By Paul Theerman, Associate Director

How to get the word out? For the last two hundred years, health has been as much about education and prevention as intervention and response. And so an intrepid young doctor in the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) latched onto using the almanac as a public health vehicle. Health Almanac 1920 (Public Health Bulletin No. 98; Washington, GPO, 1920) was a 12-page almanac entwined in a 56-page public health pamphlet. Amid checking for the phases of the moon or the times of sunrise and sunset, one could find short pieces giving warning signs for cancer, means to prevent the spread of malaria, the necessity of registering births, and how to build a good latrine. These and many other topics were all presented by “Uncle Sam, M.D.”; the almanac was free for the asking.

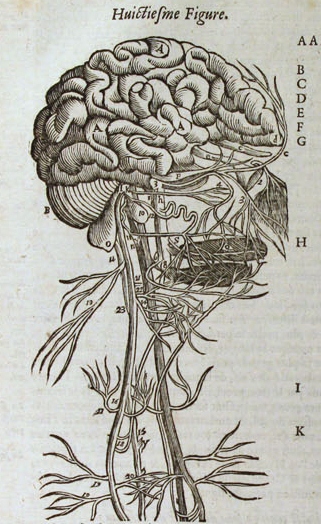

In the distant past, almanacs became linked to health through “astro-medicine” or “iatromathematics,” that is, medical astrology. Each of the signs of the zodiac was held to influence a system of the body, from Ares controlling the head to Pisces the feet, and so for everything in between. Almanacs were calendrical and astronomical, and in addition to marking sunrise and sunset, the phases of the moon, and religious holidays, they charted the day-by-day progress of the moon through the zodiac, with its supposed medical consequences. To this technical data, the most famous American almanac, Benjamin Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanac, added moralistic lessons and practical advice, wittily presented. Health Almanac 1920 provided these same features within the context of progressive secular government. The publication started with inspirational statements from President Woodrow Wilson, the Secretary of the Treasury, and the Surgeon General —who together formed the chain of command for the Public Health Service! Instead of a calendar of religious seasons and saints’ days, the almanac noted national days and significant events in the history of medicine and in “The Great War,” just concluded. Everywhere were health aphorisms: “Good health costs little, poor health costs fortunes” (from the back cover), and “Large fillings from little cavities grow” (April 20). Some “health hints” were quite flatly presented: “Every home should have a sewer connection or a sanitary privy” (July 20), and “Food, fingers, and flies spread typhoid fever” (July 31). Some were just to the point: “Be thrifty” (November 15) and “Wear sensible shoes” (December 18). Throughout, the almanac highlighted the role of the USPHS in promoting health.

The Health Almanac was published in 1919 and 1920—we have the 1920 edition—as was a parallel publication called the Miners’ Safety and Health Almanac, put out by the Bureau of Mines. Both were the brainchild of Dr. Ralph Chester Williams (1888–1984), then at the outset of his successful career with the Public Health Service. Born in Alabama and a 1910 graduate of the University of Alabama Medical School, Williams entered the USPHS in 1916 and was posted to the Bureau of Mines during World War I. Pulled into the Office of the Surgeon General, he edited Public Health Reports, served as Chief Medical Officer to the Farm Security Administration, as Medical Director of the USPHS’s New York City office, and starting in 1943, as Assistant Surgeon General and head of its Bureau of Medical Services. In that capacity he oversaw a third of the operations of the USPHS, including immigration inspection and USPHS hospitals. In 1951 the Commissioned Officers Association of the USPHS published his standard history, The United States Public Health Service, 1798–1950. At almost 900 pages, it dwarfs the Health Almanac 1920, but both show their author’s dedication to getting the word out about health and, not incidentally, about the agency that helped make that happen.