By Lisa O’Sullivan, Director, Center for the History of Medicine and Public Health

The August item of the month is Ambroise Paré’s (1510 –1590) Les Oeuvres, or Works. Published in 1575 in 26 sections or books, the folio volume has 295 illustrations and includes Paré’s writings on anatomy, surgery, obstetrics, instrumentation, and monsters. This post focuses on Paré’s military surgery and is the first in a series of occasional posts looking at the relationship between medicine and war.

Frontispiece of the first (1575) edition of Les Oeuvres, dedicated to King Henri III. Click to enlarge.

Dedicated to Henri III, Paré presents Les Oeuvres as an accumulation of his life’s studies and experience, and it incorporates many of his earlier publications. The French barber surgeon spent much of his life at war, serving in over 40 campaigns, and published numerous highly influential books, many of them directly based on his practice of military surgery.i Paré’s career was a prestigious one, progressing from working as an apprentice barber surgeon to great prominence as surgeon to Henry II, and subsequently his successors Francois II, King Charles IX, and Henry III.

Like his contemporary Andreas Vesalius, Paré is now celebrated as an emblematic figure of Renaissance thinking, willing to look beyond the established authorities and instead rely on the evidence of his own experience. In the Oeuvres, for instance, he mocks the use of “mummy” or “mummia,” a popular remedy ostensibly created from Egyptian mummies and used extensively by physicians.ii Such a position was particularly provocative given Paré’s identity as a surgeon, rather than a university trained physician with a formal education and knowledge of Greek and Latin.

Despite Paré’s close connections with many of its members, the Parisian Faculty of Medicine attempted to block the publication of the Oeuvres, arguing that the Faculty needed to approve all publications relating to medicine and surgery. In addition, they objected to Paré’s use of French, as he was among a small but increasing number of practitioners writing in the vernacular rather than the more scholarly Latin, making such works vastly more accessible to students of surgery operating outside the universities and the lay public.iii

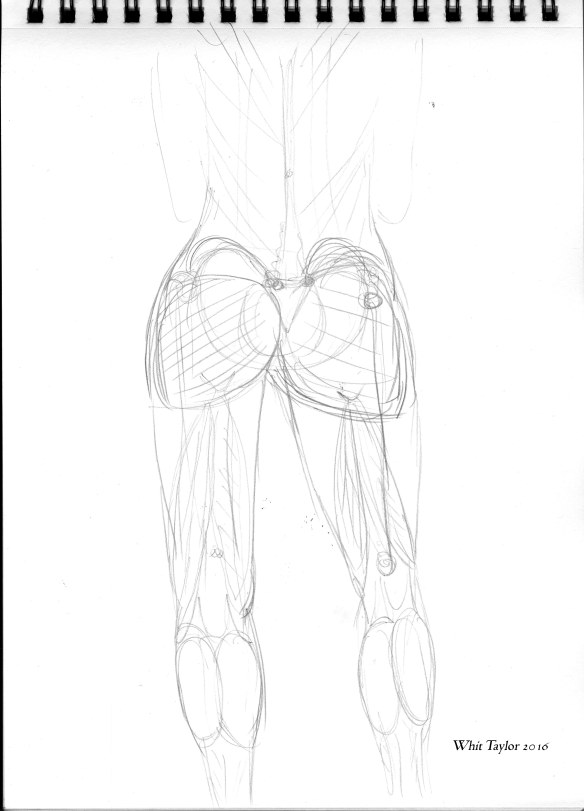

Reminiscent of a “wound man,” this illustration demonstrates techniques for extracting broken arrows from the body. Click to enlarge.

