Food historian Stephen Schmidt wrote today’s post, which includes findings from research he conducted at NYAM last summer. The post was originally posted on the Recipes Project blog.

Food writers who rummage in other people’s recipe boxes, as I am wont to do, know that many modern American families happily carry on making certain favorite dishes decades after these dishes have dropped out of fashion, indeed from memory. It appears that the same was true of a privileged eighteenth-century English family whose recipe book now resides at the New York Academy of Medicine (hereafter NYAM), under the unprepossessing label “Recipe book England 18th century. In two unidentified hands.” The manuscript’s culinary section (it also has a medical section) was copied in two contiguous chunks by two different scribes, the second of whom picked up numbering the recipes where the first left off and then added an index to all 170 recipes in both sections.

The recipes in both chunks are mostly of the early eighteenth century—they are similar to those of E. Smith’s The Compleat Housewife, 1727—but a number of recipes in the first chunk, particularly for items once part of the repertory of “banquetting stuffe,” are much older. My guess is that this clutch of recipes was, previous to this copying, a separate manuscript that had itself been successively copied and updated over a span of several generations, during the course of which most of the original recipes had been replaced by more modern ones but a few old family favorites dating back to the mid-seventeenth century had been retained. Among these older recipes, the most surprising is the bread crumb gingerbread. A boiled paste of bread crumbs, honey or sugar, ale or wine, and an enormous quantity of spice (one full cup in this recipe, and much more in many others) that was made up as “printed” cakes and then dried, this gingerbread appears in no other post-1700 English manuscript or print cookbook that I have seen.

And yet the recipe in the NYAM manuscript seems not to have been idly or inadvertently copied, for its language, orthography, and certain compositional details (particularly the brandy) have been updated to the Georgian era:

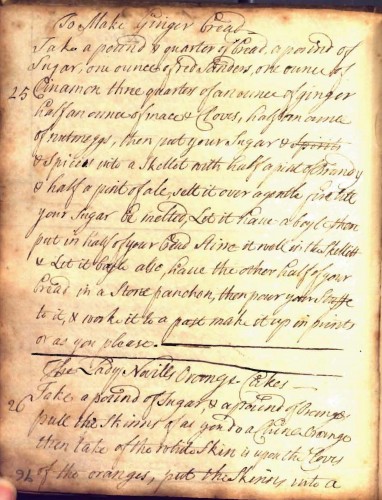

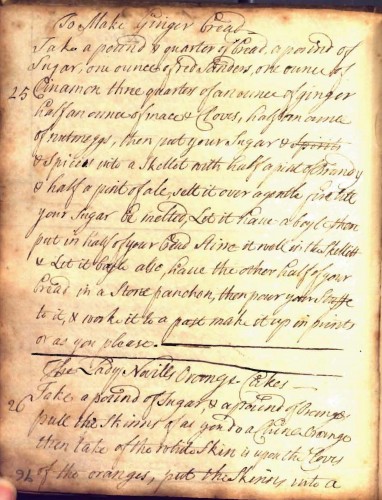

25 To Make Ginger bread

Take a pound & quarter of bread, a pound of sugar, one ounce of red Sanders, one ounce of Cinamon three quarters of an ounce of ginger half an ounce of mace & cloves, half an ounce of nutmegs, then put your Sugar & spices into a Skillet with half a pint of Brandy & half a pint of ale, sett it over a gentle fire till your Sugar be melted, Let it have a boyl then put in half of your bread Stirre it well in the Skellet & Let it boyle also, have the other half of your bread in a Stone panchon, then pour your Stuffe to it & work it to a past make it up in prints or as you please.

Eighteenth-century recipe book, England.

From the fourteenth century into the mid-seventeenth century, bread crumb gingerbread was England’s standard gingerbread (for the record, there was also a more rarefied type) and, by all evidence, a great favorite among those who could afford it—a fortifier for Sir Thopas in The Canterbury Tales, one of the dainties of nobility listed in The Description of England, 1587 (Harrison, 129), and according to Sir Hugh Platt, in Delightes for Ladies, 1609, a confection “used at the Court, and in all gentlemens houses at festival times.” Then, around the time of the Restoration, this ancient confection apparently dropped out of fashion. In The Accomplisht Cook, 1663, his awe-inspiring 500-page compendium of upper-class Restoration cookery, Robert May does not find space for a single recipe.

The reason for its waning is not difficult to deduce. Bread crumb gingerbread was part of a large group of English sweetened, spiced confections that were originally used more as medicines than as foods. Indeed, the earliest gingerbread recipes appear in medical, not culinary, manuscripts (Hieatt, 31), and culinary historian Karen Hess proposes that gingerbread derives from an ancient electuary commonly known as gingibrati, whence came the name (Hess, 342-3). In England, these early nutriceuticals, as we might call them today, gradually became slotted as foods first through their adoption for the void, a little ceremony of stomach-settling sweets and wines staged after meals in great medieval households, and then, beginning in the early sixteenth century, through their use at banquets, meals of sweets enjoyed by the English privileged both after feasts and as stand-alone entertainments.

