dr. Codman’s writing appeared in mass market publications and he wrote about the co-op community he belonged to in the 1894 book, Brook Farm, Historic and Personal Memoirs.

Codman broke a sensitive issue when he wrote his essay, “Foul Breath.” When speaking on the problem, he hinted at dentistry’s higher involvement with the human body; “I cannot but think that the neglect is occasioned by want of that knowledge of its primary causes, and a lack of general knowledge of the relation of all the organs, one to another, that work together for the sustenance and maintenance of the life and health of all of our corporate frames.” His words call for a well-rounded, holistic approach to the whole profession. Really, who knew one could wax so poetic about bad breath?

Well, if you were at the 1866 meeting of the American Dental Association, you would know. In the Doric Hall of the State House in Boston, Dr. Codman welcomed the guests with a poem encompassing the birth and battles fought by our nation. It includes dental puns and nods to popular attractions in Boston. He even manages to add in a few pop culture references!

Today we bring you a slightly abridged version of this welcome poem.

The Dentists’ Welcome.

Welcome, ye knights of the forcep and plugger,

The Bay State invites, embrace her and hug her;

Her arms are outstretched, and her years not so few,

That her check might mantle with blushes anew;

The friends of her dear sons from near and from far,

To her impulses pure, how welcome they are.

So, friends, from the West take a chair and sit down,

In the capitol old of this capital town;

In the hall where the “assembled wisdom” meet,

When the winter comes in with its flying sleet,

And leave only when the tubers begin to grow,

And shoots of the corn are too old for the crow.

‘Ecod, what is that which hangs high in mid air?

My professional friend, no wonder you stare;

‘Tis the ghost of a fish, long salted and sold,

But never like Hamlet’s, shall its tale unfold;

‘Tis a pity, for if he was minded to blow,

And tell all he knows of the actions below,

The “lately Departed” would wriggle and squeak,

And some heads, like curs’ tails, be drooping and weak;

He’d prove to us all what we know not before,

That men could be made of nothing but jaw.

Ye friends from the East, as ye trod the rotunda,

Saw yet the battle-flags rent all asunder?

Uncover! Bow low! For those stains are of blood

Of the martyrs that fell by field and by flood.

Ah! Could but th enote of the trumpet again

Awake the departed by hill and by plain,

And turn back the tide of the nation’s great day,

With the blot on its banner of slavery, say,

Who would sound it? Lives there such a man now?

Then shrivel his muscles and wrinkle his brow;

His right arm be palsied and dried up by his tongue,

In lines most accursed let his name be sung.

Rest, martyrs, the sound of battle is o’er,

And your feet tread soft on the Elysian shore.

Ye who come from North, Easy, South, and “far West,”

Our programme is ready, so join in with zest.

Here’s Liberty’s “cradle,” where the babe was rocked,

Such a naked little thing that the nurse was quite shocked.

She has grown pretty large since that time you’ll say,

And larger still grows with the flight of each day.

New members she’s had, and as everyone knows,

The president adds daily V. toes and V. toes.

There’s Breed’s hill, called Bunker’s where the boys had a fight,

What there is left of it, just a very small mite,

With a big pile of stones on it, so it shan’t blow away,

And to commemorate a sort of Bull Run in its day,

Only the bull didn’t run on that eventful morn,

And the Yankee boys’ pluck took the bull by the horn.

Here’s Harvard beyond, the famed “seat of learning”

For lads who are able to keep the torch burning;

The poor must digest what the schoolmaster teaches,

Driven in at the head and seat of the breeches.

Here’s Agassiz’s museum of fishes and bones,

With birds, beasts and reptiles, plants, skeletons, and stones,

And many other things that deserve your attention,

As the auctioneer says, “too numerous to mention.”

Here’s the Natural History, with molusks and “crusty”

Pickled snakes done in bottles, and specimens musty;

Here’s a good chance to “compare” the jaw-bones of owls,

With the dodo and eagle, and all sorts of fowls;

Here you can sit on a “rush-bottom” and study with ease

Whether the walrus eats pork, or the elephant cheese;

Here’s molar teeth, to pull would take forceps immense,

Got up, like the drama, at unlimited expense.

But now let us hasten, the mastodon waits;

Just imagine the creature wearing two pair of skates,

Gliding about on thick ice in the river;

Should the cold climate his carcase make shiver,

The Yankees might “guess” that his heartiest shake

Was a touch of the long-remembered earthquake.

Here’s the footprints of birds, tremendous “Shanghies,”

That could life young pigs high and dry from their sties,

And swallow them whole, spite of any protest,

With paving stones plenty to make them digest.

We’ll look at the Hospitals, City and State;

Should fortune be right, or unfortunate fate,

We need not the privilege seek for or beg

Of seeing the surgeon “make a hand of a leg.”

If Paddy could jest thus, why can’t I declare

That oft a broken arm is a humerus affair.

‘Twould take paper and ink by the ton, more’s the pity,

To tell all the wonders to be seen in our city;

So I shan’t do it, but let you explore for yourselves,

And lay up your treasures on memory’s fair shelves.

Then there’s the serious part, the weighty discussion,

The clash of ideas in serious concussion;

The din of the clinic with twenty filled chairs,

And the usual amount of splitting of hairs.

There is delegate 1, with wisdom erratic,

And delegate 2, with mallet automatic;

Like Uriah Heep, here’s a chair that can tumble

From dignified straight-back to posture most “’umble;”

But to make the thing equal, and state it right fair,

The owner is sure to set a “heap” by his chair.

…………………

My welcome is most done—it’s no welcome that tires–

And I fear that I keep you from other desires.

And now for a breath of the saltiest sea air,

A dip and a splash in Venus’ deep lair;

The steamer is ready, we wait not the oar,

Strike up, sweetest music,– away goes the shore!

Now let the gay laugh grow louder and louder,

As sweet on the nostril comes smell of the chowder;

Here’s filling to put in—there’s plate-work enough here

To last a smart dentist to the end of the year.

Success to him, say I, he fortune can win

Whose filling, in spite of the water, stays in.

With great hopes for our future, for peace while we stay,

May the star of the dentist mount high into day,

Is my wish; so, therefore, to part in good cheer,

One little conundrum I’ll venture just here.

Why is the dentist, when fishing, I pray,

Engaged in the trade he follows each day?

Can’t guess it, you say, you slyest of vulpines–

Because he, no double, will pull out some skull-pins.

Some of Dr. Codman’s other writings can be found in our collection. You can also find there’s a lot of poetry written by medical professionals. To see for yourself, contact library@nyam.org for an appointment.

References:

“John Thomas Codman Brook Farm collection,” Harvard Library,https://hollisarchives.lib.harvard.edu/repositories/24/resources/3381, accessed April 30, 2024.

Codman, John T. Foul Breath. Boston, 1879.

Codman, John Thomas. Welcome poem: to the members of the American Dental Association. Boston : Wright & Potter, 1866.