By Sonia Shah

Sonia Shah, today’s guest blogger, is a science journalist and author of Pandemic: Tracking Contagions from Cholera to Ebola, and Beyond (Sarah Crichton Books/Farrar, Straus & Giroux, February 2016), from which this piece, including illustrations, is adapted.

On February 23 at 6pm, Shah will moderate the panel “Where Will the Next Pandemic Come From?,” cosponsored by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. Register to attend.

Over the past 50 years, more than 300 infectious diseases have either newly emerged or re-emerged into territory where they’ve never been seen before. The Zika virus, a once-obscure pathogen from the forests of Uganda now rampaging across the Americas, is just the latest example. It joins a legion of other diseases that have similarly broken out of earlier constraints, including Ebola in West Africa, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in the Middle East, and novel avian influenzas in Asia, one of which hit the U.S poultry industry last spring, causing the biggest animal disease epidemic in U.S history.

When such pathogens spread like a wave across continents and global populations, they cause pandemics, from the Greek pan (“all”) and demos (“people”). Given the number of pathogens in our midst with pandemic-causing biological capacities, pandemics themselves are relatively rare. In modern history, only a few pathogens have been able to cause them: Yersinia pestis, which causes bubonic plague; variola, which causes smallpox; influenza A; HIV; and cholera.

Cholera is one of the history’s most successful pandemic-causing pathogens. The first cholera pandemic began in the Sundarbans in present-day Bangladesh in 1817. Since then, it has ravaged the planet in no fewer than seven pandemics, the latest of which is currently smoldering just a few hundred miles off the coast of Florida, in Haiti.

Cholera first perfected the art of pandemics by exploiting the rapid changes in transportation, trade, and demography unleashed by the dawn of the factory age. New, fast-moving transatlantic clipper ships and sailing packets, which moved millions of Europeans into North America, brought cholera to the New World in 1832. Thanks to the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, the bacterial pathogen easily spread throughout the country, including into the canal’s southern terminus, New York City, which suffered repeated cholera epidemics over the course of decades.

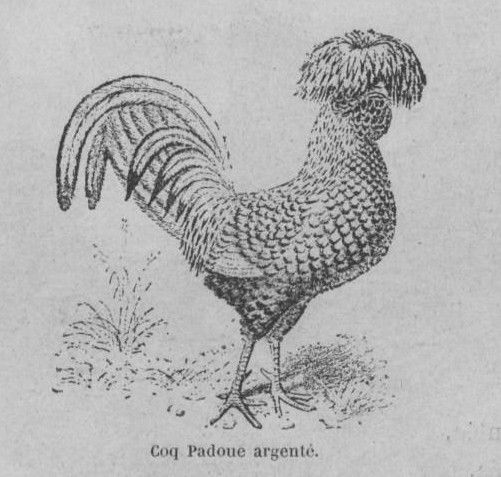

The spread of cholera after the opening of the Erie Canal.

Cholera was well-poised to exploit the filth of 19th-century cities. The pathogen spreads through contaminated human waste. And outhouses, privies, and cesspools covered about 1/12 of New York City, none of which were serviced by sewer systems and few of which were ever emptied. (Those that were had their untreated contents unceremoniously dumped into the Hudson or East Rivers.) The contents of countless privies and cesspools spilled out into the streets, leaked into the city’s shallow street-corner wells, and trickled into the groundwater.

Even those who enjoyed piped water were vulnerable to the contagion. The company chartered by New York State to deliver drinking water to the city’s residents—the Manhattan Company, which started a bank now known as JPMorgan Chase—dug their well among the tenements of the notoriously crowded Five Points slum, in what is today part of Chinatown. They delivered the slum’s undoubtedly contaminated groundwater to one third of the city’s residents.

The 1832 cholera outbreak in New York City. The Manhattan Company, now JP Morgan Chase, sank its well amidst the privies and cesspools of the Five Points slum, atop the site of the Collection Pond, which had been filled in with garbage. The water was distributed to 1/3 of the city of New York.

Just as the Zika and MERS viruses confound modern-day medicine, so too did cholera confound 19th-century medicine. Under the 2,000-year-old spell of miasmatism—the medical theory that diseases spread through stinky airs, or miasmas—doctors couldn’t bring themselves to admit that cholera spread through water, despite convincing contemporary evidence that it did.