Through the early seventeenth century banquets, like the void, continued to carry a therapeutic subtext (or pretext) and comprised mostly foods that were extremely sweet or both sweet and spicy: fruit preserves, marmalades, and stiff jellies; candied caraway, anise, and coriander seeds; various spice-flecked dry biscuits from Italy; marzipan; and sweetened, spiced wafers and the syrupy spiced wine called hippocras. In this company, bread crumb gingerbread, with its pungent (if not caustic) spicing, was a comfortable fit. But as the seventeenth century progressed, the banquet increasingly incorporated custards, creams, fresh cheeses, fruit tarts, and buttery little cakes, and these foods, in tandem with the enduringly popular fruit confections, came to define the English taste in sweets, whether for banquets or for two new dawning sweets occasions, desserts and evening parties. The aggressive spice deliverers fell by the wayside, including, inevitably, England’s ancestral bread crumb gingerbread.

As the old gingerbread waned, a new one took its place and assumed its name, first in recipe manuscripts of the last quarter of the seventeenth century, and then in printed cookbooks of the early eighteenth century. This new arrival was the spiced honey cake, which had been made throughout Europe for centuries. It is sometimes suggested that the spiced honey cake came to England with Royalists returning from exile in France after the Restoration, which seems plausible given the high popularity of French pain d’épice at that time—though less convincing when one considers that a common English name for this cake, before it became firmly known as gingerbread, was “pepper cake,” which suggests a Northern European provenance. Whatever the case, Anglo-America almost immediately replaced the expensive honey in this cake with cheap molasses (or treacle, as the English said by the late 1600s), and this new gingerbread, in myriad forms, became the most widely made cake in Anglo-America over the next two centuries and still remains a favorite today, especially at Christmas.

By the time the NYAM manuscript was copied, perhaps sometime between 1710 and 1730, molasses gingerbread was already ragingly popular in both England and America, and evidently the family who kept this manuscript ate it too, for the second clutch of culinary recipes includes a recipe for it, under the exact same title as the first. Remembering the old adage that the holidays preserve what the everyday loses, I will hazard a guess that the old gingerbread was made at Christmas, the new for everyday family use.

150 To Make Ginger Bread

Take a Pound of Treacle, two ounces of Carrawayseeds, an ounce of Ginger, half a Pound of Sugar half a Pound of Butter melted, & a Pound of Flower. if you please you may put some Lemon pill cut small, mix altogether & make it into little Cakes so bake it. may put in a little Brandy for a Pepper Cake

Recipe book England 18th century.

An interesting question is why the seventeenth-century English considered the European spiced honey cake sufficiently analogous to their ancestral bread crumb gingerbread to merit its name. It may have been simply the compositional similarity, the primary constituents of both cakes being honey (at least traditionally) and spices. Or it may have been that both cakes were associated with Christmas and other “festival times.” Or it may have been that both cakes were often printed with human figures and other designs using wooden or ceramic molds. Or it may possibly have been that both gingerbreads had medicinal uses as stomach-settlers. In both England and America, itinerant sellers of the new baked gingerbread often stationed themselves at wharves and docks and hawked their cakes as a preventive to sea-sickness. (Ship-wrecked off Long Island in 1727, Benjamin Franklin bought gingerbread “of an old woman to eat on the water,” he tells us in The Autobiography.) One thinks at first that the ginger and other spices were the “active ingredients” in this remedy, and certainly this is what nineteenth-century American cookbook authors believed when they recommended gingerbread for such use. But early on the remedy may also have been activated by the treacle. Based on the perhaps slender evidence of a single recipe in E. Smith, Karen Hess proposes that the first English bakers of the new gingerbread may have understood treacle to mean London treacle (Hess, 201), the English version of the ancient sovereign remedy theriac, a common form of which English apothecaries apparently formulated with molasses rather than expensive honey. I have long wondered what, if anything, this has to do with the English adoption of the word “treacle” for molasses (OED). Perhaps a medical historian can tell us.

Works Cited

Harrison, William. The Description of England. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1994

Hess, Karen. Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery. New York: Columbia University Press, 1981.

Hieatt, Constance and Sharon Butler. Curye on Inglysch. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

“Treacle, I. 1. c.” The Compact Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1991.

Stephen Schmidt is the principal researcher and writer for The Manuscript Cookbooks Survey, an online catalogue of pre-1865 English-language manuscript cookbooks held in the U. S. repositories, which will launch in early 2013. He is the author of Master Recipes, a 940-page general-purpose cookbook, was an editor of and a principal contributor to the 1997 and 2006 editions of Joy of Cooking, has contributed to The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink and Dictionnaire Universel du Pain, and has written for Cook’s Illustrated magazine and many other publications. A resident of New York City, he works as a personal chef and a cooking teacher and hopes soon to complete Lemon Pudding, Watermelon Cake, and Miracle Pie, a history of American home dessert.

a. Pest remediation instrument. The small nozzle can reach into the gutters of books, and capture crawling insects and larva via suction. They are whisked into the clear chamber, where they will peacefully expire in the oxygen deprived environment.

a. Pest remediation instrument. The small nozzle can reach into the gutters of books, and capture crawling insects and larva via suction. They are whisked into the clear chamber, where they will peacefully expire in the oxygen deprived environment.