By Becky Filner, Head of Cataloging

World Breastfeeding Week – August 1-7, 2016 – seeks to promote, protect, and support breastfeeding. How was breastfeeding regarded in the past? To answer this question, I consulted books on child rearing from the early 19th century to the mid-20th century.

The earliest book I looked at, Dr. William Buchan’s 1804 Advice to Mothers, on the Subject of Their Own Health; and on the Means of Promoting the Health, Strength, and Beauty, of Their Offspring, is extremely critical of women who do not breastfeed:

Unless the milk….finds the proper vent, it will not only distend and inflame the breasts, but excite a great degree of fever in the whole system… It may be said, that there are instances without number, of mothers who enjoy perfect health, though they never suckled their children. I positively deny the assertion; and maintain, on the contrary, that a mother, who is not prevented by any particular weakness or disease from discharging that duty, cannot neglect it without material injury to her constitution.1

At the end of the 19th century, Dr. Genevieve Tucker’s Mother, Baby, and Nursery: A Manual for Mothers (1896) also strongly advocates breastfeeding:

Every mother who has health sufficient to mature a living child ought, if possible, to nurse it from her own breast. Her own health requires it, as the efforts of the child to draw the milk causes the uterus to contract, and nothing else will take its place to her infant.2

Much of her other advice seems outdated now, including her claim that “nursing babies suffer from too frequent nursing” and her suggestion to nurse “as seldom as possible at night.” Perhaps strangest to modern ears is her analysis of a woman’s ability to nurse based on her physical and emotional state:

Different temperaments and constitutions in women have great influence in the quantity and quality of milk. The richest milk is secreted by brunettes with well developed muscles, fresh complexions, and moderate plumpness. Nervous, lymphatic, and fair-complexioned women, with light or auburn hair, flabby muscles, and sluggish movements, as a rule, secrete poor milk. Rheumatic women secrete acid milk, which causes colic, diarrhea, and marasmus in the child.3

Tucker also suggests that a nursing mother should be producing a whopping forty-four ounces of breast milk every twenty-four hours.

Dr. Charles Gilmore Kerley in his Short Talks with Young Mothers: On the Management of Infants and Young Children wrote in the early 19th century that contemporary pressures on women hinder their breastfeeding abilities:

A mother, to nurse her child successfully, must be a happy, contented woman… The American women of our large cities assume the cares and responsibilities of life equally with men. Among the so-called higher classes, — those who have all that wealth and position can give, — there is a constant struggle for social pre-eminence. Among the majority of the so-called middle classes the contest for wealth and place never ceases from the moment the school days begin until death or infirmity closes the scene. Among the poor there are the ceaseless toil, the struggle for food and shelter, the care of the sick, and the frequent deaths of little ones in the family whom they are unable properly to care for. In all classes, therefore, the conditions of life are such as seriously to interfere with the normal function of nursing, no matter how excellent may be the mother’s physical condition.4

This emphasis on a woman’s mind being at rest is repeated in much of the early 20th- century literature on breastfeeding.

Most of the books from the first few decades of the 20th century contain a passage about keeping the breasts and nipples clean. Kerley and others recommend washing the nipples (and even the child’s mouth!) with a solution of boracic (boric) acid. Myrtle M. Eldred and Helen Cowles Le Cron write in For the Young Mother (1921) that “the breasts are tender and easily infected at first, so that the boric acid acts as a cleanser to protect the baby from possible germs and as a preventive of abscessed breasts.5”Boric acid, though it is sometimes used as an antiseptic, is toxic to humans if taken internally or inhaled in large quantities. Other books recommend rinsing the breasts with hot water prior to nursing.6

