By Becky Filner, Head of Cataloging

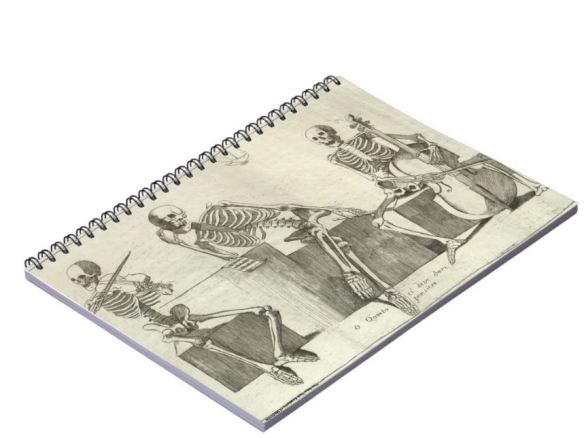

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, medical schools offered academic prizes, frequently accompanied by a monetary award, for the best essays, examinations, and student notebooks.[1] The New York Academy of Medicine’s Library holds several examples of prize-winning student medical notebooks, including John E. Stillwell’s Report of Prof. Thomas’ Gynecological Clinics, Session of ’73 and ’74. This notebook is an ornate presentation copy, not the rough notes Stillwell would have taken during the clinics. Written in a neat, legible hand, it also includes a calligraphic title page and twenty-nine watercolor illustrations. The notebook is bound in full leather with blind-stamped fleurs-de-lis and shamrocks on the cover and spine. The notes are from a series of clinics offered during the 1873-1874 school year by Theodore Gaillard Thomas, a professor of gynecology at New York’s College of Physicians and Surgeons and author of A Practical Treatise on the Diseases of Women.

Calligraphic title page of John E. Stillwell’s Report of Prof. Thomas’ Gynecological Clinics: autograph manuscript, 1873-1874.

Stillwell’s notes, like Thomas’s lectures, are organized into a series of case studies. In the case study shown below, a woman named Annie Coyle reports that “her friends noticed her abdomen increasing in size” and her “menses … are ‘larger’ and … come twice as often as they ought.” When she had an examination at the dispensary, the examiner “pronounced her pregnant”; she came to Dr. Thomas for an examination because she was “unwilling to rest under such unjust suspicions.”

Stillwell’s carefully transcribed lecture notes and a watercolor showing a woman with an ovarian tumor, from Stillwell’s autograph manuscript, Report of Prof. Thomas’ Gynecological Clinics, 1873-1874.

Dr. Thomas notes that he found an abdominal tumor and gives details on how he determined that it is a “fluid tumor” rather than one “that is filled with air or that is solid.” He rules out pregnancy because he cannot feel any movement when he places his hands on her abdomen and her mammary glands are not enlarged. His conclusion is that she has an ovarian cyst and requires an ovariotomy to remove it. Stillwell’s account of the clinic is accompanied by a watercolor of a female figure with an enlarged abdomen labeled, “Ovarian Tumor.” Other clinics in the notebook cover problems of the uterus and cervix, tumors, peritonitis, fibroids, complications during and after pregnancy, menopause, dementia, and sterility. There is even an account (with an illustration) of a woman who has two vaginas.

Watercolor by John E. Stillwell of a retroflexed uterus, from his Report of Prof. Thomas’ Gynecological Clinics, 1873-1874.

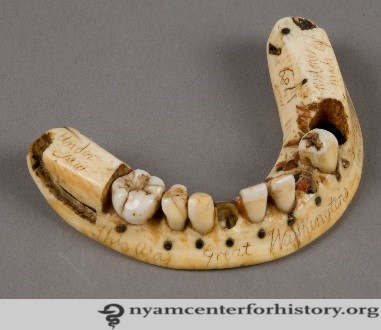

Student medical notebooks were usually submitted anonymously to ensure that the judging would not be biased. In this case, we know that Stillwell submitted this prize-winning notebook (even though the notebook does not contain his name) because the Library acquired the notebook along with the prize itself, a wooden case of gynecological instruments with a plaque that reads, “A Prize Awarded for the best Gynecological Report of 1874 in the College of Physicians and Surgeons N.Y. by Prof. T. Gaillard Thomas to J.E. Stillwell.”[2]

A plaque on the wooden case indicates that Stillwell received this prize from Prof. Thomas for the “best Gynecological Report of 1874 in the College of Physicians and Surgeons.”

Stillwell’s prize consisted of a full set of gynecological instruments stored in a sturdy wooden box lined with purple velvet. The instruments were made by G. Tiemann & Co., Manufacturers of Surgical Instruments, 67 Chatham St., N.Y.

The tools include all the necessary implements for a gynecology practice in the 1870s. Thomas describes many of the tools in his A Practical Treatise on the Diseases of Women (which was a required textbooks for medical students at the College of Physicians and Surgeons around this time). Shown below are drawings of several of the tools, including “Buttles’ spear-pointed scarificator,” a “hard rubber cylinder for dry-cupping the cervix uteri,” cauterizing irons, and tools for sutures, and descriptions of how they were used.[3]

Taken from T. Gaillard Thomas’s A Practical Treatise on the Diseases of Women, 2nd ed., these drawings show obstetrical tools and give brief descriptions of how they were used.

