By Paul Theerman, Director

One hundred years ago, on December 21, 1922, Frederick Grant Banting (1891–1941) addressed the New York Academy of Medicine. He had been invited to give a talk on his new therapy that used insulin to treat diabetes. Less than a year earlier, in January 1922, the first diabetes sufferer had been successfully treated for this invariably fatal condition. Less than a year later, on December 10, 1923, Banting’s name was read out at the Nobel ceremony in Stockholm, as he and John Macleod were awarded the prize in Physiology or Medicine. During this Nobel month—the annual prizes were given out last Saturday, the 10th—we take a look at this signal discovery.

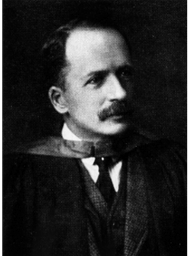

The story of the isolation and therapeutic use of insulin can be told as a remarkably short and direct one. After medical and surgical training at the University of Toronto and serving in World War I, Frederick Banting set up his medical practice in London, Ontario. He also taught there, at the University of Western Ontario, and as part of preparing for his lectures, he considered a possible solution to a persistent problem in diabetes studies. For over 50 years, medical researchers had explored the role of the pancreas gland in digestion, and specifically in diabetes. This condition is characterized by high levels of sugar in the urine, leading to frequent urination, increased thirst and hunger, and dramatic weight loss. The condition can progress to the acute symptoms of nausea, vomiting, and coma, eventually leading to death. There is no cure. In Banting’s time, sufferers faced a near-starvation diet as part of a difficult and short life.

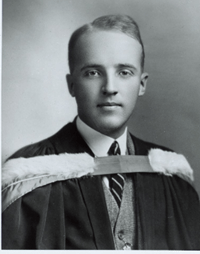

By the turn of the century, diabetes researchers had focused on the role in diabetes of the “islets of Langerhans,” microscopic glands spread throughout the pancreas. They supposed that a hormone produced by these glands—called “insulin” from the Latin word for “island,” given its source in the islets—played a crucial role in sugar metabolism. To use this insight therapeutically, though, ran up against a seemingly insurmountable challenge. One could hope to treat diabetes by administering an extract from the glands, and the usual way of preparing such extracts was to grind up the organ and then isolate and purify the hormone. But most of the pancreas produces digestive juices, and these juices promptly broke down the hormone. In 1920, Banting, reading through the medical literature, had a crucial insight: tying off the pancreatic duct could cause the rest of the pancreas to deteriorate, leaving behind only the insulin-producing islets. He took his idea to physiologist J. R. R. Macleod (1876–1935) at the University of Toronto, who provided him with a laboratory, experimental animals, and a medical student to help, Charles H. Best (1899–1978).

By April 2021, Banting and Best had begun work, tying off the pancreatic ducts in dogs, waiting for the pancreas to deteriorate, and then isolating the insulin from the remaining pancreatic tissue.

They soon turned instead to fetal calves as an insulin source—at an early stage of development, the islets of Langerhans already produced the hormone, while the pancreas’s digestive enzymes had not yet begun to be produced. In December Macleod assigned biochemist James Collip (1892–1965) to the project, to help purify the insulin and avoid allergic reactions.

After success in dogs, in January 1922 came the first successful therapeutic use in humans, at Toronto General Hospital, on 14-year-old Leonard Thompson. Then living on a 450-calorie-per-day diet and shrunk to 65 pounds, Thompson responded well to the insulin injections, and went on to live many more years. On February 7 Banting and Best announced their success at the Academy of Medicine of Toronto.

There was an immediate world-wide response. Patients flocked to Toronto for treatment. By 1923, the Eli Lilly Company was producing insulin commercially. In June 1923, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., contributed $150,000—equivalent to over $2.6M today—to 15 hospitals in the United States and Canada to support the use of insulin, including two New York hospitals, the Physiatric Institute and Presbyterian Hospital; two hospitals in Toronto; and $5,000 for the Banting-Best Fund of the University of Toronto. By December 1923, J. Sjöquist in his Nobel Presentation Speech could state: “Since [its discovery], the new remedy, the production of which does not offer any great technical difficulties, has come into use in practically all countries and with favourable results.”

