Registration is now open for our hands-on art and anatomy workshops, presented as part of our Vesalius 500 celebrations on October 18, 2014. Create your own articulated anatomical figure or “exquisite corpse” at the Gladys Brooks Book & Paper Conservation Laboratory; learn Renaissance drawing techniques with medical illustrator Marie Dauenheimer; or explore the anatomy and art of the hand with physical anthropologist Sam Dunlap.

Spaces are strictly limited so register soon. Registration at one of the workshops includes free entry to the Festival. You can register for the Festival (without workshop attendance) here.

From the Cradle to the Grave: Session One: The Cradle

Moveable baby and female pelvis from one of NYAM’s 19th century obstetrics texts, Dr. K. Shibata’s Geburtschülfliche Taschen-Phantom (Obstetrical Pocket-Phantom).

Working with NYAM’s conservation team, celebrate Vesalius’s life with a hands-on workshop producing your own articulated anatomical figures in the Gladys Brooks Book & Paper Conservation Laboratory.

Time: 11am-1pm

Cost: $55

Includes: All materials, and free entry to the Festival.

Maximum participants: 12

Register here

During the morning’s Cradle workshop, we will construct paper facsimiles of a moveable baby and female pelvis from one of NYAM’s 19th century obstetrics texts, Geburtschülfliche Taschen-Phantom (or the Obstetrical Pocket-Phantom). The book was written by Dr. K. Shibata, a Japanese author studying in Germany, and was published first in German before being translated into English and Japanese.

Participants will have time to make at least one paper baby and pelvis, which can be produced as paper dolls or magnets.

From the Cradle to the Grave: Session Two: The Grave

Working with our conservation team, celebrate Vesalius’s life with a hands-on workshop producing your own “exquisite corpse” in the Gladys Brooks Book & Paper Conservation Laboratory.

Time: 2:30pm-4:30pm

Cost: $55

Includes: All materials, and free entry to the Festival.

Maximum participants: 12

Register here

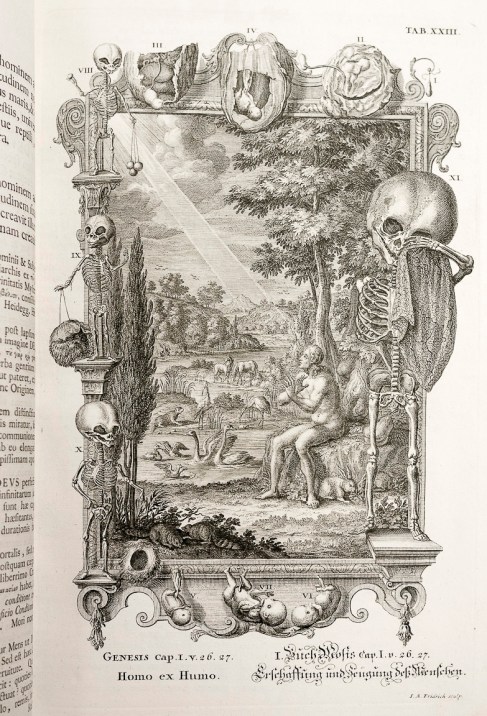

During the afternoon’s Grave workshop, we focus on producing a Vesalian-themed exquisite (or rotating) corpse. Loosely based on the surrealist parlor game in which a picture was collectively created by assembling unrelated images, this workshop will employ a special, rotating binding structure and mix-matched facsimile images from NYAM’s rare book collections to allow students to create their own unique, moveable pieces of art.

Renaissance Illustration Techniques Workshop with Marie Dauenheimer, Medical Illustrator

Time: 10am-1pm

Cost: $85

Includes: All materials, and free entry to the Festival.

Maximum participants: 15

Register here

Artists and anatomists passionate about unlocking the mysteries of the human body drove anatomical investigation during the Renaissance. Anatomical illustrations of startling power vividly described and represented the inner workings of the human form. Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks were among the most magnificent, merging scientific investigation and beautifully observed drawing.

Students will have the opportunity to learn and apply the techniques used by Renaissance artists to illustrate anatomical specimens. Using dip and technical pens, various inks and prepared paper students will investigate, discover, and draw osteology, models, and dissected specimens from various views creating an anatomical plate.

Understanding the Hand, physical anthropology workshop with Sam Dunlap, Ph.D.

Time: 2:30pm-5:30pm

Cost: $75

Includes: All materials, and free entry to the Festival.

Maximum participants: 15

Register here

The hand as an expression of the mind and personality is second only to the face in the Renaissance tradition of dissection and illustration that continues to inform both art and science. Basic anatomical dissection, illustration, and knowledge continue to be fundamental in many fields from evolutionary biology to surgery, medical training, and forensic science. This workshop will offer participants the opportunity to explore the human hand and its anatomy, which will be demonstrated with at least three dissections. Opossum (Didelphis virginiana) and orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) forelimbs will be available along with other comparative skeletal material. We will discuss hand evolution, embryology, and anatomy, and the artistic importance of the hand since its appearance in the upper palaeolithic cave art. We will also analyze the hand illustrations of da Vinci, Vesalius, Rembrandt, and artists up to and including the abstract expressionists.