Taken together, John E. Stillwell’s prize notebook and the handsome case of obstetrical tools that he won for his efforts provide an interesting window into both 19th-century medical school competitions and 19th-century obstetrics and gynecology.

References

[1] Contemporary handbooks from medical schools list the types of prizes awarded and the prize money attached to them. See, for example, the section on “Prizes” under “School of Medicine” in Columbia College’s Handbook of Information as to the Several Schools and Courses of Instruction 1886-1887, p. 222-225.

[2] An account of the commencement exercises of the College of Physicians and Surgeons in The Medical Record confirms Stillwell’s receipt of the Thomas prize. “The Thomas prize was awarded to J.E. Stillwell, for a report on ‘Cliniques for Diseases of Women’” (The Medical Record, ed. George F. Shrady, New York: W.M. Wood & Co., v. 9, issue of March 16, 1874, p. 158).

[3] Thomas, Theodore Gaillard. A Practical Treatise on the Diseases of Women, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: Henry C. Lea, 1869).

“On October 26th, the Academy Library convened ‘Archives, Advocacy and Change: Tales from Four New York City Collections.’ I moderated a lively conversation with all-star panelists Jenna Freedman (Barnard College), Steven Fullwood (In the Life Archive), Timothy Johnson (Tamiment Library, New York University) and Rich Wandel (The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center). The discussion hit on a lot of fascinating issues, including how archivists shape the historical record with the selection and acquisition choices they make, issues of privilege, and access for communities.”

“On October 26th, the Academy Library convened ‘Archives, Advocacy and Change: Tales from Four New York City Collections.’ I moderated a lively conversation with all-star panelists Jenna Freedman (Barnard College), Steven Fullwood (In the Life Archive), Timothy Johnson (Tamiment Library, New York University) and Rich Wandel (The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center). The discussion hit on a lot of fascinating issues, including how archivists shape the historical record with the selection and acquisition choices they make, issues of privilege, and access for communities.”  “I was excited to learn in 2016 that the Library holds

“I was excited to learn in 2016 that the Library holds  “Most of my works has a lot to do with satisfaction—satisfactions from cleaning dusted books, from placing crumbled health pamphlets into clean, acid-free envelopes, from making fitted enclosures for damaged books, from putting torn pieces together, and so much more. But all of these satisfactions is ultimately coming from that I’m contributing in preservation of the library materials to be more accessible and usable for the future! One of the most memorable item I worked through in

“Most of my works has a lot to do with satisfaction—satisfactions from cleaning dusted books, from placing crumbled health pamphlets into clean, acid-free envelopes, from making fitted enclosures for damaged books, from putting torn pieces together, and so much more. But all of these satisfactions is ultimately coming from that I’m contributing in preservation of the library materials to be more accessible and usable for the future! One of the most memorable item I worked through in  “A recent highlight for me would be our first

“A recent highlight for me would be our first

“Dr. Paul Schneiderman brought his Columbia dermatology residents to visit the rare book room on August 26th so that we could explore the history of dermatology. Looking at highlights from the dermatology collection from the 16th through the 20th centuries gave the residents a chance to think about the many ways in which their specialty has changed over time, especially since dermatology relies so heavily on visual representation. We looked at hand colored engravings, chromolithographs, photographs and stereoscopic images and the residents and their mentor engaged in lively debates about whether the descriptions and images matched with current information about some of the diseases that were shown. Not only did the residents have the opportunity to see these wonderful materials, but I had the pleasure of learning more about how to interpret the images from them.” –Arlene Shaner, Historical Collections Librarian

“Dr. Paul Schneiderman brought his Columbia dermatology residents to visit the rare book room on August 26th so that we could explore the history of dermatology. Looking at highlights from the dermatology collection from the 16th through the 20th centuries gave the residents a chance to think about the many ways in which their specialty has changed over time, especially since dermatology relies so heavily on visual representation. We looked at hand colored engravings, chromolithographs, photographs and stereoscopic images and the residents and their mentor engaged in lively debates about whether the descriptions and images matched with current information about some of the diseases that were shown. Not only did the residents have the opportunity to see these wonderful materials, but I had the pleasure of learning more about how to interpret the images from them.” –Arlene Shaner, Historical Collections Librarian What follows is an engaging, often-times laugh-out-loud narrative of Dick’s new life with diabetes. Accompanying each chapter are charming illustrations by W. Joseph Carr.

What follows is an engaging, often-times laugh-out-loud narrative of Dick’s new life with diabetes. Accompanying each chapter are charming illustrations by W. Joseph Carr. In another chapter, Dick agrees to be a diabetes research participant at a lab. In a passage that would make any 21st century Institutional Review Board member cringe, the doctor explains to Dick what it means to be a “guinea-pig”:

In another chapter, Dick agrees to be a diabetes research participant at a lab. In a passage that would make any 21st century Institutional Review Board member cringe, the doctor explains to Dick what it means to be a “guinea-pig”: Another highlight of the book is Dick’s (somewhat inexplicable) trip to Munich, Germany with his mother during Adolf Hitler’s reign. During the trip, Dick is hospitalized with painful sores. The situation is, understandably, quiet stressful for Dick, but he takes it in stride:

Another highlight of the book is Dick’s (somewhat inexplicable) trip to Munich, Germany with his mother during Adolf Hitler’s reign. During the trip, Dick is hospitalized with painful sores. The situation is, understandably, quiet stressful for Dick, but he takes it in stride: