By Dr. Michael Robinson, National Army Museum Research Fellow, University of Birmingham (UK), and the Library’s 2024 Paul Klemperer Fellow in the History of Medicine

I spent one month working in the New York Academy of Medicine’s magnificent library and reading room in the autumn of 2024. This residency enabled me to look at a host of materials dedicated to the treatment of mentally ill American Army veterans of the First World War during the Great Depression (1929–1939). I undertook this research hoping to utilise the USA as an important comparative case study on my current research project dedicated to mental illness and British Great War veterans during the 1930s. By examining mental breakdown and psychiatric medical care during this decade, this research seeks to reveal the delayed traumatic after-effects of war service on ex-service personnel and the potential for additional psychosocial determinants to influence mental ill-health.

I first became interested in the American experience of post-First World War disability and mental healthcare owing to its regular appearance in the archival records of Britain’s Ministry of Pensions, the government agency responsible for distributing veterans’ pensions and medical care. During the inter-war period, British policymakers regularly cited the US experience of veteran after-care as a deterrent and a case study to avoid replicating. They actively held up the US system as being unfairly exclusive, costly, and liberal owing to its incremental but costly expansion of veteran rights and facilities. Britain significantly reduced its liability on behalf of veterans during the 1920s and 1930s, including the closure of most veterans’ hospitals. Veterans’ medical care in Britain was primarily outsourced to broader public health facilities, the civilian welfare state, and the charity sector.

By contrast, the US witnessed increased state liability, including a vast financial outlay in funding exclusive Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals and medical facilities. In 1936, owing to the two nations’ inversed approaches to veteran care, one Ministry of Pensions official described the UK and US responses as being of ‘opposite extremes.’1 The primary purpose of my time at the NYAM was to better understand why the British and US systems were the complete inverse of one another. I also sought to appreciate how these contrasting policy trajectories and medical infrastructures affected the lives of mentally ill veterans.

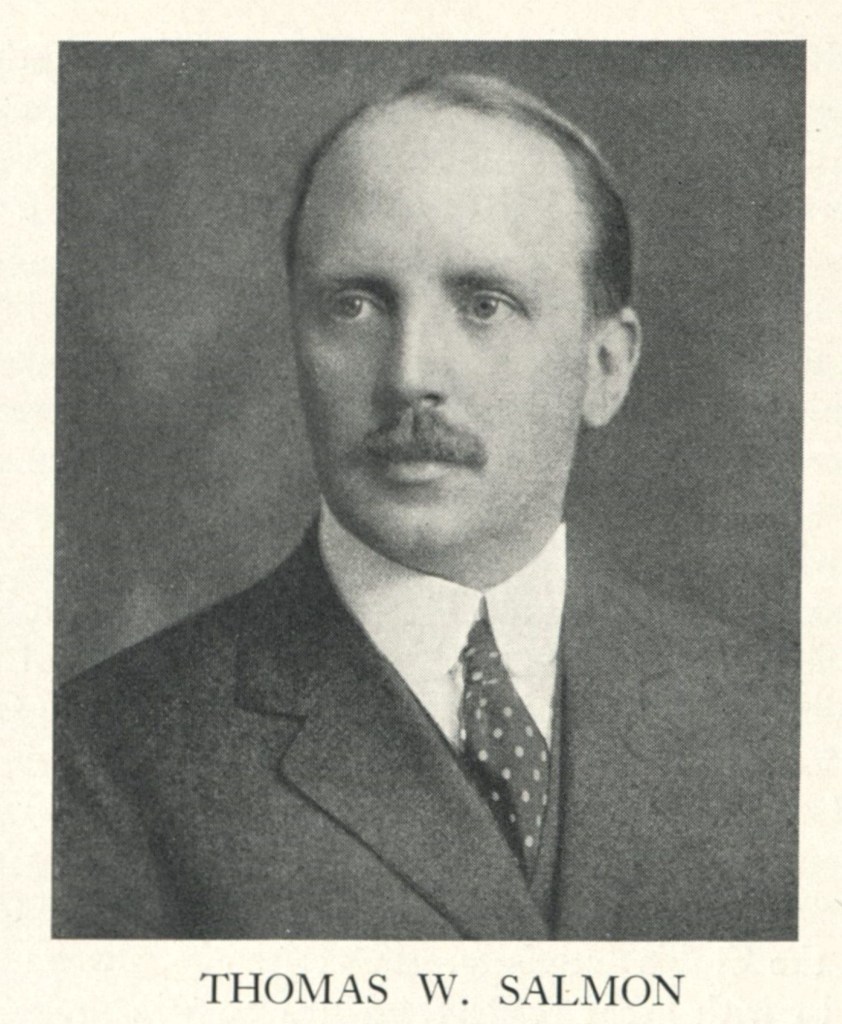

This comparative approach first led me to NYAM records relating to Dr. Thomas Salmon (1876–1927). For those unfamiliar, Salmon was the American Expeditionary Forces’ chief consultant in psychiatry during the First World War. Before this important role, following the country’s entry into the global conflict in 1917, Salmon visited England to study how it dealt with mental wounds during the war to help inform his country’s approach.2 As a leading figure in the US National Hygiene Movement before and after his war service, the records of Salmon’s war experience reflect a relatively progressive military medical official. He regularly stressed the environmental causes of soldiers’ breakdown. In short, Salmon was more inclined to blame combat neurosis and stress on the dehumanising and brutalising effects of war service than citing faulty hereditary genetics, as was more apparent amongst British military officials. This more empathetic outlook continued into Salmon’s advocacy on behalf of veterans following his return to America. Unlike the more reclusive and disillusioned Dr. Charles Myers, the British Army’s leading psychiatric official, Salmon advocated for healthcare and welfare on behalf of the mentally disabled First World War veterans during the initial post-war years. Described by his biographer as a successful ‘spokesman for veterans,’ the force of Salmon’s personality and his effective collaboration with the American Legion help explain why the American mentally ill veteran stopped being admitted into larger public mental hospitals.3 Instead, the US Federal Government established exclusive medical facilities for veterans from the early 1920s onwards.