But that doesn’t mean there was nothing that could have been done to mitigate the cholera pandemics of the 19th century.

The Manhattan Company knew the water they distributed was dirty. As a former director of the company admitted in 1810, Manhattan Company water was rich with its users’ “own evacuations, as well as that of their Horses, Cows, Dogs, Cats, and other putrid liquids so plentifully dispensed.” New Yorkers decried its smell and taste, which they variously derided as “abominable” and “nauseating.”1 They suspected, too, that the company’s water made them sick. “I have no doubt,” one letter writer opined to a local paper in 1830, “that one cause of the numerous stomach affections so common in this city is the impure, I may say poisonous nature of the pernicious Manhattan water which thousands of us daily and constantly use.”2

And New York’s physicians knew that cholera was coming down the Erie Canal and the Hudson River, heading straight for the city. Dr Lewis Beck, who collected the data mapped above admitted that the pattern of disease did “favor the idea that cholera is contagious,”3 and travelling down the waterways into New York City. So many people feared the migrants coming down the waterways during cholera outbreaks that residents of towns lining the canal refused to let passengers on passing boats disembark. In 1893, in fear of a cholera outbreak, an armed mob surrounded the cholera-infected passengers of the Normannia, a vessel recently arrived from Hamburg, Germany, trapping hundreds aboard for days.

But despite the public’s fears of contagion and contaminated water, little was done to protect the city from either. The city’s leadership refused to enact quarantines along the canal or the Hudson for fear of disrupting the lucrative shipping trade that had transformed New York from a backwater to the Empire State. The Manhattan Company retained its charter, despite public outcry about the quality of their water. The political machinations of the infamous Aaron Burr, pursuing his murderous rivalry with the now-storied founding father Alexander Hamilton, assured that.

Instead, each wave of deadly contagion was met with minor adjustments to society’s defenses against pathogens. International conferences began in 1851 to organize cross-border quarantines against cholera and other diseases. New York City opened its first independent health department, staffed by physicians rather than political appointees, in 1865, as cholera loomed (thanks in large part to the efforts of the New York Academy of Medicine). These reactive, incremental measures couldn’t stave off nearly a century of deadly cholera pandemics, but as the decades passed, they formed the foundation for the global health system we enjoy today. Following New York City’s example, independent health departments were built across the country. The international conferences to tame cholera led to the formation of the World Health Organization, in 1946.

Today, we continue to fight contagions in a similarly reactive, incremental fashion. After Ebola infected tens of thousands in West Africa and elsewhere, hospitals in the United States and other countries beefed up their investments in infection control. After mosquito-borne Zika infected millions across the Americas, public health agencies focused anew on the problem of disease-carrying insects.

Whether these measures will be sufficient to defuse the next pandemic remains to be seen. But a more comprehensive, proactive approach to defanging pandemics is now possible, too. The history of pandemics reveals the role of human activity in the emergence and spread of new pathogens. Industrial developments that disrupt wildlife habitat; rapid, ad hoc urbanization; intensive livestock farming; sanitary crises; and accelerated trade and travel all play a critical role, just as they did in cholera’s heyday. In some places, we can diminish the pathogenic threat these activities pose. In others, we can step up surveillance for new pathogens, using new microbial sleuthing techniques. And when we find the next pandemic-worthy pathogen, we can work to contain it—before it starts to spread.

References

1. Pandemic, p 64. From Koeppel, Gerard T. Water for Gotham: A history. Princeton University Press, 2001, 121, 141.

2. Pandemic, p 63. from Blake, Nelson Manfred. Water for the cities: A history of the urban water supply problem in the United States. No. 3. Syracuse University Press, 1995, 126.

3. Pandemic, p 106. from Tuite, Ashleigh R., Christina H. Chan, and David N. Fisman. “Cholera, canals, and contagion: Rediscovering Dr Beck’s report.” Journal of public health policy 32.3 (2011): 320-333.

![[Rappresentazione zodiacale in tre quadri consecutivi]. Image ID: 425361. Courtesy of the New York Public Library](https://nyamcenterforhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/nyplcolor16gk-page-012.jpg?w=584&h=779)