By Anthony Murisco, Public Engagement Librarian

The French Quarter is at the heart of New Orleans. This area is known for its unique architecture. A blend of traditions from its former colonizers, France and Spain, bred a new style. Fires and other calamities since the 18th century may have destroyed most of the original buildings, but a distinct style remains in the neighborhood.

Following the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, New Orleans experienced an influx of people from other states, eager to seize new opportunities. Louisiana and, of course, New Orleans were now part of the United States of America. New rules brought forth new laws. Under the rule of their new country’s leaders, medicine, for one, could only be practiced and administered by licensed professionals.

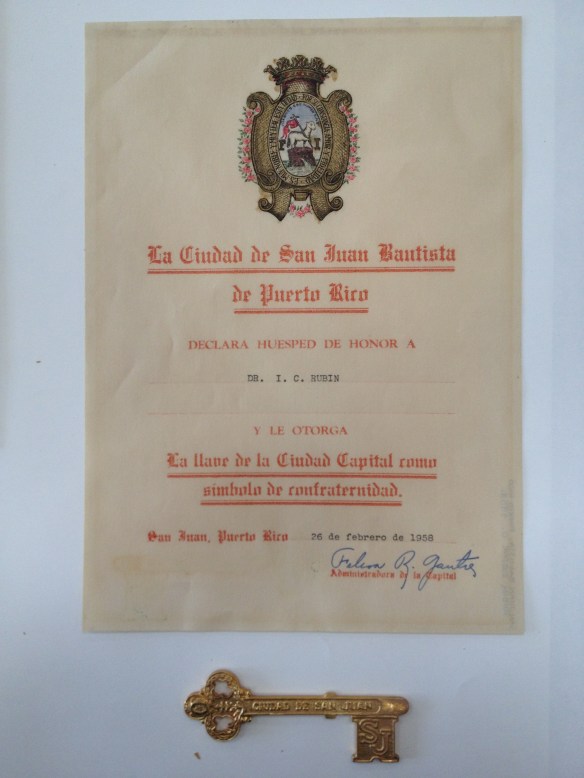

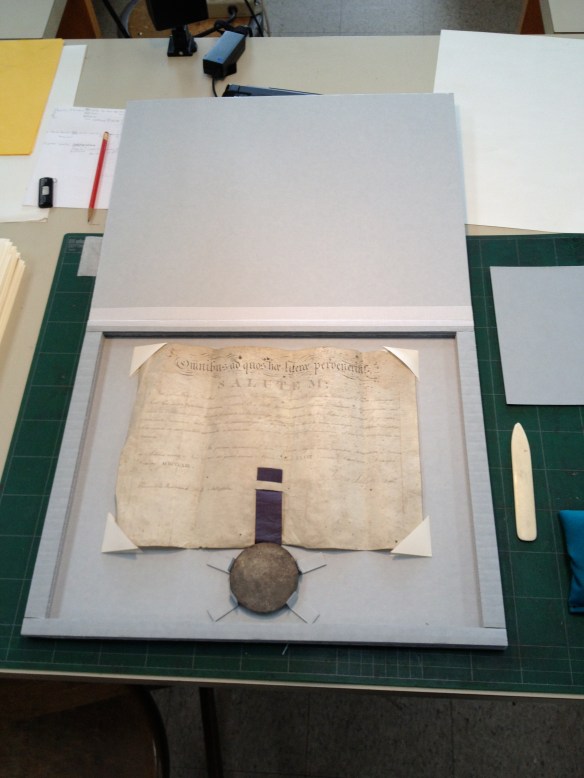

The Board of Pharmacy of the new state of Louisiana granted its first certificate to Louis J. Dufilho Jr. in May of 1816. Dufilho was not only the first Louisianan to do this but also the first licensed pharmacist in the entire United States. In 1823, he and his family came to the French Quarter to establish their pharmacy. From 1823 until 1855, Dufilho served the people of this fast-growing American port.

In April of 2025, over 200 years later, a group of us gathered outside a building on a hot New Orleans day. Although the building was going through a brief period of routine touch-ups, it still stood out. A sign with a mortar and pestle declares “Le Pharmacie Française,” with a sign below indicating that this is indeed the “Historical Pharmacy Museum.”