Salmon died unexpectedly whilst sailing near Long Island in 1927. Reflecting his prestige amongst his contemporaries, the National Committee for Mental Hygiene, an advocacy organization founded in 1909 by Clifford W. Beers, set up the Salmon Committee on Psychiatry and Mental Hygiene at the New York Academy of Medicine in 1931.4 Regardless, the exclusive medical infrastructure he had helped establish continued to cater to mentally ill First World War veterans into the 1930s. In stark contrast to Britain’s minuscule and dwindling psychiatric infrastructure, the VA provided seventeen neuropsychiatric facilities across its national network of forty-nine hospitals. It offered 10,633 beds for mental ailments, marking a 467% increase over 1921’s availability. The number of beds would be set to increase for the rest of the decade.5 With this exclusive federal medical care program for veterans, the VA published its Medical Bulletin journal throughout the 1930s. Pouring through these issues reveals a lively forum of VA medical officials discussing the continued difficulties of treating veterans during this period.

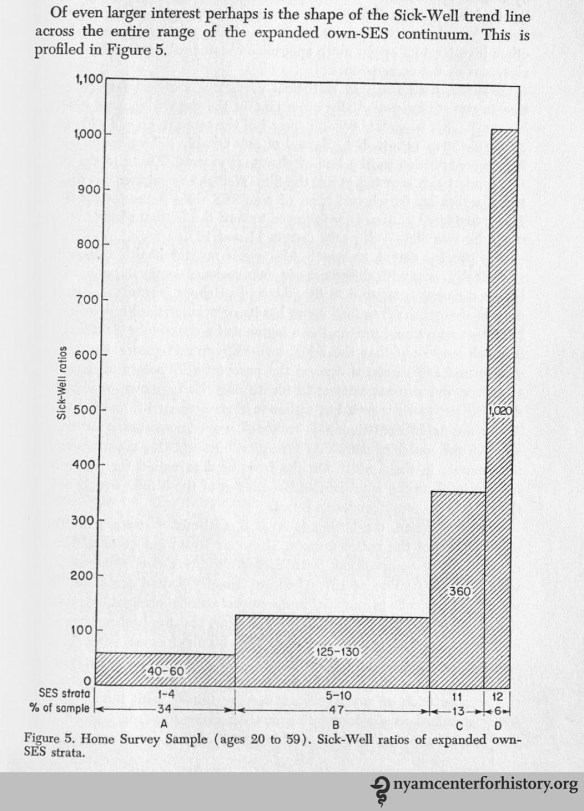

Regarding neuropsychiatry—I was struck by how hospital superintendents, nurses, vocational trainers, and social workers regularly articulated a holistic approach to mental healthcare. They cited the psychosocial determinants of health outside of hospital walls. This includes, for example, the detrimental impact of unemployment and poverty on an individual’s mental and bodily health, the emasculating stigma attached to male mental illness, and the potential for harmful self-medication practices such as alcoholism.

The materials I reviewed at the NYAM provide a complex and nuanced picture of the post-war treatment of mentally ill World War One veterans. On the one hand, they give an image of an expansive, caring and financially generous veterans’ system. On the other hand, however, they provide comparatively little insight into the personal perspectives of veteran patients to verify the progressive narrative offered by medical officials. In addition, contemporary medical journals reveal increasing resentment from American citizens regarding the spiralling costs of veteran medical care with little in return in terms of cure and recovery.6 This counter-narrative also appears worthy of further research.

Before arriving in New York, I was unsure how exactly the USA would fit into my larger project of Great War veterans during the Great Depression. However, my time at the NYAM proved incredibly rewarding by revealing how fascinating and unique an American case study is. I look forward to continuing this research into 2025.

Notes:

1 Nineteenth Annual Report of the Ministry of Pensions, 1935-1936, 33.

2 For a write-up of Salmon’s observations and recommendations, see Thomas Salmon, The care and treatment of mental diseases and war neuroses (“shell shock”) in the British Army (War Work Committee of the National Committee for Mental Hygiene, 1917).

3 E. D. Bond, Thomas W. Salmon: Psychiatrist (W. W. Norton & Co, 1950), 160.

4 For more information on the Salmon Committee on Psychiatry and Mental Hygiene and its records that are held in the NYAM, see https://www.nyam.org/library/collections-and-resources/archives/finding-aids/ARN-0006.html/ [last accessed 18 November 2024].

5 E. O. Crossman and Glenn E. Myers, ‘The neuropsychiatric problem in the US Veterans’ Bureau,’ Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 94, no. 7 (1930), 473–478.

6 For example, see the Crossman and Myers article cited above.