By Lisa O’Sullivan, Director, Center for the History of Medicine and Public Health

Whew!

Our first Festival of Medical History and the Arts was a great success; more than 1,000 people attended and responded enthusiastically to our mix of talks, demos, films, etc. Now that we have had a chance to draw breath, here are a few details from the day:

It’s hard to pick highlights, although of course Dr. Oliver Sacks speaking about his intellectual influences and the patients who inspired his Awakenings was hugely exciting for all of us. We are grateful to Dr Sacks and all the speakers who came and shared their knowledge.

Our guest curators did an amazing job. Lawrence Weschler’s Wonder Cabinet started with a (big) bang, a banjo-accompanied cosmic/neuronal slapdown, and ended with fascinating insights from Riva Lehrer into how an artist’s body can affect her art and her anatomy teaching. In between, spectators had the chance to get a glimpse into the experience of having an epileptic fit; share anatomical adventures; and witness some cringe-inducing treatments suffered by monarchs through the ages.

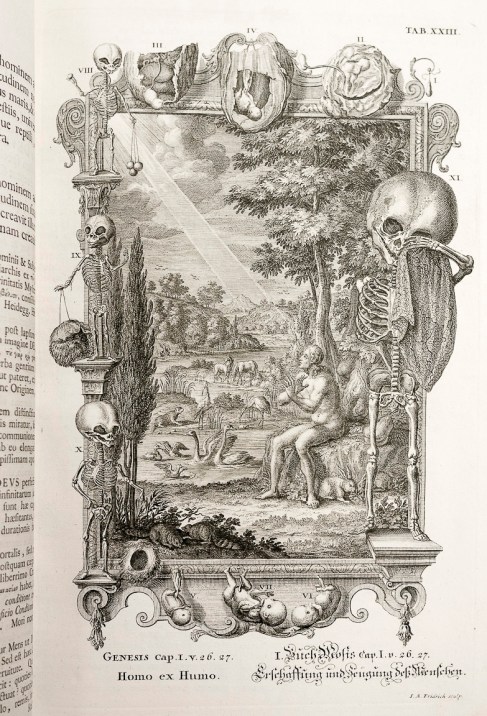

Joanna Ebenstein’s Morbid Anatomy presentation of 12(!) talks throughout the day were standing-room only, forcing us to move to a larger room, which filled up just as quickly. The day started with Mexican traditions around death, took a detour to human zoos, wax anatomical models, medical library pleasures, memento mori, and skull theft before ending with the little-discussed practice of bookbinding with human skin.

Our conservation team prepared a wonderful exhibit of models demonstrating development of the book over time (no human skin involved), as well as a whimsical look at the life of miniature books. We put highlights from our collections on display, and welcomed visitors to our conservation laboratory. Meanwhile, visitors could learn the art of making anatomical wax moulage and see Gene Kelly struggle with combat fatigue. And the after party cocktails and cartoons were just the things needed to wind down after the long day.

With so many people, some events did fill up. Particular apologies to those who couldn’t make it on a behind-the-scenes tour. With such overwhelming demand, we’re planning to make them a much more regular feature, so if you missed out you’ll get another chance at a future event. Our two anatomical workshops were also full; for those of you in New York, we are investigating offering courses on a more regular basis, so please let us know if you are interested!

Pictures from the day are up on our Facebook page, and winners of the caption competition and the raffle will be announced soon. Meanwhile, keep an eye out for more details of our Performing Medicine mini-fest, coming in the spring. Hope to see you then, if not before for some of our stand-alone events!