This is the home of the New Orleans Pharmacy Museum at 514 Chartres Street. We were welcomed not only by our tour guide but also by a giant soda fountain from 1855. The decommissioned soda pump still holds the necessary ingredients needed to make proper medicinal concoctions. Before the tour officially started, we were allowed to roam and explore the first floor. New Orleans’ early relationship to the history of a pharmacy was about to be unspooled for us. Our packed crowd consisted of residents from many different states and an entire family from Ireland.

There are two types of tours available here: a self-guided tour, complete with a text guide to help you understand the collection, or a group tour led by a tour guide. The historian we were fortunate enough to have as our tour guide helped bring the sights we were seeing to life. It has been proven that creating an engaging lesson increases the likelihood of retaining that knowledge.

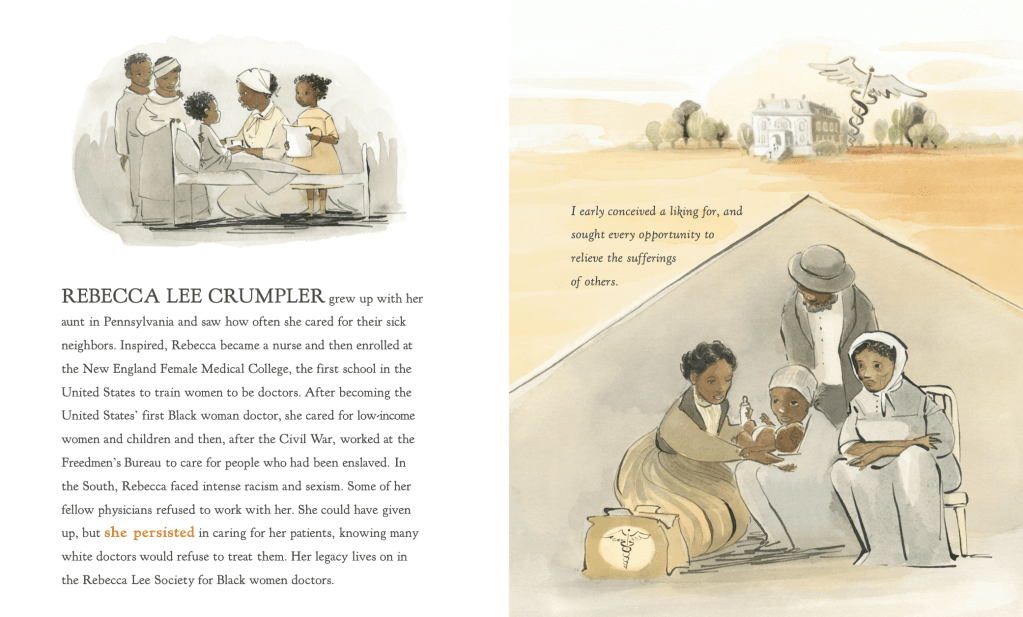

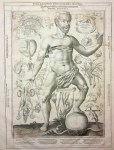

The Pharmacy Museum doesn’t shy away from the realities of the early pharmacy industry. What could easily come across in a sensationalized manner—to engage visitors or promote clicks—is given context. The way they present their material fosters a dialogue with what we know now. In 2018, the Museum even commissioned local artist Kate Lacour to create an illustrated guide to items from their permanent collection. Do No Harm reminds us not to scoff at earlier treatments; the goal has always been healing.

During my visit, something struck me about seeing physical copies of the items I had previously read about. I have seen countless advertisements and trade cards discussing the wonders of Lydia E. Pinkham’s treatments, and now some items were in front of me!

This harmony between museums and libraries furthers understanding. The item that I read about is authentic, and that item, which I see before my very eyes, has a history we can explore inside a book.

At the end of the tour, our guide asked us to look at the slate floor we had been on the whole time. She informed us that the floor has not changed since Dr. Dufilho and his family resided there, some 200 years ago! She left us with this thought so that we could think about all those who had also set foot in the building over the years. Knowing what we learned about the evolution from house to historical building, for what purposes had these people come the way that we had?

As we approach summer, with vacation and/or time off approaching, take a moment to think about what you might want to learn more about. Whether you’re visiting an entirely different country, a different state, or even staying local and opening a book, there are plenty of stories waiting to be shared.

References:

Lacour, Kate. Do No Harm. Antenna Press, 2018.