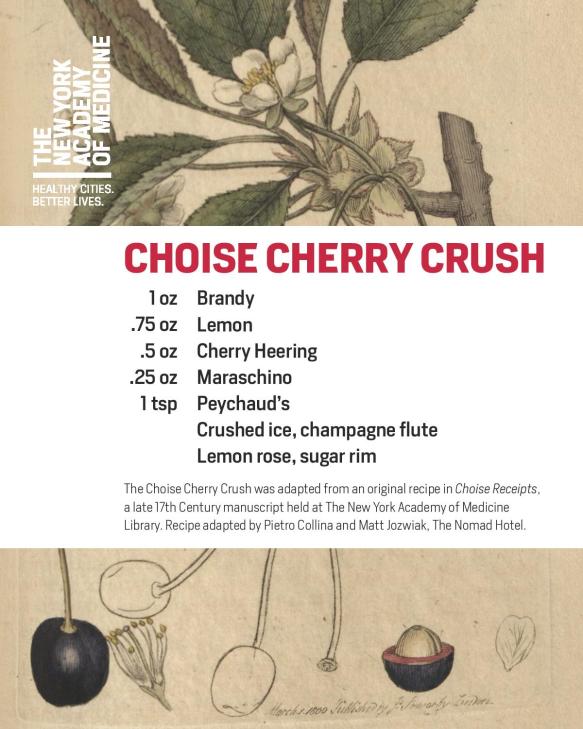

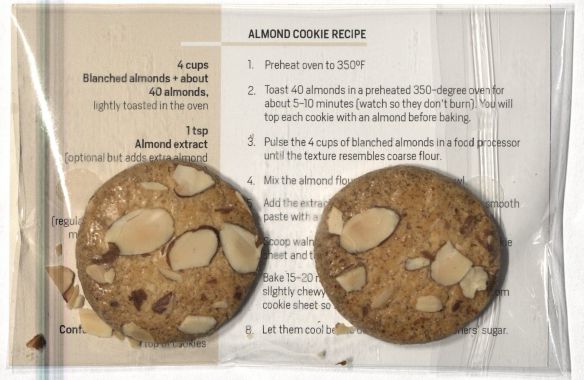

Many books also contain lists of foods the nursing mother should and should not eat. Dr. Anne Newton, in her Mother and Baby: Helpful Suggestions Concerning Motherhood and the Care of Children (1912), advises mothers to practice “sacrifice and self-denial” in eating meals, and to avoid rich and seasoned foods altogether.7 Newton specifies that mothers should eat “nothing about which there is any question of fermentation. Such vegetables as cabbage, turnips, cauliflower, and tomatoes should not be given until the baby is four months old at least, and even then certain things may cause discomfort and cannot be indulged until the child is weaned.8” Dr. Thomas Gray, in Common Sense and the Baby: A Book for Mothers, notes that the breastfeeding mother should “eat an abundance of wholesome, nutritious food; avoid indigestible pastries and salads. Take sparingly of tea and coffee. Drink freely cocoa and milk. Eat fruits – not acid.9” Some more recent books are much less rigid about the mother’s diet. Dr. Dorothy Whipple, writing in 1944, is less cautious, and argues that there’s very little a mother can eat that harms a nursing baby, mentioning only certain foods like onions that may, in breast milk, deter babies with its “unusual taste.10”

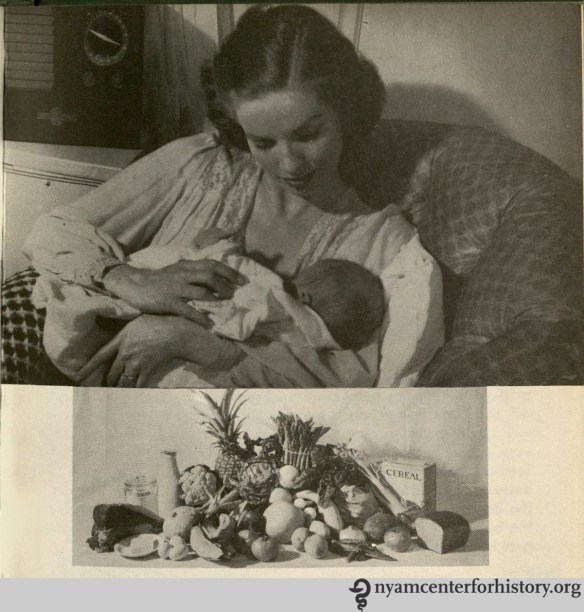

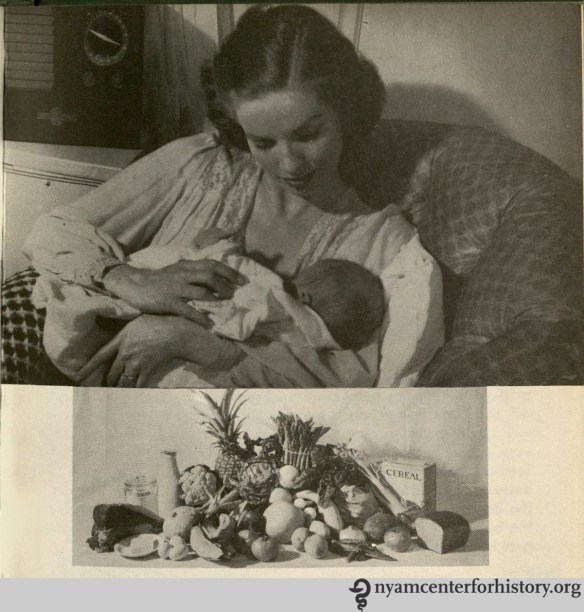

A mother breastfeeding and a selection of foods recommended for the breastfeeding mother, taken from Stella B. Applebaum’s Baby: A Mother’s Manual (1946).

