In conjunction with its exhibit, “Extraordinary Women in Science & Medicine: Four Centuries of Achievement,” the Grolier Club is holding a symposium on October 26, 2013, to which all are welcome. The exhibition and symposium explore the contributions of 32 women, one being Florence Nightingale, to science and medicine. The exhibition features NYAM’s copy of one of Nightingale’s statistical charts. In today’s blog post, Natasha McEnroe, director of London’s Florence Nightingale Museum, explains their significance.

The Victorians loved nothing better than to measure and classify, trying to discover natural laws through the data they recorded, and Florence Nightingale (1820-1910) was no exception in sharing this general enthusiasm. Having gained celebrity status from her nursing work at the infamous Barracks Hospital at Scutari, the British base hospital in the Crimean War (1853-1856), Nightingale returned to England with her health permanently broken down. Determined that the appalling treatment of the soldiers during the war should not be repeated, she spent the rest of her life conducting a political campaign for health reform from her bedroom. One of the ways her campaigning was groundbreaking was in the use of statistics.

St Thomas’ Hospital, London, home of the Nightingale Training School for nurses. Reproduced courtesy of the Florence Nightingale Museum.

Nightingale’s love of mathematics was apparent from an early age and was an interest encouraged by her father, who took the responsibility of educating his daughters into his own hands. Her parents’ social circle brought the young Nightingale into contact with many of the most brilliant minds of the age, including Charles Babbage, whose own passion for numbers (and not a little pedantry) is shown in a letter to Alfred Tennyson in response to the poem The Vision of Sin:

‘In your otherwise beautiful poem, one verse reads,

Every moment dies a man,

Every moment one is born.…If this were true, the population of the world would be at a standstill. In truth, the rate of birth is slightly in excess of that of death. I would suggest that the next version of your poem should read:

Every moment dies a man,

Every moment 1 1/16 is born.

Strictly speaking, the actual figure is so long I cannot get it into a line, but I believe the figure 1 1/16 will be sufficiently accurate for poetry.’

Just weeks after her return from the Crimean War in 1856, Nightingale secured a Royal Commission from Queen Victoria investigating the health of the British Army. Nightingale herself was involved in every step of the Commission’s investigations, working with the statistician William Farr to illustrate graphically that more British troops died of disease during the war than in battle. Farr encouraged Nightingale to compare statistics on mortality rates of civilians with that of soldiers, showing that whether at war or at home, soldiers demonstrated a higher mortality rate. He wrote to Nightingale, “This I know…Numbers teach us whether the world is ill or well governed.” Nightingale pioneered what is now called evidence-based healthcare and in 1858 she was the first woman elected to the Royal Statistical Society.

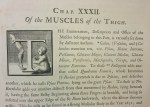

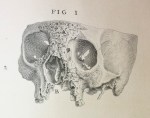

Chart from NYAM’s copy of Florence Nightingale’s A contribution to the sanitary history of the British army during the late war with Russia (London, 1859).

A devout woman, Nightingale saw statistics as having a spiritual aspect as well as being the most important science, and believed statistics helped us to understand God’s word. Influenced by the ethos of Victorian vital statistics, her greatest legacy can be seen in improved public health, reformed nursing education, and in her innovative polar area graphs and other work in statistics. In Nightingale, this most eminent of Victorians, we can see the combination of the two great passions of her age—a compulsion to classify and a desire to improve by reform. What made Nightingale remarkable were the personal qualities of fierce intelligence and energy that enabled her to pursue these passions with the immense determination for which she was famed.