By Rebecca Pou, Project Archivist

To celebrate National Poetry Month, we are sharing a poem from our collection each week during April.

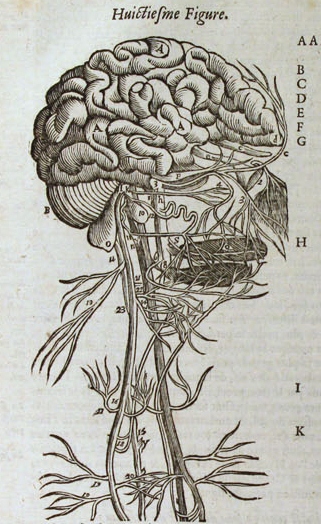

Syphilis seems like an unlikely topic for a poem, yet it is the subject of an important and popular work. Syphilis, or the French Disease, was first published in 1530. At that time, syphilis was new to Europe and spreading fast. To the Italians it was the “French disease,” to the French the “Italian disease,” with many other countries blaming one another for bringing the infection to their citizens. Written in Latin by the multi-faceted Italian physician and poet Fracastorius, the poem was translated into many languages, reflecting the great desire to understand this disease. Our collection holds multiple editions, including the original, pictured above, and several English versions (this post features two English translations – one is pictured below and another as the excerpts).

In the poem, which is broken into three parts, we learn of the disease and some popular treatments of the time, including mercury and the plant remedy guaiac. We also read the tale of a shepherd named Syphilus, supposedly the first person afflicted with the disease, which was his punishment for spurning the sun. Excerpts from each of the poem’s books, taken from William Van Wyck’s translation, are below.

Book 1

Within the purple womb of night, a slave,

The strangest plague returned to sear the world.

Infecting Europe’s breast, the scourge was hurled

From Lybian cities to the Black Sea’s wave.

When warring France would march on Italy,

It took her name. I consecrate my rhymes

To this unbidden guest of twenty climes,

Although unwelcomed, and eternally.

………………

O Muse, reveal to me what seed has grown

This evil that for long remained unknown!

Till Spanish sailors made west their goal,

And ploughed the seas to find another pole,

Adding to this world a new universe.

Did these men bring to us this latent curse?

In every place beneath a clamorous sky,

There burst spontaneously this frightful pest.

Few people has it failed to scarify,

Since commerce introduced it from the west.

Hiding its origin, this evil thing

Sprawls over Europe

………………Book 2

Soon is repaired the ruin of the flesh,

If lard be well applied that’s good and fresh,

Or dyer’s colors of a soothing power.

If some poor soul, impatient for the hour

Of sweet release, should find too slow this cure,

And yearning for a quicker and more sure,

Then stronger remedies without delay

Shall kill this hydra another way.

………………

All men concede that mercury’s the best

Of agents that will cure a tainted breast.

To heat and cold sensitive’s mercury,

Absorbing the fires of the this vile leprosy

And all the body’s flames by its sheer weight…

………………Book 3

An ancient king had we, Alcithous,

Who had a shepherd lad called Syphilus.

On our prolific meads, a thousand sheep,

A thousand kine this shepherd had to keep.

One day, old Sirius with his mighty flame,

During the summer solstice to us came,

Taking away the shade from all our trees,

The freshness from the meadow, coolth from breeze.

His beasts expiring, then did Syphilus

Turn to this horror of a brazen heaven,

Braving the sun’s so torrid terror even,

Gazing upon its face and speaking thus:

‘O Sun, how we endure, a slave to you!

You are a tyrant to us in this hour.

………………

The sun went pallid for his righteous wrath

And germinated poisons in our path.

And he who wrought this outrage was the first

To feel his body ache, when sore accursed.

And for his ulcers and their torturing,

No longer would a tossing, hard couch bring

Him sleep. With joints apart and flesh erased,

Thus was the shepherd flailed and thus debased.

And after him this malady we call

SYPHILIS, tearing at our city’s wall

To bring with it such ruin and such a wrack,

That e’en the king escaped not its attack.

………………