Banting’s rewards were immediate and great. In 1922, he was given a Senior Demonstrator position at the University of Toronto, and the next year elected to the Banting and Best Chair of Medical Research at the University of Toronto. In August 1923 he made the cover of Time magazine. In December 1923 he and Macleod were awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology. Banting shared the credit and his prize money with Charles Best while Macleod did the same with James Collip. In 1925, the Banting Research Foundation was established, a private institution that supported his research, as well as that of other Canadian scientists. In 1934, he received a knighthood from King George V, and the following year was made a Fellow of the Royal Society.

In 1930, Banting was appointed the inaugural departmental chair of the Banting and Best Department of Medical Research. There he developed an interest in aviation medicine. With his help, Wilbur R. Franks (1901–1986), his Toronto colleague, developed an aviation “g-suit.” This garment used water-filled bladders to counteract the g-forces that developed during rapid acceleration that pulled blood away from the brain and caused blackouts. Banting was on his way to England to assist Franks in testing the suit for wartime use when his plane crashed in Newfoundland, near the town of Musgrave Harbour. He died February 21, 1941, at the age of 49. The New York Academy of Medicine had awarded Banting honorary Fellowship in 1933; at their May 1941 meeting, the Fellows honored his memory.

The story of insulin is, of course, more complex than this quick sketch affords. Historian Michael Bliss has looked more closely at Banting’s complicated life, and various authors have considered Banting’s long line of predecessors, the tensions among the Toronto team, and how credit was granted—or not—for isolating insulin. What is sure, though, is that this advance improved the lives of millions within a dramatically short span of time—a rare feat in the history of medicine.

Bibliography

Frederick G. Banting, “Facts; Biographical; Nobel Lecture,” The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1923, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1923/banting/facts/, accessed November 30, 2022.

F. G. Banting and C. H. Best, “The Internal Secretion of the Pancreas,” The Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine, 7 (5; February 1922): 256–71.

Michael Bliss, Banting: A Biography (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992).

Michael Bliss, The Discovery of Insulin (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982).

Alberto de Leiva, Eulàlia Brugués, and Alejandra de Leiva-Pérez, “El descubrimiento de la insulina: continúan las controversias después de noventa años/The discovery of insulin: Continued controversies after ninety years,” Endocrinología y Nutrición (English Edition) 58/9 (November 2011): 449–56. DOI: 10.1016/j.endoen.2011.10.001. https://www.elsevier.es/en-revista-endocrinologia-nutricion-english-edition–412-articulo-the-discovery-insulin-continued-controversies-S2173509311000614, accessed November 30, 2022.

“The Discovery and Early Development of Insulin,” The University of Toronto Libraries, March 2003, https://insulin.library.utoronto.ca/, accessed November 30, 2022.

Allison Piazza, “Shoot That Needle Straight (Item of the Month),” Books, Health, and History, November 18, 2016, https://nyamcenterforhistory.org/2016/11/18/shoot-that-needle-straight-item-of-the-month/, accessed November 30, 2022.

“Rockefeller Gives $150,000 for Insulin,” The New York Times, June 20, 1923.

James Ralph Scott, “In Memoriam, Frederick Grant Banting,” Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 17 (5; May 1941): 400–402.; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1933643/?page=1, accessed December 13, 2022.

J. Sjöquist, “Presentation Speech [on the occasion of the award of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine to Frederick Grant Banting and John James Richard Macleod],” December 10, 1923. The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1923, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1923/ceremony-speech/, accessed November 30, 2022.

Ignazio Vecchio, Cristina Tornali, Nicola Luigi Bragazzi, and Mariano Martini, “The Discovery of Insulin: An Important Milestone in the History of Medicine,” Frontiers in Endocrinology. 9 (23 October 2018): 613. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00613. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6205949/, accessed November 30, 2022.