Today we have a guest post written by Monica Green, a longtime NYAM researcher.

Several times over the past 30 years, I’ve consulted a mid-13th-century manuscript in the New York Academy of Medicine’s holdings. This large, 94-leaf, handsomely bound volume was formative to my training as a historian of medieval medical history, having been the first “real” manuscript I examined when I was beginning my researches on the so-called Trotula texts in the early 1980s.

Opening of Caelius, f. 61ra

Like most scholars who study the history of intellectual traditions, my eyes were on my immediate object of study—in this case, a 12th-century compendium of texts on women’s medicine and cosmetics. My peripheral vision went no further than the other texts on women’s medicine that surrounded it in the manuscript. These were certainly enthralling: they included one of only two known copies of the Gynecology of the 4th-century writer, Caelius Aurelianus. But the other contents of the manuscript, let alone its structure as a whole, were all but invisible to me.

I did come back, many years later, with some questions about one of the surgical texts in the volume. This was the visually stunning (and rightly famous) Surgery of the early 11th-century Cordoban physician, Abu al-Qasim Khalaf ibn ‘Abbas al-Zahrawi, whose work had been translated from Arabic into Latin in Toledo. But the NYAM manuscript was not a unique copy (al-Zahrawi’s work exists in some 33 extant Latin manuscripts), and so—my questions quickly answered—I moved on again.

But my attention was brought back to the NYAM volume again last year, because of some questions being raised by a new project. Two problems seemed to revolve around each other: why was there a 50-year gap between when the Arabic-into-Latin translator Gerard of Cremona died in 1187 (he was the one who had translated al-Zahrawi) and when his texts first started to be regularly used and cited? And, secondly, why did so many copies of these works, once they did appear, seem (a) to cluster around Paris and (b) show a level of magnificence in decoration that most medical texts had never previously enjoyed?

Suddenly, the NYAM manuscript took on new significance: the illumination and decoration, which I had previously ignored, became newly important. And so, too, did the “minor” texts, such as the Surgery of Horses, of which this is likewise an early copy. This really was a most unusual manuscript, I realized. And the physical character of the book—its structure and decoration as well as its contents—were key to figuring it out. So here I am this summer, back to consult it again.

f. 77ra, opening of Trotula

The gynecological unit, which I had worked with most extensively, was the most typical: the Trotula text, for example, opens with a lovely “puzzle” initial ‘U’, but there is nothing here to distinguish the manuscript from many hundreds of others made in the same period.

Not so for the surgical section of the manuscript. First was the cautery section: most of what must have been about two dozen images had been cut away (yes, they had art thieves already in the Middle Ages!). But the two images that remain show, in quite typical northern European style, images of a surgeon applying hot burning irons to the surface of the patient’s body in order to heal, respectively, sciatica and heart or stomach problems.

f. 3ra, cautery scenes

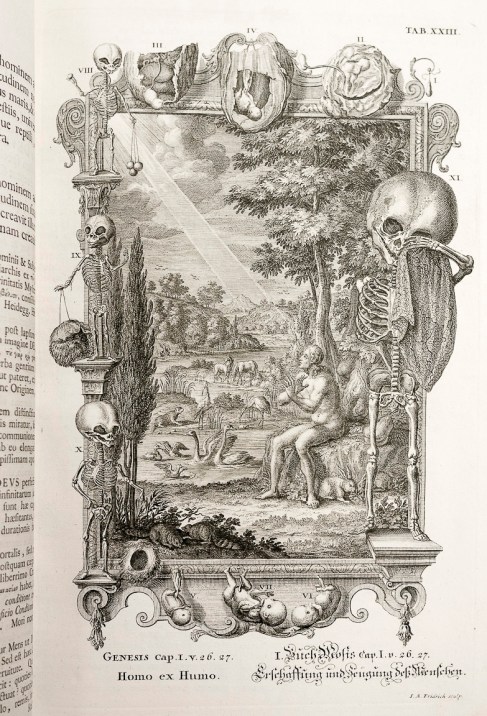

f. 45ra, opening of Roger, Chirurgia

Immediately following was a sequence of other surgical texts. Each one of them had a striking opening initial, framed in gold leaf with elegant foliated designs that are very similar to the output of an artist’s workshop in Paris associated with the name of the Johannes Grusch. The three-headed devil that opens the Surgery of Roger Frugardi is especially memorable.

f. 23va: sample champie initial and clapsedra

But in the middle of that sequence of smaller surgical texts (all of which probably came out of southern Italy) comes the al-Zahrawi text, with its own unique decoration scheme. Here we find throughout the text elegant gold-leaf initials, drawn against alternating light blue or rose-colored backgrounds with white ink filigree. (Art historians call this a “champie” decoration.) And, of course, here we find the depictions of surgical tools that characterize all the copies of al-Zahrawi’s surgical text, whether Latin or Arabic. The different decoration schemes seemed to correspond to different places from where the commissioner of this book was getting his exemplars (the manuscripts from which this manuscript was copied).

So in what sense does being in a digital age give us “new eyes”? I had the physical manuscript right in front of me: 800 years of history that I could touch with my hands. Nothing “virtual” about this! Ah, but the New York Academy of Medicine was not this book’s original home. Because so many European libraries are now making their manuscripts available digitally online, it is possible to reconstruct virtually what medieval libraries looked like, to reassemble their components and reconstruct how they came into being. Because I could learn more about other manuscripts produced at the same time, I was now beginning to understand how extraordinary this manuscript’s medieval home had been.

The NYAM manuscript was commissioned in the mid-13th century by Richard de Fournival, a surgeon and, eventually, the chancellor of the cathedral of Amiens. (de Fournival had gotten special dispensation from the Pope to continue his surgical practice despite his being a cleric. His father and nephew were physicians, too.) The NYAM manuscript captures all the international networks that de Fournival belonged to: English, Norman, French, and Italian. Besides being a cleric and a surgeon (and a poet and musician), de Fournival was a librarian—not simply a collector but a curator of books. The library he created of 162 volumes (comprising many 100s of different texts) literally changed the course of history in laying the foundation for a new, more sophisticated medical system in Europe that was as influential in establishing the social worlds of physicians and other medical practitioners as it was in defining their intellectual worlds. It was de Fournival, I was realizing, that was instrumental in rediscovering Gerard of Cremona’s translations (including al-Zahrawi’s Surgery) and introducing them into the fertile context of the Parisian academic world.

In our day, Google and PubMed and any number of Internet resources make us lose sight of where knowledge comes from. Everything seems freely available, whenever we want it. But books were once extraordinarily precious. Juxtaposing the digital with the real vellum and leather and wood and gold leaf of a medieval manuscript is an excellent reminder of the cultures of learning we still share across the centuries.

Monica H. Green is a specialist in medieval medical history and the global history of health. She would like to thank Alison Stones for the impetus to bring “new eyes” to the NYAM manuscript, and Jocelyn Wogan-Browne for making this New York sojourn possible. And, of course, the NYAM librarians for once again making the manuscript available for study. Green will be spending the 2013-14 academic year at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. She can be reached at monica.green@asu.edu.