Cara Kiernan Fallon, this post’s guest author, is a history of science PhD candidate at Harvard University.

“The seven ages of man.” From The Golden Health Library. Click to enlarge.

Childhood can be full of “vigor and zest” but “Middle age is the time when our sins against the laws of health find us out,” warned physicians writing for The Golden Health Library’s inaugural volume. Published in the late 1930s, The Golden Health Library offered readers five volumes of advice on the “principles of right living” so they could secure health throughout their lifespans.1 Authors included physicians, nurses, professors, and even birth control advocates like Margaret Sanger. September, Healthy Aging Month, is the perfect time to revisit this publication.

Part of the New York Academy of Medicine’s extensive collection of health guides, public health pamphlets, and medical magazines, The Golden Health Library highlights the growing health concerns associated with longer lives and an emerging notion of the elasticity of health in later life. Although originally published in the United Kingdom, people on both sides of the Atlantic expressed concerns over health into old age as they were living longer than ever before. Between 1901 and 1931, the population over age 65 nearly doubled from 1.8 to 3.5 million in the United Kingdom, and went from 3 million to 6.6 million in the United States.2 Life expectancy at birth, a figure largely affected by infant and childhood mortality, grew dramatically along with the expanding older population. With more people surviving childhood and living decades longer, a new wave of health concerns—and health advice—came with it.

“Healthy womanhood.” From The Golden Health Library. Click to enlarge.

“The wrestlers.” From The Golden Health Library. Click to enlarge.

In a section directly addressing health throughout the life course—“The Seven Ages of Man”—The Golden Health Library provided a series of articles on maintaining health in each of seven stages of life: infancy, childhood, adolescence, maturity, middle age, elderly age, and old age. Physicians identified “the elderly age” as a “very elastic” time between middle age and old age (87). Rather than following an arc of growth to decline, “The Seven Ages of Man” presented the elderly age as an expandable period of potential health, one determined by physical condition rather than a particular chronological period. Men who followed the rules of health and hygiene, and who had “lived wisely…may feel justified in expecting to live for the full period of life free from disease… and to die of old age” (88). Moderate diet, exercise, rest, and regular medical examinations would also ensure a “healthy elderly age for all women—the best antidote to old age” (91).

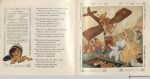

“On skis at 63.” From The Golden Health Library. Click to enlarge.

The idea of a healthy and elastic elderly age reflected important new concepts emerging in the 20th century. As people around the globe reached sixty, seventy, and eighty years of age in quantities never before seen, later life became a period of great diversity in physical, mental, social, and economic conditions. Readers were told that the “vigour and ability to do physical or mental work efficiently varies enormously in different people” but the “idea that advanced age in man must necessarily involve an arm-chair existence…is obsolete” (87, 89). Instead, it argued that “men are now never too old to lead an active life” (89). To demonstrate this new ideal, images of athleticism filled the pages of the elderly age. Fitness guru J. P. Muller was shown skiing in his undergarments at 63, and Lord Balfour was shown swinging for a tennis ball at the age of 80, both depicting the possibilities of health and vigor.

“Lord Balfour at eighty.” From The Golden Health Library. Click to enlarge.

Yet, the mid-century concept of a healthy elderly age also narrowly imagined health through a masculine body with physical freedom and strength. Despite women’s greater longevity—the article reminded readers that women lived on average five years longer than men at the time—the article offered no images of women living actively in the elderly age. Could no women be found to depict an ideal of healthy aging? Or did notions of health and age have different meanings for women than for men? Women may have been told they could achieve a healthy elderly age, but none could be found in these pages.

While the idea of healthy habits leading to a healthy older age offered a new optimism for the aging process, it also overlooked the powerful social and cultural influences on the biology, ability, and mobility of individuals. Recommendations throughout the lifespan for clean milk, sunny outdoor play, access to healthy foods, exercise, and regular physical exams reflected not merely physiological processes but more complex social and economic opportunities. Although the authors indicated that health throughout life was a matter of willpower, they acknowledged that few reached a disease-free old age. Were the ideals too lofty or were the challenges too great? Had their model failed to account for the complexities of health beyond a controllable regimen?

“A fine old age.” From The Golden Health Library. Click to enlarge.

“The Seven Ages of Man” offers an intriguing look into the early notions of healthy aging in the mid-20th century. While it responded to the growing population of older individuals, offering opportunities for self-determination and responsibility, it also reduced healthy aging to a matter of knowledge, willpower, and habit.

Decades later, efforts to improve the quality of life of older individuals continue to grow with the expanding population. Through its healthy aging initiatives and participation in Age-friendly NYC, the New York Academy of Medicine aims to address not only the physical components of aging but also issues of employment, housing, social inclusion, community health services, and many other social, psychological, and economic concerns for seniors. Looking back to The Golden Health Library allows us to explore the formative stages of important themes today – the growing belief in the elasticity of later life, the new emphasis on “healthy” and “active” aging, and the changing understandings of the powerful social and cultural influences on biology.

References

1. Browning, E., Stanford Read, C., Williams, L. L.B., Crawford, B. G. R., Arbuthnot Lane, W., Somerville, G. (193?). The seven ages of man. In W. Arbuthnot Lane (Ed.), The golden health library (pp. 48–96). London: William Collins Sons & Co. All parenthetical page numbers refer to this publication.

2. For the United Kingdom, see the Office for National Vital Statistics, Chapter 15 Population: Age distribution of the resident population, 15.3(a). For the United States, see the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Vital Statistics System, Population by Age 1900 to 2002, No. HS-3.

March 26 marks the birthday of the man behind one of my favorite books in our collection.

March 26 marks the birthday of the man behind one of my favorite books in our collection.