Much of Paré’s renown was based on his early work in the military context. Throughout the Oeuvres, he returns to examples of treating soldiers wounded during conflict. Perhaps the most famous vignette describes how, during his first campaign in 1536, Paré found that he had insufficient boiling oil to use in cauterizing gunshot wounds, and instead used a liniment made of egg yolk, rose oil, and turpentine. The following day, he discovered that those soldiers treated with the liniment were in a better condition than those whose wounds had been treated according to the prescribed manner. He subsequently argued for the treatment of gunshot wounds with liniments and bandaging, as well as removing affected tissue from the wound.iv

Gunpowder, whether projected from cannons or shot from firearms, had become a significant factor on European battlefields in the late 14th century. The use of gunpowder dramatically changed the practice of warfare. Increasingly numerous and accurate firearms contributed to the number of soldiers killed and wounded. These weapons produced new types of wounds that penetrated into the body, carrying foreign materials with them and leading to gangrene, while also deafening and blinding those near blasts.v

A variety of tools for extracting bullets from wounds. On the top left, “crane bill” forceps for fragmented bullets; on right a shorter “duck bill” instrument designed for extracting whole bullets. At bottom, “lizard noses” for drawing out flattened bullets. Click to enlarge.

Surgeons based their treatment of gunshot wounds on the belief that the gunpowder carried into the body by the bullets brought poison with it. This idea came from Giovanni da Vigo (1450–1525), an Italian surgeon whose 1514 Practica in arte chirurgica copiosa and 1517 Pratica in professione chirurgica were highly influential surgical texts. Rapidly translated into multiple European languages, these books include da Vigo’s suggestion to cauterize (burn) the wound with boiling oil in order to counteract the poisonous traces of gunpowder and to seal any severed arteries. This procedure became considered standard practice.viParé, after his experience with liniment rather than oil, experimented further, and recounts seeking advice from other surgeons and testing a folk remedy for onion poultices for burns suggested by an older local woman. Concluding that they were effective against blistering offered Paré another rhetorical opportunity to emphasize his commitment to observation and experimentation.vii

The evidence found in earlier surgical manuals suggests that medieval surgeons had made similar experiments, and that it was the popularity of the more recent ideas promulgated by da Vigo that led to treatments with cauterization and oil.viii While he was not the only surgeon to be working towards more humane and effective treatment of gunshot wounds, Paré became the most well-known and is often celebrated today as the “father” of modern military surgery.ix This reputation rests on not only his work around gunshot wounds but his broad interests, influence, and innovation. A future post will explore other aspects of Paré’s Oeuvres and its long-term impact on military surgery.

References

i. A full bibliography of his works was produced by Academy librarian Janet Doe in 1937. See Janet Doe, A Bibliography of the Works of Ambroise Pare; Premier Chirurgien et Conseiller du Roy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1937).

ii. Ambroise Paré, Les Oeuvres de m. Ambroise Paré … Avec les figures & portraicts tant de l’anatomie que des instruments de chirurgie, & de plusieurs monstres. Le tout diuisé en vingt six livres … (Paris : Chez G. Buon, 1575), p399.

iii. Paré defended his publication with a written defense and in the Parisian courts. While the verdict was not recorded, the book went on sale and sold out almost immediately. See Wallace B Hamby, Ambroise Paré, Surgeon of the Renaissance (St. Louis: W.H. Green, 1967), pp153-156.

iv. Ambroise Paré, Les Oeuvres de m. Ambroise Paré, pp357-359.

v. John Pearn, “Gunpowder, the Prince of Wales’s Feathers and the Origins of Modern Military Surgery,” ANZ Journal of Surgery 82 (2012): 240–244, 241; Kelly R DeVries, “Military Surgical Practice and the Advent of Gunpowder Weaponry,” The Canadian Bulletin of Medical History / Bulletin canadien d’histoire de la médecine 7(2) (1990):131-46, p135.

vi. DeVries, “Military Surgical Practice and the Advent of Gunpowder Weaponry,” pp141-142.

vii. Ambroise Paré, Les Oeuvres de m. Ambroise Paré, p359.

viii. DeVries, “Military Surgical Practice and the Advent of Gunpowder Weaponry,” p142.

ix. Frank Tallett, War in Context: War and Society in Early Modern Europe : 1495-1715 (London, US: Routledge, 2010), pp108-110.