Front cover of the New York City Health Department’s The Care of Baby, 1932.

None of the books I consulted recommended breastfeeding to two years or beyond, the WHO’s current recommendation on breastfeeding. Most books recommend weaning the baby between eight and fourteen months of age. The New York City Department of Health warns against weaning in summer because of the risk of spoiled cow’s milk:

If possible, do not wean your baby during the hot summer months…. If you are well, it will not harm you to nurse your child until the dangerous, hot weather is over. This precaution may mean saving your child’s life.”11

“One of life’s richest experiences,” from Dorothy Whipple’s Our American Babies, published in 1944.

Another common thread in the literature about breastfeeding is an emphasis on the pleasure and health benefits experienced by the nursing mother. According to Tucker, “under the right conditions of lactation, … the mother should thrive and even grow stout.12” Others emphasize that breastfeeding will help the mother “get her ‘good figure’ back much more quickly than the mother who doesn’t nurse” because “nursing causes the uterus or womb to contract.13” Stella Applebaum provides this summary of the mother-baby nursing relationship:

Mother’s milk is the perfect baby food. From a healthy mother’s clean nipples, this pure, fresh, warm, nourishing, digestible food is delivered, germ-free, directly into the baby’s mouth. At the same time mother’s milk protects him against certain diseases. Suckling at the breast makes the baby feel close to his mother, happy, and secure.

Nursing benefits you, too. It stimulates the uterus to contract to normal size and contributes to your personal enjoyment and contentment. Propped in a comfortable chair or bed, you share a uniquely satisfying experience with your baby.14

Other writers underscore the vital role nursing plays in strengthening the emotional bonds between mother and child. Buchan writes in 1804 that “the act itself is attended with sweet, thrilling, and delightful sensations of which those only who have felt them can form any idea.15” Dorothy Whipple has the last word:

…to sit in a comfortable chair and hold a little snuggling baby in your arms, to watch him grab that nipple with all the fury of his tiny might and suck and work away until he reaches that complete satisfaction that comes to a baby with a full stomach is one of the pleasantest sensations in life.16

References

1. Buchan, William. Advice to Mothers, on the Subject of Their Own Health; and on the Means of Promoting the Health, Strength, and Beauty, of Their Offspring. Philadelphia: John Bioren, 1804, p. 75-76.

2-3. Tucker, Genevieve. Mother, Baby, and Nursery: A Manual for Mothers. Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1896, p. 85-87.

4. Kerley, Chalres Gilmore. Short Talks with Young Mothers: On the Management of Infants and Young Children. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904, p. 13-15.

5. Eldred, Myrtle M. For the Young Mother. Chicago: The Reilly & Lee Co., 1921, p. 37.

6. Kenyon, Josephine Hemenway. Healthy Babies Are Happy Babies: A Complete Handbook for Modern Mothers. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1934, p. 55-56; Zabriskie, Louise. Mother and Baby Care In Pictures. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1941, p. 131.

7. Newton, Anne B. Mother and Baby: Helpful Suggestions Concerning Motherhood and the Care of Children. Boston: Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Co., 1912, p. 74.

8. Ibid., p. 78.

9. Gray, Thomas N. Common Sense and the Baby: A Book for Mothers. New York: the Bewick Press, 1907, p. 39.

10. Whipple, Dorothy V. Our American Babies: The Art of Baby Care. New York: M. Barrows and Company, Inc., 1944, p. 139.

11. New York City Department of Health. The Care of Baby. New York: Department of Health, 1932, p. 10.

12. Tucker, p. 86.

13. NYC Dept. of Health. The Care of Baby, p. 5.

14. Applebaum, Stella B. Baby: A Mother’s Manual. Chicago and New York: Ziff-Davis Publishing Company, 1946.

15. Buchan, p. 79.

16. Whipple, p. 122.